The interview was conducted by Ursula Kampmann

UK: Can you recall the moment you first realized that coins were something fascinating?

Bernd Kluge in his office, talking to Ursula Kampmann.

BK: To be honest, I only realized it when I was already employed at the Münzkabinett. Working with coins was nothing that ran in the family. Coins only became an issue to me when I tried to find a suitable job in the medieval area once I finished my studies of history at the Humboldt University Berlin. The only vacation available was at the Münzkabinett. I then came here on a trial basis, and, strictly speaking, not so much the coins made the difference but the beautiful rooms, the large doors, the library, in short the entire classy and academic atmosphere. Well, I said to myself, let’s just try this numismatics for once. That it was to become something for life was not yet apparent at the time.

UK: Can you remember your very first day at work?

Arthur Suhle, Director of the Berlin Münzkabinett 1898-1973. From B. Kluge, Das Münzkabinett, 2nd ed., Berlin 2005, p. 27.

BK: I remember it vividly. The date was 1 October, 1972. My dear colleague Lore Börner, who won me over to numismatics in the first place, led me to the ‘Great Treasure Vault’, our central collection depot. Back then, all academic researchers were sitting in the room as if it were some kind of open plan office. Everybody had his own desk cubicle. She led me into one of the cubicles and said: “This is your place, this is where Professor Suhle used to sit. I have already cleared one of the drawers for you.” In this drawer I then put the few things I had brought with me. The next day my self-training as a numismatist began. The first thing I learned was that a groschen was a 1/24 thaler. Since I had studied library science as a second subject, one of my first tasks was to re-organize the library, the offprints in particular. This way, I got an overview rather quickly and became acquainted to the most important names. After one year I already knew a thing or two, and after three years I submitted my first numismatic publication. (the publication was: Brakteaten. Deutsche Münzen des Hochmittelalters, Berlin 1976 [Kleine Schriften des Münzkabinetts, vol. 2]; author’s note.).

UK: Who were your colleagues back then?

BK: The director still was Arthur Suhle, at least formally. However, he was already high in his seventies and his health prevented him from performing any permanent duty. He came to the Cabinet once a week and checked on things, let himself be entertained and took a cab to go home afterwards. As a matter of fact, he did not conduct the Cabinet’s affairs anymore – that was Lore Börner’s job as his representative. As for the scientific areas: she was responsible for the medals and the coins of modern times. The antiquity’s department was overseen by the couple Hans-Dietrich and Sabine Schultz. My humble self was to take over the Middle Ages and, apart from that, taking a bit of the burden from Lore Börner in regard to modern times. A year later, Hermann Simon joined the team, and he was responsible for the Oriental coins. Apart from these five academic researchers, there were two conservators and a secretary.

UK: What did your work entail exactly? Did you first unpack the coins that had returned from Russia?

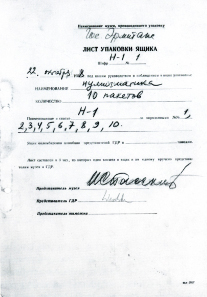

Lists from the Soviet handover reports on the returning of the coins and medals 1958. From B. Kluge, Das Münzkabinett, 2nd ed., Berlin 2005, p. 29.

BK: The unpacking had long been done by then. What awaited us – and me, as I arrived right in the middle of it – was the toil of a general revision of the collections that had been returned from the Soviet Union in 1958. When the coin trays were being put into the drawers again it became apparent that all trays were present and accounted for but that every single one of them was in disarray. What followed then was a revision of the stock from A to Z, conducted with military precision, insofar as we systematically checked, in every cupboard and in every tray from end to end, if every single coin was lying on the right piece of paper with the correct statement of provenance. We literally examined piece after piece, which took us more than 20 years, while the challenge was to join the right coin with the right piece of paper.

UK: Had the trays been dropped in Russia?

BK: No, certainly not. The entire collection had been evacuated form the Kaiser Friedrich Museum (today Bode Museum) to the air raid shelter in the Pergamon Museum in 1942. The trays had already been bundled and tied up to form larger packages for transportation. In these packages the collection was then transported by the Red Army to St. Petersburg, which of course was called Leningrad back then, by train in 1945. Probably in order to count the coins and to do some statistical work, they were removed from the trays, but only the gold and the silver coins, to be specific. Copper and bronze were left untouched. The mess was created when the Russian noble metal counters actually turned the trays when they put the coins back in. Our trays are lying in an upright position, but the Russians had made it a landscape format to the effect that there are still the right coins on the tray, albeit the pockets they were lying in were completely wrong. To find the key to this systematic disarray and to put the coins back in the right order was the detective work of those years.

UK: Who was the first one to realize how it worked?

