For more than half a century, the popes had been resentful of the existence of a secular Italian state and spent their time sulking in the Vatican. However, in 1922 Pius XI (1922-1936) was elected, finally a pope who was willing to intervene in politics. Concordats – international agreements between the Catholic Church and a state – were to regulate the relationship between the Church and the European countries.

The Reconciliation Between the Vatican and Italy

In 1929, such a concordat – the so-called Lateran Treaty – put an end to the 60-year feud between the Italian state and the Vatican: The Pope recognized the Kingdom of Italy with Rome as its capital. Thus, for the first time since the state had been founded, Italian Catholics were officially allowed to engage in Italy’s political life. In return, the Pope obtained his own state – the Vatican State, which covers barely one square kilometre in size – and, as compensation for the lost Papal States, the enormous sum of one billion lire as state bonds and 750 million lire in cash. This means that the starting capital of the smallest state in the world amounted to the equivalent of about 80 million dollars.

Mussolini and Hitler: Contracting Parties of the Pope

By means of a reconciliation with the Pope, Mussolini healed old wounds. In deeply Catholic Italy, this treaty conferred a lot of prestige to the Duce – just as the concordat with Hitler’s Germany was to increase the prestige of the Nazis a few years later. Although Pius XI did neither appreciate Mussolini nor his German imitator Hitler, he considered fascism and National Socialism to be the only salvation from communism. Therefore, he also concluded a pact with Nazi Germany in 1933. According to the treaty, the Church agreed to withdraw from politics, in return it retained its autonomy and the state agreed to protect ecclesiastical associations. By means of this Reich Concordat, the Catholic Church officially recognized Nazi Germany. This was an important diplomatic victory for Hitler: his first international agreement – and it was concluded with the Pope! This gave him legitimacy throughout the Catholic world.

Italy’s Old Colonial Dreams

Military expansion also contributed to the consolidation of the fascist government. In Italy, Mussolini followed up on old colonial dreams: just like in times of the Roman Empire, he wanted the Mediterranean to become once again a “mare nostrum” – an inland water controlled by Italy. Moreover, Italy started a new conquest campaign in Africa in 1935 in order to add the Ethiopian highlands to its colonies of Eritrea and Somalia. The Italian King Victor Emmanuel III assumed the title of “Emperor of Abyssinia”. However, Ethiopia was part of the League of Nations, and the latter immediately imposed economic sanctions against Italy.

As a result, Italy’s connection to Germany grew even stronger – because Germany did not adhere to the sanctions. A few years later, in 1939, Italian troops invaded Albania. After further attempts to conquer new territories on the Balkans and in North Africa, Italy entered the World War supporting Germany. And Italian bishops blessed the troops that marched off: God was on Italy’s side.

As you can see in this gallery, the motif of the quadriga was used already in archaic coinage of ancient Greece representing a sport discipline, on coins of the Roman Republic as the carriage of Gods, and as a symbol of triumphant emperors on issues of the Roman Empire.

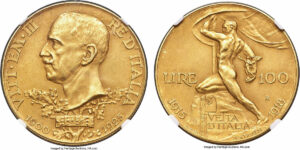

In terms of numismatics, Italian imperialism was reflected by a coin series issued in 1936 on the occasion of the proclamation of the colony of Italian East Africa. The coins featured the inscription “VITT EM III RE E IMP” (Victor Emmanuel III, King and Emperor).

The inscription “imp” for “Imperator” – the title of Roman emperors – is not the only thing reminiscent of Italy’s ancient past. The depiction of the coin’s reverse also ties in with old traditions: the quadriga, a four-horse carriage, had also been featured on coins of the Roman Republic (ca. 500-27 BC), which had been inspired by even older depictions on Greek coins.

At the same time, a British campaign put an end to Italian colonialism in Africa: in 1940, Italy lost parts of Libya and had to withdraw its troops from Italian East Africa; Ethiopia, Eritrea and Somalia came under the rule of Great Britain. This resulted in Prime Minister Mussolini losing a lot of prestige in Italy, and when the Allies landed in Sicily in 1943, the Italian government decided to take the bull by the horns: in July, the Grand Council of Fascism deposed Mussolini, and the King ordered the arrest of the Duce shortly after.

Victor Emmanuel III – a King and a Coin Enthusiast

From 1926 on, silver coins of 5, 10 and 20 lire were minted again in Italy. Even gold coins circulated: one year earlier, King Victor Emmanuel III had gold pieces of 100 lire minted. The obverse of these coins celebrated the 25-year anniversary of his accession to the throne, and the reverse commemorated World War I. By the way, Victor Emmanuel was a great fan of numismatics. In the years between 1914 and 1943, he published the “Corpus Nummorum Italicorum”, a 20-volume work on Italian coins that had been issued since the end of the Roman Empire.

The New Lira in the Struggles of the Economic Crisis

The value of the new lira quickly decreased. The economic crisis of the 1930s lead to a devaluation. In addition, the war in Abyssinia (1935/36) resulted in the League of Nation imposing economic sanctions against Italy. Italy’s participation in the Spanish Civil War (1936-1939) and the occupation of Albania in 1939 made the situation even worse. These military undertakings cost a lot. By the end of the 1930s, Italy way practically bankrupt.

Italy’s economic decline continued during World War II. The cost of living index rose from 100 to 350 within four years – from 1939 to 1943. The economic misery intensified the combat fatigue of the Italian population. But even after the Allied invasion of Italy, inflation continued to rise. By 1945, the price level was 25 times higher as in 1938; coins had disappeared from circulation, the dollar exchange rate had risen to 1200 lire. In 1927, after the introduction of the post-war lira, one dollar had cost 19 lire.

In the next episode, a second coin series is introduced in more favourable times: in the middle of Italy’s economic boom of the 1950s.

Here you can find all parts of the series “From Lira to Euro. Italy’s History in Coins”.