The interview was conducted by Ursula Kampmann

Translation: honeycutshome

October 16, 2014 – In 2009, Bernd Kluge, Director of the Münzkabinett (Coin Cabinet) of the Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, gave Ursula Kampmann an interview and explained to her what it meant to work in the Münzkabinett in the GDR era and to lead it through the Turnaround and the German Reunification. On the occasion of his retirement on 1 October, 2014, we publish this interview again in CoinsWeekly.

UK: And how about the coins that were acquired to be exported to the west?

BK: Every time there was a buyer of the ‘Außenhandelsimperiums der DDR’, which Alexander Schalck-Golodkowski was the head of, sitting in the auction hall. The official title was ‘Kommerzielle Koordinierung’, nicknamed Ko-Ko by the people. It was always this Mr. M. and he was sitting in the first row. He raised his panel only slightly. Nobody in the room actually saw him bidding except for the auctioneer who of course noticed, and everybody knew. And the price went higher and higher.

We cut KoKo short a couple of times. The GDR had a law on the protection of cultural property which likewise KoKo was bound to. When we invoked that law, they could buy the coin but they were forbidden to export it afterwards. That of course rendered the coin worthless. Then came Mr. M. and said: “Well, you can get the coin all right but I want something of equal value in return.” It goes without saying that we did not want to comply because he would have sold everything we provided him with to the West immediately. I still remember a beautiful gold coin, a unique specimen from the Bishopric of Hildesheim dating from the 17th century. KoKo was stuck with it since we had imposed our ban on it. Eventually, we were able to buy it but cost us 7,000 mark or so. Back in the GDR, that was a lot of money.

UK: How did the collectors react to Schalck-Golodkowski?

BK: Naturally, they choked back their anger. What else. We were not aware of the fact that a Mr. Schalck-Golodkowski was behind it. That grey eminence never appeared in person. We only knew this certain Mr. M. and knew that he bought for the export – which made him a hated person at the auction sales. He just lifted his bidding card and thus killed everyone else. On the other hand, he did not have a pre-emption right and had to win out over the competitors in the room. But since he knew what he would get for the coin in the West, he could purchase most of the specimens without any problems.

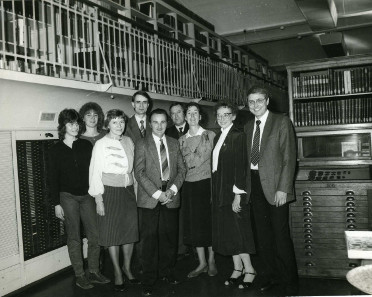

A part of the Münzkabinett staff present at the retirement of Dr Lore Börner in 1988. From right to left: Wolfgang Steguweit, Lore Börner, Sabine Schultz, Hans-Dietrich Schultz, Günther Schade (Director General), Bernd Kluge, Gisela Stutzbach, Manuela Stolzenberger, Eva Frommhagen. Photo: Münzkabinett archive.

UK: I have read somewhere that Wolfgang Steguweit managed to secure the stocks of KoKo for the museums after the Turnaround. Can you elaborate on that?

BK: That really was an exciting story. The Turnaround made things possible that were unheard of before, including the angry people overthrowing the empire of Schalck-Golodkowski. Art was a mere appendix that was concentrated at Mühlenbeck not far from Berlin. The last Culture Secretary, Dietmar Keller, brought a commission into being with the purpose to somehow deal with the liquidation of the works of art piled up at Mühlenbeck. Steguweit was appointed member of this committee. In this function, he visited the depot in Mühlenbeck. There, he realized that there were several thousands of coins, medals and banknotes amongst the works of art as well. Steguweit of course said that we had to secure the things of value for the museums under all circumstances. And when a price tag was attached to the whole, the sum added up to about 1.5 million, modestly estimated. That sum was provided by the last government of the GDR.

UK: East or West German money?

BK: East German money, all East German money. Then the items came to our house. We have distributed them: to the coin cabinets in Dresden, Gotha, Halle, Schwerin, Weimar, and Magdeburg. The material relevant for Berlin stayed here at our Münzkabinett. We have left the material as a conglomerate as testimony to the Turnaround and the cultural holdings of the GDR, and we have made an inventory of it. The material makes half a cupboard, and we call it the Mühlenbeck Collection.

UK: Talking about Wolfgang Steguweit: the two of are more than mere colleagues, you are friends. How and when did you become acquainted to him?

BK: I remember quite well, actually. We met in Prague, in October 1974, during a symposium that was organized by the Czech Numismatic Society. Guests from abroad were invited, too, from the GDR but likewise from the FRG and from Switzerland. It was my very first foreign trip and, by the way, my first flight, too. We started at Berlin, destination Prague. Steguweit and I, we made the youth group of this meeting, amongst all the distinguished ladies and gentlemen of an advanced age, in fact it was nothing different from today numismatists. At that time, Steguweit was shortly before his 30s and I was not yet 25. We were quite young back then indeed.

