by Björn Schöpe

translated by Annika Backe

April 23, 2015 – No matter how you think about Google you simply cannot ignore this digital giant’s range of offers which not only scores with quantity but also with quality most of the time. Admittedly, Google is not yet firmly-established when it comes to art and education but the company definitely has a foot in the door: the project is called Google Cultural Institute.

Collections, museums and institutions are given the chance to make their material accessible online. Everybody may browse, at any time and at any place, without the need to sign in. The sheer number of “exhibitions”, as it is already, is as impressive as rich.

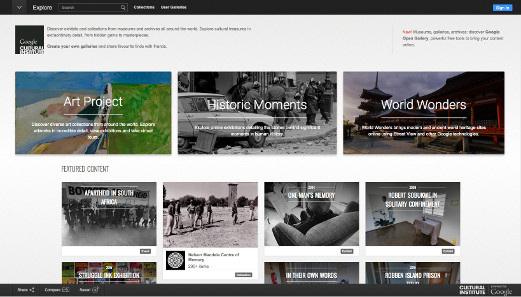

On the one end of the scale there are exhibitions that look more like a PR campaign with the charm of a glossy print. A case in point is the exhibition ‘Made in Italy’, presenting specialties from regional Italian cuisines in a way that wets one’s appetite, providing nice images and only little accompanying text.

This exhibition’s gallery of handcrafts, however, rather looks like a company museum. The viewer is provided with information about the history of the hat manufacturer Biella, for instance.

In the category ‘World Wonders’ one browses through a compilation of important monuments of the earth, the Giza pyramids complex, Angkor Wat, Taj Mahal. Many of the images come in a very high resolution, enabling the viewer to magnify even the tiniest detail on postcards or photographs and look at it in full-screen view.

It is impressive to see what the Kunsthistorisches Museum Vienna makes of such a possibility in respect of a small-scale object: the viewer can look at a portrait of Augustus from all angles and from up close.

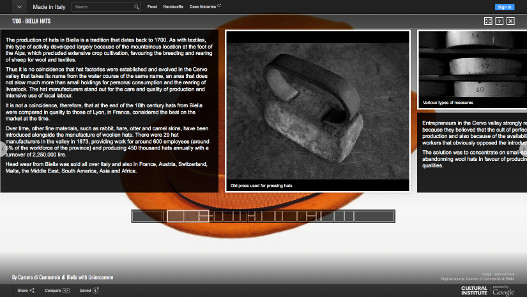

Unfortunately, some objects offer little more information than the mere picture. Yet there are nice ‘educational bits’ available as well. The National Portrait Gallery of Canberra, for example, presents the portrait of the explorer James Cook and elaborates on a ‘hidden message’.

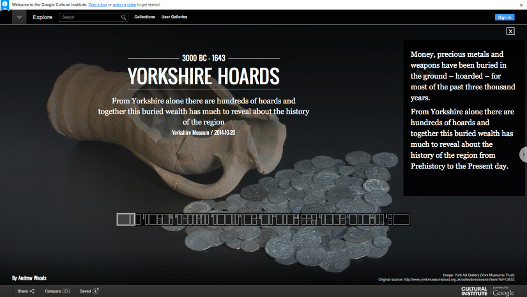

Many numismatists will find interesting exhibitions, too. Yorkshire Museums Trust in Northern England, for instance, shows an exhibition of hoards. Unlike the museum, the internet makes it possible to present numerous hoards from the Northern part of England spanning a chronological range from 3000 B. C. to the 17th century by means of superb photographs. Informative texts as well as short movies with the curator commenting on objects complete the images.

Google Cultural Institute is only as good as its uploaded contents. Quality can vary, and the range is huge. Time will tell how this project evolves and whether or not it has a lasting effect. It has great potential, though, and everyone can discover and learn many things in that virtual realm already. In the future, museums will give this option more thought in order to overcome existing limits, in terms of space or financial means. Ideally, cultural institutions distribute their range of offers throughout the whole world that way and attract people to the museum. There, they come in close contact with “the real thing”, offline, and “perceive” and “experience” it first-hand. And that is something no illustration on the internet can compete with.