by Ursula Kampmann

August 1, 2013 – Sometime between 819 and 826, a monk of the Reichenau Abbey started to dream about a model monastery. On a parchment measuring 112 cm x 77.5 cm he drew a sketch of what he imagined a monastery could look like.

Plan of St. Gall. Reichenau, early 9th century. Source: Wikipedia.

The plan shows fifty or so buildings whose functions are specified in 333 inscriptions. This number in itself proves the plan to be ideal. 300 is the Biblical numeric value of the spirit of God (ruach elohim), 33 stands for the number of years Jesus had lived. Old and new testaments are joined together in this new Jerusalem of which the monk dreamt in his own monastery on the Reichenau island.

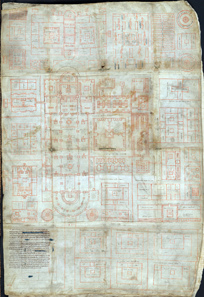

J. R. Rahn. Reconstruction of the plan from 1876. Source: Wikipedia.

Naturally, the monastic church, a magnificent edifice, was located at its center. Grouped around are scriptorium, sacristy, guest house and cloistered courtyard, dormitory, refectory, toilets and lavatorium. And there are the industrial out-buildings, kitchen, bake and brew house, abbot’s residence, infirmary and novitiate. This vast compound very likely accommodated more than 100 monks and roughly 200 workpeople and servants.

The new inhabitants of the monastic city move in. Photograph: Campus St. Galli.

It is this plan the citizens of Messkirch have taken as model to add a great attraction to their small town.

The municipal church St. Martin, monument for Conradin Kreutzer in front of it. Photograph: KW.

With its 8,200 or so citizens, Messkirch is a nice city in Upper Swabia, a little remote from the flow of tourists coming to see Lake Constance. However, a not so small Renaissance castle is there to be visited as well as a municipal church, built around 750, honoring St. Martin which today is very much dressed like Rococo.

Tomb of Gottfried von Zimmern who had died in 1554. Photograph: KW.

The history of Messkirch is impressive. It was mentioned for the first time in the 11th century. Allegedly, St. Heimerad had been born here around 965, according to the vita. Messkirch became a market in 1241 at least and a city in 1261. Under the noble family of those von Zimmern, the city came into bloom in the early modern period of which we are told in detail by the Zimmern Chronicle.

Messkirch town hall. Photograph: KW.

At some point at the end of the 19th century, Messkirch sank into insignificance. Only few non-locals know the place at all or are aware of the fact that this is the birth place of philosopher Martin Heidegger or composer Conradin Kreutzer. This, however, is all going to change thanks to an ambitious project borne by the citizens’ enthusiasm.

Opening ceremony of Campus St. Galli, to the left the project’s initiator and chairman of the board, Bert M. Geurten, to the right the head of site, Verena Scondo. Photograph: Campus St. Galli.

After all, the monk on the Lake Constance island of Reichenau isn’t the only one who dreamt of a perfect monastery. He gets company by Bert M. Geurten, Rhinelander, citizen of Messkirch and aficionado of the French medieval construction project of Guédelon Castle. He wanted to make a dream come true and do something to boost the region’s infrastructure at the same time. The Campus St. Galli project after all has the potential to become a national tourist attraction.

The entrance. Photograph: KW.

More than 40 years are appointed for the building process. The craftsmen have already moved in their temporary log-built accommodations. CoinsWeekly has visited the monastic city in the making on 20th June 2013, two days prior to its official opening.

Earth wall around the monastic area. Photograph: KW.

Despite the modern appearance of the entrance, the monastic area isn’t wired but surrounded by an earth wall in which the uprooted logs were incorporated to prevent anyone from climbing over.

The Gallus Hermitage. Photograph: KW.

The visitor is directed through a small medieval settlement on a fixed circuit. First stop is the so-called Gallus Hermitage, the monastery’s nucleus. It was such buildings where, after the death of St. Gallus, monks had lived before they built a stone accommodation in St. Gall. The monks were followed by craftsmen settling round such hermitages, who consisted partly of free men, partly of bondsmen of the monastery the saint had been given as thank-you gift from pious Christians for his rogation in the hereafter.

