by Björn Schöpe

translated by Sylvia Karges

July 21, 2016 – While elsewhere detectorists are viewed as a problem and a danger to cultural heritage, England shows how relaxed one can work with another, and make important scholarly discoveries on a regular basis – just as an Anglo-Saxon settlement now.

Near Little Carlton, a town in Lincolnshire, Graham Vickers discovered remnants of an important Anglo-Saxon settlement from the 8th/9th century AD. Source: University of Sheffield.

Already in 2011, detectorist Graham Vickers found a silver stylus with precious decorations on a field in Lincolnshire near the town of Little Carlton.

The detectorist Graham Vickers (l.) and his PAS contact archaeologist Adam Daubney. Photo: University of Sheffield.

He notified the archaeologist of the Portable Antiquities Scheme (PAS), serving as a contact. As is known, the United Kingdom succeeded in integrating detectorists and hobby archaeologists in scholarly archaeology through this network.

In the early medieval period glass was a rare and highly appreciated good. Photo: University of Sheffield.

Together, they have found even more early medieval objects which indicate an above average rich settlement.

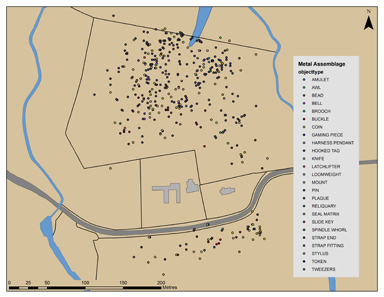

This map shows the distribution of the found metal objects. Source: University of Sheffield.

The find position of the objects was precisely measured and served the archaeologists of the University of Sheffield as a basis for their examination. In order to avoid a disturbance of the area, the findings were kept secret at first.

Dr Hugh Willmott of the University of Sheffield (l.) and Graham Vickers (r.) at the area of excavation. Photo: University of Sheffield.

Dr Hugh Willmott from the University of Sheffield explicitly praised the extraordinary cooperation with Graham Vickers: “Our findings have demonstrated that this is a site of international importance, but its discovery and initial interpretation has only been possible through engaging with a responsible local metal detectorist who reported their finds to the Portable Antiquities Scheme.”

About 100 of these silver coins (sceat) were found. Photo: Portable Antiquities Scheme.

The results of the joint research are exciting. Around 100 coins (sceattas) of the time from 680 to 790 AD document a settlement during this approximate time frame.

The first finding was a preciously decorated stylus. 21 more were to follow. This is an incredible high number for a settlement of this time. Photo: Portable Antiquities Scheme.

Furthermore, 22 styli were found – an incredible high number for this time during which such a precious tool was reserved for the intellectual elite. Perhaps monks lived here. Also, 300 dress pins, animal bones, ceramic and even glass artifacts were found.

Scratched in this lead tablet is the female name “Cudbert”. Why and who did this is unknown. Photo: University of Sheffield.

Of special interest is a lead tablet, in which the female name “Cudbert” was scratched.

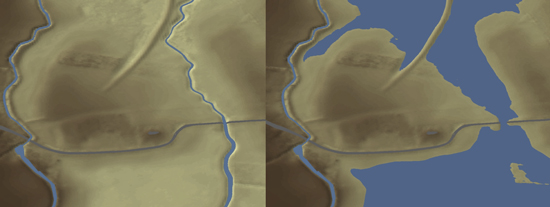

The doctoral student Pete Twonend supported Dr Willmott in the research. He conducted geophysical and magnetometry surveys.

Different geophysical inspections and archaeological excavations help to understand the site.

Whereas nowadays the finding place is located in the flat land (l.), the reconstructions show, that in ca. 750 AD the settlement was located in between rivers and lakes and was almost completely cut off from the surrounding area. The most important connection was probably by way of water. Source: University of Sheffield.

Furthermore they show, that the settled area once was an island located in marshland; back then the water level was much higher. It was through canals that the people were connected with the surrounding area. It appears that it used to be an important regional trade center or a bigger monastic settlement which existed at least for several centuries.

One part of the settlement was intended for handicraft activities, as initial excavation findings indicate. Photo: University of Sheffield.

During the excavations the archaeologists also found structures, which seemed intended for handicraft activities. Dr Willmott told the Guardian: “It’s clearly a very high-status Saxon site. It’s one of the most important sites of its kind in that part of the world. The quantity of finds that have come from the site is very unusual – it’s clearly not your everyday find.”

The end of the settlement seemed to have coincided with the Viking invasion in the 9th century. But archaeologists have so far not found any indications of a destruction by pillaging warrior hordes.

Here you will find the article in the Guardian.

Also the Daily Mail has reported in detail.