In 1755 an earthquake shook the city of Lisbon for almost six minutes. And on All Saints’ of all days. The earth split open in the very city centre. All of the churches and many palaces were swallowed by gaping chasms in the earth or burned down in the subsequent fire. Those who survived the earthquake drowned in the devastating tsunami which hit the city after the earthquake.

While the king set shaking in his tent – until the day he died he would never lose his fear of closed spaces again, the Marquess of Pombal organised the rebuilding of the city. His words speak of pragmatism: “What now? Bury the dead and feed the living.” His architectural measures shape the city until this day and on our walks in Lisbon we will see traces of the Marquess more than once.

The Lisbon earthquake caused heated debates among philosophers across Europe about the question how an omnipotent and omnibenevolent God could have allowed for this disaster to happen. Why had the earthquake hit on All Saints’ Day of all days? Why had the red-light district been spared and the churches destroyed?

Voltaire had once more proved himself to be a pretty obnoxious fellow and gotten himself personally kicked out of Berlin by Frederick II for his latest intrigue. To him the earthquake was the reason to write a deeply pessimistic satiric novella in which he confronts his naïve hero Candide with all the evils of his time, among them the Lisbon earthquake.

Even at old age, Goethe still remembered the impression the earthquake had made on him as a six-year-old boy, when he wrote in 1811: “The boy, who absorbed all this, experienced no little bewilderment. God, the Creator and Sustainer of heaven and hearth, whom the First Article of Faith had portrayed as so wise and merciful, had allowed the just to suffer the same as the unjust, thus in no way proving to be fatherly.” (Peter Boerner, “Goethe,” transl. by Nancy Boerner. Haus Publishing, 2015.)

Easter Sunday, 4 April 2015

To be honest, we were kind of grateful to the earthquake because it gave the city the broad “avenidas” from the reconstruction period under Marquess of Pombal, which were considerably easier to move around in than the older, narrow alleyways packed with too many tourists. Lisbon is famous for its pickpockets, who, according to the locals, only rob people who do not speak Portuguese perfectly … So we tried to avoid the older districts and stayed on the axis Avenida da Libertade – Rossio – Praca do Comercio.

When you see that the place that once was home to the inquisition and the auto-da-fés is now a gigantic empty space, it makes you wonder if perhaps God knew exactly where he was sending his earthquake. The space has since then been used for Lisbon’s great market as well as for the popular bull fights.

Rossio Square offers a good view of the Carmo church ruins, once the most important Gothic church in Lisbon. It collapsed during the earthquake. The ruins have remained in place as a memorial.

Between Rossio and Praca do Comercio lies the Baixa, the district of merchants and artisans that was rebuilt after the earthquake. Baixa simply means “lower”, which explains the district’s alternative name Pombaline Lower Town, and in a city like Lisbon we appreciated not having to run up and down stairs for once. If, however, you should wish to see the Bairro Alto (the upper district), you will have to either walk up by foot (and lose your breath), take the tram (beware of pickpockets!) or take one of the lifts (even more pickpockets!!), whose sight is day and night accompanied by long waiting lines. In Bairro Alto you will find lots and lots of little restaurants and even more shops where countless tourists buy all those things whose attraction becomes inexplicable even for them once they have returned home.

The city’s gate to the world is the Praca do Commercio on the riverbank of the Tagus. Here you can see ships pass by and, with a little imagination, picture that they are sailing out into the wide, wide world. The statue of Joseph I of Portugal, the unlucky king into whose reign the earthquake fell, is watching above all this. The memorial commemorates Joseph’s contributions to the rebuilding of the city, which, to be honest, probably consisted mainly in not disturbing the Marquess of Pombal’s work.

The Marquess, by the way, was honoured elsewhere. Some 100 years later the city built a triumphal arch that opens up to the Praca do Comercio. It depicts Pombal and Vasco da Gama as equals.

The Nacional Azulejo Museum is a great place to go if you are interested in what Lisbon looked like in the past. The former Convent of Madre Deus holds a figurative panel of Lisbon before the earthquake. Finding the museum is not easy. You have to get on the right bus and off the right stop. Personally, I like those museums which are more difficult to find (and, if possible, not starred in the Baedeker). They have the advantage of never being completely overcrowded, not even on Easter weekend. So we decided to spend Easter Saturday there.

