By David S. Michaels (CNG)

Having conquered the vast Persian Empire and even far-flung northern India, Alexander the Great returned to Babylon in mid 323 BC and promptly partied himself to death. His generals, the Diadochi (“successors”), slugged it out for supremacy over the next 40 years, shattering the great Macedonian Empire into several large fragments – the so-called Successor Kingdoms.

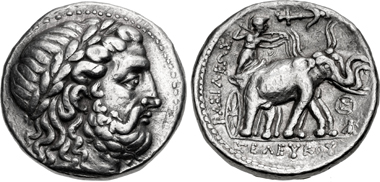

Seleukos I Nikator, 312-281. Tetradrachm, Susa mint, 300-295. From sale CNG 109 (2018), 202.

By far the largest and most populous of these was founded by Seleukos Nikator (“victor”), Alexander’s charismatic infantry commander, who proclaimed himself King in 305 BC. His realm sprawled across 2 million square miles, from southern Asia Minor to the Hindu Kush of modern Pakistan, encompassing hundreds of cities and tens of millions of subjects from dozens of ethnicities, including Persians, Armenians, Assyrians, Medes, Jews, Arabs, Afghans, Indians, Scythians and, of course, Greeks. It survived, in some form, for two and a half centuries.

Antiochos II Theos, 261-246. Stater, Tarsos mint, ca. 261-253. Ex Arthur Houghton Collection. From Sale CNG 109 (2018), 231.

Following the trail blazed by Alexander and employing vast stores of bullion “liberated” from Persian treasuries, Seleukid rulers produced an extensive coinage in gold, silver and bronze from dozens of mints. Yet, until fairly recently, it remained a rather overlooked realm of numismatics, overshadowed by other Classical and Hellenistic Greek states, particularly the neighboring Ptolemaic Egypt. The tide began to shift in the late 1960s, when Seleukid coins found a champion in Arthur A. Houghton III, scholar and diplomat, who assembled an extensive collection and authored several monographs and books on the subject.

Seleucid Coins Online – a useful tool for collectors and scholars provided by the ANS.

The last 20 years have witnessed an explosion of scholarship devoted to Seleukid coinage, providing collectors and historians alike with excellent, deeply researched references to guide them. These include the monumental Seleucid Coins, Parts I and II, by Arthur Houghton, Catherine Lorber, Oliver Hoover, and Brian Kritt, and the compact and useful Handbook of Syrian Coins (HGC Series 9) by Hoover. Only this year, the American Numismatic Society launched its “Seleucid Coins Online” website, an invaluable website devoted to the series.

Portrait of Seleukos I. Archaeological Museum Naples. Photo: KW.

Consequently, collectors at every level have discovered the Seleukid series and brought this attractive and historically illuminating coinage long-overdue attention. The coins themselves provide an astounding “facebook” of rulers, often with portraits of great artistry and near-photographic realism. These rulers are an eclectic and colorful lot, with both heroes and villains, the brilliant and indolent, the decent and tyrannical, the enlightened and decadent. Mostly men are depicted, although a few ferocious women left their mark as well.

Antiochos IV Epiphanes. Tetradrachm, Antioch in Persis mint, 175-164. From sale CNG 109 (2018), 189.

Seleukid coins are widely available in every price range, from $10 small bronzes to exceptionally rare and beautiful gold pieces that have achieved auction prices in excess of $275,000. The most widely available denomination is the silver tetradrachm, usually weighing about 16-17 grams and between 25 and 30 millimeters in diameter. A pleasant VF tetradrachm of a common ruler can cost less than $200, with particularly artistic portraits priced at a premium. Rarities, of course, run much more. However, a modest investment in time and money can thus produce a collection of large, impressive coins spanning an exciting and transformative era in history, when east did in fact meet west, and produced something beautiful.

Here are a few brief bios of some of the most important and intriguing Seleucid kings and queens, and the coins they created:

Seleukos I Nikator. Stater – Double Shekel. Babylon II mint, 311-305. From sale CNG 195 (2018), 195.

Seleukos I Nikator (312-281 BC): The Seleukid Kingdom’s first ruler was also one of its longest-lived, reigning more than 30 years and providing his descendants a tough act to follow. Born into the Macedonian military gentry, he was clearly a talented soldier and present at most of Alexander’s major battles, although he never entered the great conqueror’s inner circle. After Alexander’s death, he became commander of the elite Companion Cavalry attached to the regent Perdikkas, but quickly abandoned and assassinated his overlord in 321 BC during a disastrous attempt to suppress the satrap Ptolemy in Egypt. In the resulting carve-up of empire, Seleukos won the coveted satrapy of Babylon and, through brilliant stratagems and sheer tenacity, defeated or outlasted a succession of formidable rivals to end up as supreme commander of all Asia and the Hellenistic near-east.

Philetairos of Pergamon. Tetradrachm, Pergamon mint, 269/8-263. On the obverse a portrait of Seleukos I Nikator. From sale CNG 109 (2018), 214.

He formally named himself Basileos, or King, in 305 BC, but retroactively dated the foundation of his kingdom to 312/1 BC, the beginning of the “Seleukid Era.” Despite his great success, his personality remains somewhat opaque, though he seems to have been loyal (he kept the Persian wife, Apama, given to him by Alexander when the other Macedonian officers quickly abandoned theirs), and humane, by the standards of the age (he rarely executed a defeated rival, preferring to keep them in comfortable captivity).

Seleukos I Nikator. Tetradrachm, Susa mint, 295-281. From sale CNG 109 (2018), 205.

His coinage is vast, complex, and fascinating, struck at a profusion of mints, with major design changes occurring at roughly five-year intervals. Initial types struck during his Satrapy bear the familiar types, names, and titles of Alexander the Great, with the symbol of an anchor (inscribed on his iron signet ring, supposedly given to him by his mother) appearing as a control mark. After Seleukos adopted the royal title in 305 BC, a new type emerges with a handsome male head wearing a horned Attic-style helmet covered with a panther skin and sporting bull’s ears, all attributes of Dionysus. Scholars have long debated whether the head represents Seleukos himself, or Alexander, or Dionysus, or a synthesis of the three. More recently, opinion has tilted toward the simplest view: Seleukos himself, making this one of the first Hellenistic portrait types. The reverse depicts Nike erecting a trophy of arms, a design that reverberated down through the ages. After Seleukos negotiated 500 war elephants from an Indian king, a new silver tetradrachm type was issued in circa 296 BC, pairing an obverse head of Zeus with a reverse depicting Athena in a chariot pulled by elephants. Elephants went on to play a major role in Hellenistic warfare, though sometimes proving as dangerous to the side using them as to their foes.

The second part of this article will acquaint you with Antiochos III called “The Great”, another Antiochos calling himself “God Manifest” and the divine Cleopatra – not to be confused with the identically named lover of Roman generals.

More information and past and future CNG sales is available online.

Author David Michaels rejoined the CNG on July 1, 2018 to help reestablish their presence at U.S. coin shows.

You can contact David Michaels via e-mail.