BK: The colleagues from ancient times were the first ones to notice. As for modern times, the situation was not that sincere because on most of the coins the date is given. These dates are likewise stated on the little sheets of paper, so that it was relatively simple to join the coins dating from 1768 with the cards stating the year 1768. As for ancient and medieval times, hardly any coin comes with a year. In some cases, it took a lot of provenance research to combine the right coin and the right card again. For example, the recording of the findspot is extremely important in the case of medieval coins, in order to resolve questions as to where and when the often silent coins had been produced, as can be seen with the bracteates. Sometimes the task was such a difficult one that we had to spend an entire day on one single tray.

UK: In what way was the Münzkabinett incorporated into the Museum Island? Or, to better rephrase the question: who acquired what material, to be put on display when and where?

The great treasure vault, around 1975, back then the permanent working place of the academic researchers. From B. Kluge, Das Münzkabinett, 2nd ed., Berlin 2005, p. 28.

BK: Like the Antikensammlung, the Gemäldegalerie, the Kupferstichkabinett or the Museum für Vor- und Frühgeschichte, the Münzkabinett was one of 13 museums of the ‘Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Hauptstadt der DDR’ (as the official title read). When it came to issues like what exhibition to make, what purchase to make or what publication, it was left to the museums to decide.

UK: You just mentioned purchases. Was it that easy to purchase in the times of the GDR?

BK: There was no foreign currency, i.e. hard currency, to purchase on the international market. But we possessed enough money for the national GDR market. Often, we were not even able to spend all the money available to us because there was not enough material on offer. The GDR market simply did not have enough in stock. Hence, we bought primarily modern coins and medals. We were not able to acquire many ancient and medieval coins, for the simple reason that the range of offers of the State Art Trade was likewise very limited. Considerably more we purchased from private persons. More important than buying, however, was exchanging. Private collectors were reluctant to sell their coins. They were not so much interested in the GDR money. When they divested themselves of something they wanted to get something in return.

UK: That did not pose any problem? You were free to choose which doublet you wanted to exchange?

BK: Yes, we were. Since our collection had been transported to the Soviet Union in 1945 and nobody was able to anticipate if it would be returned at all, Arthur Suhle tried to fill the dismally empty cupboards somehow. He did his best to gather anything available in the country, including loans but a lot of acquisitions as well. The loans from museums were returned after 1958 because the regular collection had come back, but the coins that had been purchased between 1945 and 1958 – which comprised a great many (c. 22,000 pieces, author’s note) – of course stayed. The items the collection was lacking were incorporated. But there was much left that did not fit in the collection because it was already there or in no museum-like condition. The result was a large stock of doublets which we made good use of when we wanted to exchange material with private collectors. By the way, the greater part of these doublets was realized as late as 1993, after the Turnaround, in order to finance the most significant acquisition since 1945, the purchase of the Stefan Collection of coins dating from the Migration Period.

UK: What did the exchange entail exactly?

BK: Well, it was a real haggling sometimes. The collectors always pursued their interests, but naturally we did not want to bring in second-best material at inflated prices. I remember one incident that happened at a time when I had just started working at the Cabinet. The Berlin correspondent of the Pravda, the then biggest daily newspaper in the Soviet Union, visited the Münzkabinett and was interested in German thaler. He, on the other hand, had brought reels of Russian roubles with him. That started the rouble rolling: I exchanged roubel for thaler with him and hence enriched the collection by a vast amount of roubel from Peter I to Nicholas II.

UK: Considering the current Russia boom that indeed was a bargain.

BK: Back then, roubel were no big deal. And that was only one example of such an exchange action on a larger scale. The true, the big collectors, which the GDR had a couple of, too, positively knew what they wanted from us in return. When it came to Brandenburg-Prussia, things could get tricky. You see, we often lacked just the first-class material in that department.

Admittedly, we also acquired on the art market. Albeit, generally speaking, there was nothing available from the A-list, because most of it had already been sold to the west. But there were exceptions from time to time.

UK: And how did the state coin trade work? Were there any auction sales conducted?

BK: In the GDR era, auction sales were major events. They were often conducted in huge halls that were filled to capacity.

UK: How many people did attend?

BK: I would guess 500 or 1,000 at times. Most of them did not actually buy. They only made notes about the prices. That was the only opportunity to get information about the market. After all, we did have any access to catalogs from the west or coin price guides. We derived our asking prices from observing the market. That was why the auctions became the important venue. Of course, the collectors used to exchange their material outside the auction hall. Everyone came with his albums, and then there were all kinds of selling and buying going on. That was not permitted officially, but nobody really cared.

Part 2 of the interview you can read here. Then, Bernd Kluge tells us how KoKo operated, and how the Münzkabinett, after the Turnaround, secured the legacies of Alexander Schalck-Golodkowski for numismatics.