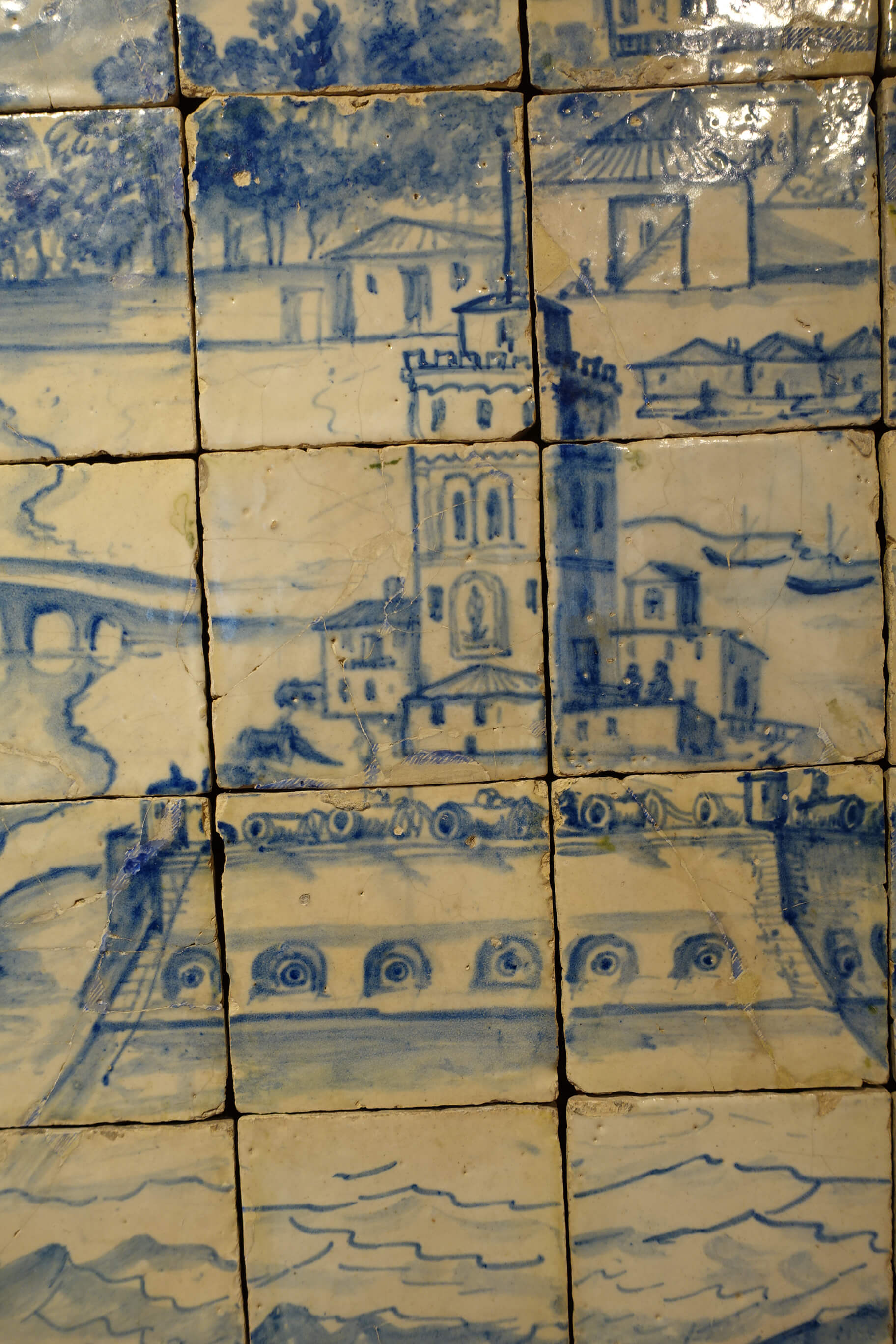

And, as expected, we spent the 20 minutes waiting time at the bus stop with only three other tourists. The locals are used to insecure tourists. When we looked around searchingly and were about to miss our stop, they energetically kicked us out just in time. We almost did not find the museum. It just looks so inconspicuous from the outside. The more precious are its treasures inside. The museum’s highlight is the several meters long tile display Great View of Lisbon which shows the city before the earthquake.

It not only shows important buildings like the Torre de Belem or the royal palace, which after the earthquake had completely disappeared but also the old customs facilities and granary and the market in the Ribeira district.

A small technical wonder is this depiction of a tide mill which uses tidal rise and fall to drive its grind works. Such tide mills have been around since the Middle Ages, predominantly on Atlantic coasts where the tidal range is powerful enough to drive the grinding works.

Azuleijo comes from Arabic. Al zulaji simply means “small polished stone”.

What started out as colourful, durable paintings used to decorate ecclesiastical architecture (tiles were more durable and low-maintenance than any other kind of textile or fresco), soon came to decorate private houses.

Of course this medium is ideal to tell stories, such as that of young António Joaquim Carneiro, a farmer’s son who did not like the work on the farm.

When he came to the city, he decided to learn the hatter’s trade. He was successful. His shop was well-frequented and he sold to the most select circles.

Carneiro’s hats became so popular that he had to build a factory to meet the demand. With the tiles the hatter immortalised himself and his story in a form of 18th century comic. Even those who do not speak Portuguese will immediately understand this short story from the industrialisation period told by the images.

After a sumptuous meal in the cloister of the former convent, which today serves as an (excellent) restaurant, we wanted to return to our hotel. Which turned out to be more difficult than anticipated. We seemed to be standing in the wrong place somehow. Almost one hour passed and still no bus going in the right direction. But what do we have common sense for? If the bus drives in one direction, it must return the other one eventually, right?

So why not use our day pass to get on and take a round trip. No sooner thought than done. And then we were driving through suburbs of Lisbon, which looked anything than usual, for almost an hour. When we finally arrived at Estacao do Oriente, arguably the most important transport hub in Lisbon, the bus driver kicked us out with the comment that he finished work now. We could have once more waited forever for the next bus to come. Or we could take the metro – and that we did.

Lucky for us we made that decision because that way we got to see the modern sequel of our trip into the land of painted tiles. Orient metro station is a kind of tile museum in its very own way. It displays tile art by known and unknown artists.

We missed not one but several trains until we had finally admired and photographed all colourful images in the way the deserved. And that was another eventful day come to an end.

The tourists were still as numerous as before. Nevertheless, we will jump right into medieval Lisbon in the next episode before we take leave of this pulsating metropolis and make our way east.

Here you will find all episodes of our series “Global Power Portugal”.