The hen house. Photograph: KW.

The tour’s next stop, only a few meters further, is the hen house. After all, the chicken is one of man’s most ancient tamed animal source food. The first finds concerning European poultry keeping come from Heuneburg, located not far away. And the Romans made sure that Swabians, too, got used to eggs and chicken.

The hen house is a case in point for the difficulties the organizers face, because reconstructing the Early Middle Ages in its entirety is difficult. Animal rights activists surely would complain vehemently about the fate of the chicken exhibited if they were approached by children trying to pet them all the time. The answer to this is an unhistorical wire-netting fence preventing the chicken from escaping.

The hen house is kept together by treenails. Photograph: KW.

And which makes the critics overlook how careful this small building was reconstructed. There is no such thing as metal nails but pointed wooden dowels with which the branches are fixed.

Front door of the hen house. Photograph: KW.

The front door, in addition, consists of casual willow wickerwork.

The working place of the pottery maker is being prepared. Photograph: KW.

At this place, a pottery maker has started working on 22nd June. The wheel serves as pottery wheel, rotating around the wooden dowel in the picture’s center.

The smith working. Photograph: Campus St. Galli.

A little further on one can watch a smith working.

Little herb garden. Photograph: KW.

His working place is right next to the unavoidable herb garden. In early medieval times, herbs were not only used to upgrade the daily pulp as regards taste but likewise to cure minor bodily afflictions and for dyeing.

Bee house. Photograph: KW.

Just like honey, which wasn’t just the only sweetener known in the Middle Ages. In addition, it has an anti-inflammatory effect and was used to treat wounds. And the small animals produced the precious beeswax that was much too valuable to be used for mundane purposes. The gorgeous candles made of beeswax remained reserved for religious service. Beehives were considered so valuable that thieves of bee houses got their hands cut off or were executed straightaway as late as the Late Middle Ages.

Oven. Photograph: KW.

A built oven is another attraction of the monastic city where craftsmen demonstrate their ability until 11th November, every day except Mondays.

The entire village is involved in the preparations. Photograph: KW.

Apparently, the whole of Messkirch is involved in the preparations around the monastic city – and that is great in itself!

But, as a matter of fact, many critical voices have been raised, too. The major bone of contention is that the locals aren’t very particular with the Middle Ageness, as it were. The question remaining is how far can authenticity go? One person sees no harm in wearing modern underclothes underneath the medieval garments, while another person already condemns that as being unhistorical.

Every mega project has to live with compromises, even the more so when the major aim is to attract visitors. Unfortunately, that is much easier achieved when something spectacular is involved than with mere historical accuracy. In plain terms, Campus St. Galli is no scientific project with a clearly defined academic interest but the private initiative of a society of committed and enthusiastic citizens, supported by politics, which intend to attract tourists. The latter’s admission charges hopefully will fund the project on a permanent basis.

It would be unfair to already pass judgement on Campus St. Galli, now that the building has just begun. It remains to be seen how the matter develops, if a success turns Campus St. Galli into a kind of archaeological Disneyworld or if sufficient funds on hand promote the reconstruction to become as accurate as possible. Anyone looking at the project with his eyes open will realize that at present many areas need to be endowed better.

Anyhow, CoinsWeekly will have a look at the construction site’s progress at regular intervals to whet your appetite a bit so that you might visit this Upper Swabian variant of experimental archaeology yourself.

Further information on this project is available at the society’s website.

This is where you can find all details regarding opening hours and entrance fees.

A short film (in German) on Campus St. Galli you can watch on YouTube.

There, you can also listen to the most famous works of Conradin Kreutzer, composer born in Messkirch.

A critical voice (in German) on Campus St. Galli you find here.

More information on the Guédelon project, that has become the model for Campus St. Galli, you can gain here.