by Ursula Kampmann

September 26, 2013 – In the beginning was the Word. The tentation to start this text with these words from the Gospel of John was just too seductive. Because, actually, at the beginning of this display was not a marketing team looking for some pretty topic but a team of researchers spotting, arranging and catalogising painstaikingly all material traces of Carolingian culture in Switzerland.

Entrance of the exhibition. Photo: UK.

The result of this searching for traces is a comprehensive book with the title ‘Die Zeit Karls des Grossen in der Schweiz’ (‘The Epoch of Charlemagne in Switzerland’). And the display was intended to be only a by-product. That it has taken a life of his own, though, becoming a magnificent overview on Carolingian works of art, is another story.

Anyhow, CoinsWeekly visited the exhibition – and we were thrilled. In a reasonable limit many valuable works of art have been gathered here in order to give at least an idea of how splendid Charlemagne’s imperial residence once was.

Equestrian bronze statue of Charlemagne, made on behalf of the Metz cathedral under the reign of Charles the Bald (843-877). Bronze replica. Louvre / Paris. Photo: UK.

The first subject the display faces is, naturally, Charlemagne himself and his family. His famous equestrian statue made on behalf of the Metz cathedral under the reign of Charles the Bald is prominently erected in the centre of the hall. It is a replica, though, because the original is no longer given away as loan being it a national monument of France that considers Charlemagne its founder.

With many images, video clips and audio stations the visitors learn much about the historical background of Charlemagne, and these presentations are really well done. The employment of modern medias in this display has indeed worked out perfectly.

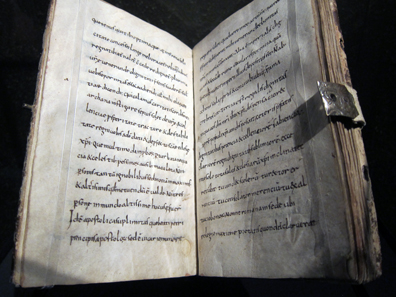

Alcuin’s letters to Charlemagne. Klosterstift St. Gallen. Photo: UK.

However, what would have been the mightiest ruler without an army of collaborators? Christine Keller, exhibition curator, called Charles an excellent networker. And indeed, the capacity of the Occident’s first emperor to attract eminent personalities from the whole world as it was then known and to employ them according to his needs, is remarkable. Full of symbolism the display presents eight of Charles’s closest collaborators in a mystical octagon evocating the Palatine Chapel in Aachen.

A tenth-century copy of Charlemagne’s biography written by Einhard. Stiftsbibliothek Kloster Einsiedeln. Photo: UK.

From the distant England Ealwine had come, today known to us better as Alcuin, whose actions are linked to the introduction of the Carolingian minuscule. Another counseller was Einhard, author of Charles’s first biography written already in 830, just one and a half decades after his death.

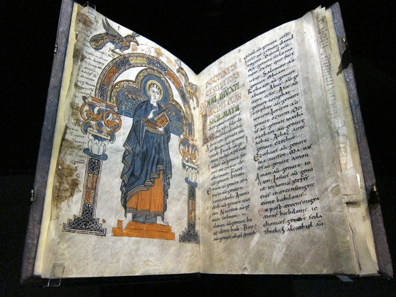

Books symbolise the achievements of these men. They can be admired in an opulent choice of manuscripts. The incredible variety proves to what extent Carolingian manuscripts have been preserved in the important Swiss libraries of St Gall, Einsiedeln, Bern and Zurich.

Treasure of Ilanz. Rätisches Museum, Chur. Photo: UK.

Education and coinage – these were the fields where Charlemagne’s deeds have lasted particularly. And in both of them he bet on standardisation. To achieve that everyone who was able to read understood what his emperor wished him to do, Charles established a standardised, easily legible script, known as the Carolingian minuscule.

With regard to the coins it is really unnecessary to repeat another time that the Carolingian coin system with a pound of 20 shillings or 240 denarii had lasted until after World War II. In this matter Charles followed his father Pippin, who had again monopolised for the king the right to issue coins.

Denarius with the portrait of Charlemagne. From Künker auction 205 (2012), 1405. Lender: Herb Kreindler.

In contrast to the bronze statue of Charlemagne this coin on display is genuine, although we must admit that it was not issued in his lifetime but under his son Louis the Pious.

The section dedicated to the coins. Photo: UK.

It is a shame that Codex 731 from the St Gall abbey library is not exhibited. The pattern of the wall decoration in the coin section comes from that book. In this ‘Lex Romana Visigothorum’ penned by the clergyman Wandalgarius in Lyon a man is depicted raising a denarius with Charles’s monogram as to show it clearly to all readers.

View into the exhibition, in the foreground a nineteenth-century model showing how they imagined at the time the Plan of St Gall being realised in the Middle Ages. Photo: Schweizerisches Nationalmuseum.

From the general to the specific. From the ideal Plan of St Gall to the actual Carolingian abbeys in Switzerland and their treasures of art.

Original and reconstruction of the coloured stucco that adorned once the abbey church of Müstair. Photo: UK.

Architectural fragments from Müstair, Chur and Disentis illustrate how sumptuously the imperial abbeys were decorated.

Silk cloth from the Chur cathedral, made in Byzantium or Syria at the end of the eighth or the beginning of the ninth century. Domschatz Chur. Photo: UK.

Superb cloths, …

Reliquary from the Abbey of St Maurice. Treasury of the Abbey of St Maurice d’Agaune. Photo: UK.

… reliquary shrines …

Liber Viventium. Klosterstift St. Gallen. Photo: UK.

… and richly illuminated liturgical manuscripts: What an incredible wealth one could admire in the imperial abbeys we hardly can imagine today.

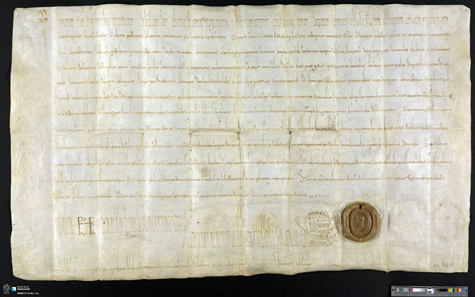

Gift from King Louis to the Fraumünster Abbey. Photo: Staatsarchiv des Kantons Zürich.

Charles and his successors employed these abbeys systematically to assure that people perceived them as emperors through their representatives also in remote regions. Thus Zurich assumed quite an important role in the Carolingian realm. Louis the Pious donated Fraumünster Abbey to his daughter Hildegard on July 21, 853 who took control over these rich possessions as abbess.

Pippin and Charlemagne with the model of the Zurich Großmünster, c. 1551. © Schweizerisches Nationalmuseum. Photo: Donat Stuppan.

And Zurich thanked Charlemagne by venerating him particularly. Even today Charles sits enthroned over the Großmünster, which – due to its continuous rivalry with Fraumünster Abbey – created itself the legend of being a foundation of Charlemagne.

You can learn more about that in the section ‘Reception’ that closes this entertaining and instructive exhibition.

You can find all information on ‘Charlemagne and Switzerland’ here.

In case you cannot visit the display personally we recommend to you the sumptuously illustrated book on Carolingian treasures of art in Switzerland. You may also use it as a kind of traveller guide to the various locations.

There is a wide range of presentations, guided tours and events some of them with regard to numismatics. You can learn more about them here.

Very impressive is the multimedia reconstruction of the Carolingian Residence at the Zurich Lindenhof. To watch it please click here.

And here you can listen to Zurich’s legends of Charlemagne (only in Swiss German, though).