The Künker Auction 341 will be held on 1 and 2 October 2020. It will feature, among other pieces, a large selection of coins featuring Agrippina’s portrait. When we look closely at these coins’ message, we begin to doubt whether Agrippina really deserved her awful reputation.

Casus suorum

How different would our idea of Agrippina the Younger be today if the historical work she’d written – entitled ‘casus suorum’, roughly translating: the destiny of her family – had survived. Unfortunately, we don’t have it, meaning we have to rely on the testimonies of men in order to reconstruct Agrippina’s life. And who were these men? They were senators who were still sulking about the fact that, in the new political system of the Principate, they had to rely on the imperial family in order to play their power games.

And then there was Agrippina, a biological great-granddaughter of Augustus. She was not only beautiful but also intelligent and, despite all barriers, prevailed in the struggle for ultimate power. So we’re looking back at her story – and we won’t be treating what Tacitus and Sueton wrote about her as any more than what it was: slander.

The Great-Granddaughter of an Emperor

On 6 November in 14, 15 or 16 AD, Agrippina was born in Oppidum Ubiorum, which later developed into the city of Cologne. And thus her fate was sealed, as she was descended from Augustus on both her father’s and mother’s side. Her mother Agrippina the Elder was a biological granddaughter of the first emperor, while her father Germanicus was the grandson of Augustus’s sister. A man with this kind of family tree became emperor; a woman became a plaything of marriage politics.

And it was no different for Agrippina. Tiberius married her off when she was 14 years old – and that’s the best-case scenario, she may also have been 12 – to a 44-year old senator. It was to this senator that she bore her only son, the future emperor Nero.

The Sister of an Emperor

In AD 37, Agrippina’s brother Caligula assumed the imperial throne. The senators hailed the young man as their great beacon of hope. How quickly they were disappointed! The Senate historians explained their initial support of the later ‘monster’ by claiming a mysterious illness had suddenly changed the young emperor’s character.

Unlike Agrippina. She joined forces with her sister and the husband of her recently deceased second sister to murder her insane brother. The plan failed and Agrippina was exiled to the Pontine islands. It would have saved Rome a lot of trouble if the three of them had succeeded. Perhaps they weren’t driven by ambition, as many historians still assume to this day, but rather by a sense of responsibility towards Rome.

The Wife of an Emperor

Agrippina’s uncle Claudius lifted her exile shortly after coming into power. Historians have known for a long time that this emperor was not the naive fool the Senate historians would have us believe. It was clearly rather embarrassing for Tacitus or Sueton that Caligula, who had been chosen by the Senate, had turned out to be a tyrant, while Claudius, made emperor by the soldiers, was a capable ruler. And then Claudius was intelligent enough to depend on skilled freedmen rather than self-indulgent senators.

One of his most competent advisers was Marcus Antonius Pallas, who managed the imperial finances. He suggested that Claudius marry his own widowed niece Agrippina – of course, if we choose to believe the worthy senators, this was just because Agrippina had slept with the former slave. And the foolish Claudius was supposedly blinded by her unparalleled beauty…

When we look more closely at the facts, it becomes clear that there’s definitely another interpretation: the Roman people had applauded Agrippina and her son during an event in the AD 47 Secular Games, and their applause had been noticeably louder for her than for the emperor’s then wife Messalina and her son Britannicus.

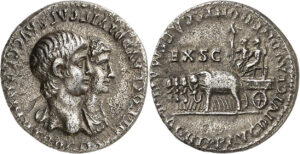

Agrippina was also more closely related to Augustus than Claudius himself. The marriage to Agrippina, which took place on New Year’s Day in AD 49, was therefore a real PR stunt for Claudius, which he used to boost his popularity. And this interpretation is supported by one piece of fundamental, unbiased evidence: the coins. Why else would Claudius have issued such a high mintage into circulation with such a prominent portrait of Agrippina if not to win the approval of his citizens and soldiers? After all, prominently incorporating a living empress into a coin design was something no other Roman ruler had done before him!

Another advantage of this marriage for Claudius was the fact that, at that time, Agrippina’s son was already 11 years old. This meant there were only three years left until he came of age, while Claudius’s biological son Britannicus was just seven years old. Claudius was ailing and, being a historian, he knew just how much misery the Roman civil war had brought about after the assassination of Caesar. He didn’t want another war to break out and Nero, who was, after all, the biological great-great-grandson of Augustus, was his way of stopping that from happening. That’s why he proclaimed Nero his successor and had him depicted on the many coins circulated among the people.

We can assume that Claudius was intelligent enough to know what he was doing when he adopted Nero, thereby placing him next in line to the throne ahead of his own son Britannicus, who was perhaps not free of controversy owing to the fact that his mother had been executed for adultery.

If Agrippina had been the scheming serial poisoner the senators portrayed her as, she would surely have chosen a different tutor for the future emperor Nero than, of all people, the stoic philosopher Seneca. She lifted his exile for that express purpose. That was a mistake.

The Mother of an Emperor

On 13 October 54, Claudius died after eating a plate of mushrooms at a banquet. Of course, Agrippina was accused of poisoning him. This would make him her seventh victim, if we are to believe the Roman historians.

The power was handed over without any problems. Agrippina, in agreement with her son, took control of government. And that, for any Roman senator, was downright scandalous. She was a woman! Disgusting! Tacitus and Suetonius both tell us what happened next: Nero fell in love with the freedwoman Acte, an affair that Seneca encouraged to the best of his ability. Agrippina, who was very morally strict, gathered all her motherly authority and tried to encourage the defiant Nero to focus instead on his wife Octavia.

And so, the inevitable happened: the adolescent Nero distanced himself from his mother and turned instead to Seneca and Burrus, who, in the years that followed, did whatever they wanted. Among their victims was Pallas, the former financial advisor to Claudius. Over the next four years, Seneca’s personal wealth mysteriously increased by about 300 million sestertii. He took advantage of Nero’s favour, and even his peers were powerless against it. Seneca, like Verres, was prosecuted in the Senate for his ruthless exploitation of the provinces – and he got off scot-free, while his accuser was sent into exile.

Seneca thanked Nero by helping him to organise the murder of his mother and then writing the official letter informing the Senate about her death.

No woman could blame Agrippina, or the ‘Optima Mater’ (‘best of mothers’) – this was the password Nero gave to his soldiers on his first day in power – for asking her assassin, hired by Nero, to thrust his sword into her womb, in order to destroy the part of her body that had created her son.

Here you can read the comprehensive preview of the Künker Fall auctions where these coins will be on offer.