UK: You have urged him to come to Berlin?

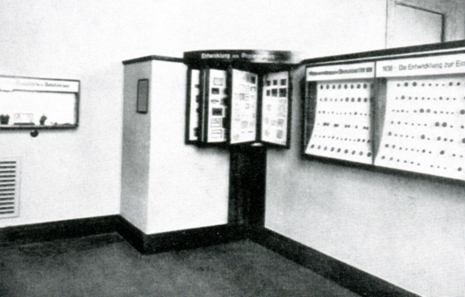

View inside the exhibition of the Münzkabinett at the Bode-Museum, 1956. From B. Kluge, Das Münzkabinett, 2nd ed., Berlin 2005, p. 38.

BK: Yes, he coming to Berlin is partly due to me. He had awaken the Münzkabinett Gotha from its slumber and started on a new display of the collection and to make a new inventory. Slowly but steadily, however, he reached certain limits that were hard to overcome in the province, harder than in Berlin. Many of his superiors were Party officials to the bone. In Berlin, things were bit more focused on the academic work and more liberal-minded. Besides, we wanted to mount something together.

Upon his arrival, he had to assume the office of director at once, after Heinz Fengler (Director of the Münzkabinett from 1973 until 1988, author’s note) had retired. Strictly speaking, that was not something he wanted to do. He always saw himself as a man of the second row. The Director General, however, was impressed by Steguweit’s exhibitions at Gotha, and he wanted to see the Münzkabinett more present at the Bode Museum in regard to exhibitions. That had not been achieved under Fengler or was limited to smaller special exhibitions only and a permanent exhibition in the Pergamon Museum, respectively. And that was where Steguweit came in.

UK: Wolfgang Steguweit did not stay director for very long, though.

BK: Steguweit always thought that it would be my job, because I had been here much longer and had published quite a lot. And when he saw his chance after the Turnaround to influence things according to his interests he just did. Admittedly, I was a bit alienated when he came to me one morning and, without any prior warning, expressed his intention of receding from the director’s office. He had done a very good job and I saw absolutely no reason for him to step back. Well, Steguweit is and never was a ‘Lafontaine’ and thus navigated the cabinet ship through more than one severe weather and dealt with the turmoil of those times. The Münzkabinett was on a good way, and under his aegis I, as his representative, had the chance to mainly focus on my academic projects.

UK: The two of you managed to change internally without facing any major problems?

BK: Things of course weren’t that easy. Back then, we were already under the auspices of the Stiftung Preußischer Kulturbesitz (Prussian Cultural Heritage Foundation), and it was left to the President of the Stiftung and the Director General to decide. The latter was Wolf-Dieter Dube. Dube had a high self-esteem, with clear expectations, and he was no one to be easily persuaded. Together with the President of the Stiftung, Werner Knopp – who was a lawyer, diplomat and old-school gentleman, who used to be President of the Rectors’ Conference of the (Western) German universities – oversaw the entire unification of the Staatliche Museen (State Museums), the Staatsbibliotheken (State Libraries) and the Preußische Staatsarchiv (Prussian State Archive). He had no interest in generating any additional trouble, apart from the one he already had to deal with, because of the East directors being reduced in rank and becoming merely deputies. Thus, he asked his colleagues in the West: “Do you know of someone that, numismatically speaking, has the same standing as Kluge in (East) Berlin?” And apparently they informed him that there weren’t so many numismatists available in the FRG with a much better qualification. Under these circumstances and because the then pressing tasks called for a quick solution, the director’s vacancy was advertised internally, inside the Stiftung, only. I applied, too, although I didn’t really want the job, but I couldn’t back down and it goes without saying that I didn’t want to be faced with one of the then numerous imports from the West.

UK: I find that unbelievable. Today, everybody intends to climb up the greasy pole as high as possible. Why did you think different?

BK: In the GDR, many people were working at the museums who more or less had waived the chance of a career. Because they were no party members. Because they had no intention of joining that nonsense with party meetings and declarations of loyalty. Because they wanted to be left alone and pursue their academic work. The Münzkabinett was the ideal place for that. Needless to say that only the party membership book would get you a leading position, or was very helpful at least. That was why I didn’t look for a leading position. It was always clear to me: party membership book, no way. Admittedly, we had some museum directors that were no member of any party or no member of the SED (Socialist Unity Party of Germany) but of one of the so-called bloc parties, respectively.

UK: And that was the reason for you to leave the university?

BK: Yes, that was the sole reason. I would have loved to stay at the university, and my supervising professor, Bernhard Töpfer, who by the way was no party member either, would have loved to keep me. But he didn’t see any chance to get someone a job at university that wasn’t a member of the party and didn’t even properly engage in the FDJ (Free Germany Youth). And I didn’t want to make too many political compromises, on the other hand. In short, I had somewhat put any chance of making a career behind me when I started working at the museum, I concentrated entirely on my research and, as a matter of fact, I have achieved quite a lot in this department over the course of 20 years.

Here you find Part 1 of the interview.