by Ursula Kampmann

October 25, 2012 – Hall in Tyrol. We have to spell it completely in order to avoid any confusion. After all there are many towns sounding quite similar to the English speaking world: Hallein, Hallstadt, Reichenhall, Halle, Schwäbisch Hall. They all share one aspect: In all these places salt was mined, and in the Middle Ages “hall” was the German word used for salt.

Hall in Tyrol, in the foreground Hasegg Castle, housing today the coin museum. Photo: Herbert Ortner, Vienna / Wikipedia CC-Licence.

The Hall salt pans were mentioned for the first time in 1232. The counts of Tyrol – first the Meinhardiners, then the Habsburg – invested in this place creating thus their wealth which would lead to their ascent. At this epoch salt was considered the white gold since it was the only way of curing meat and fish, being therefore one of the paramount resources of the pre-refrigerator epoch.

Hall in Tyrol. Medal 1903 by Stefan Schwartz in occasion of 600 years town of Hall. The patron deity on the left holds the town’s coat of arms in her lap. From Rauch summer auction 2012, 2321.

Actually Hall’s coat of arms recalls this past. It shows a wooden barrel particularly employed for the transport of salt and which had therefore become a standardized measure by the fourteenth century. The golden lions of the coat of arms, by the way, were only added by Maximilian I in 1501.

Sigismund the Wealthy (1446-1496). Guldiner 1486, Hall. From Künker 201 (2012), 379.

At this time, Hall was a prosperous city, owing its wealth not only to the salt but also to the trade. There, the merchants were able to cross the River Inn over a bridge, and the river was navigable right up to Hall. Two important fairs took place in Hall, and since 1486 there was the mint where silver from the neighboring Schwaz was transformed into coins. In this golden age, Hall was approximately twice as big as nearby Innsbruck.

Parish church St Nicholas of Hall. Photo: KW.

This is testified still today by Tyrol’s largest old town which, in the meantime, has been tenderly restored. Particularly the Upper Square (Oberer Stadtplatz) with the townhall, the ‘Stubenhaus’ and the parish church St Nicholas merit an in-depth visit before approaching the museum ‘Alte Münze’ (Old Mint).

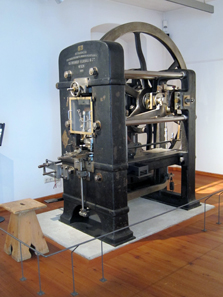

Knuckle joint press. Photo: KW.

At Hasegg Castle the mint had been accommodated since the sixteenth century. Today it houses a unique museum of minting technology where the visitors can admire a great number of original minting machines and replicas. An audioguide in several languages gives particularly thorough information at hand and is, therefore, of special interest for coin collectors who go there with their family. Indeed they offer a special children version as well that gives an understanding of the objects in an age-appropriate and at the same time intriguing way.

In the first room you will see the most modern machines, as for example a knuckle joint press.

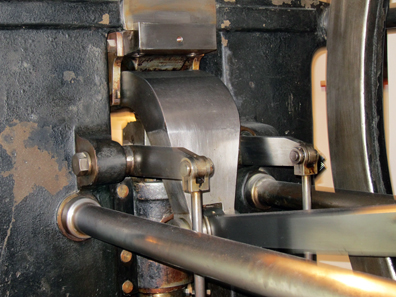

Detail of the knuckle joint press. Attachment of the joint employed for lifting and lowering of the press. Photo: KW.

The knuckle joint press was, indeed, a modern way of minting circulation coins not only in the nineteenth but well into the twentieth century.

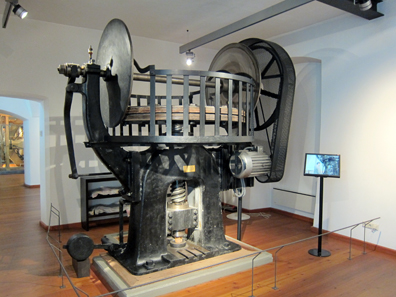

Friction press. Photo: KW.

Medals, on the other hand, were more commonly produced by friction presses. These machines are based on the screw press concept. Enormous flywheels transferred a slowly incremental pressure onto the metal conferring, thus, to the nineteenth century medals a relief that modern mints are not able to yield.

In the deepened hollow a person was crouched inserting the blanks. Photo: KW.

Of course minting was slower here as with the knuckle joint press since one man crouched into a deepened hollow had to insert every single blank manually.

Screw press. Photo: KW.

In the next room the precursor of the friction press is exposed, the so-called screw press, a machine that has to be operated manually. Many of you have experienced this way of minting personally, I am sure: Pushing vigorously you make the screw to lower inside the spindle as it is propelled by two heavy spheres.

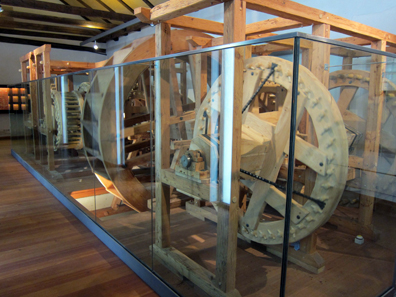

The replica of the roller coining machine fills the whole room. Photo: KW.

Though, that is not the real highlight which awaits the visitors only in the following room. There a roller coining machine is placed, a machine which fills the whole room. Naturally, it is no original, but it was reconstructed with extreme dedication by Werner Nuding who was helped by many others – numismatists, historians, archivists. The machine is even put into operation during guided visits and it is highly recommended to see with one’s own eyes how a stannic fillet is pressed through two rollers.

Once gigantic mill wheels animated this machine. Photo: KW.

Once the gigantic wheel in the middle was animated by water energy. In locations where this was not practicable – for example in Potosi – animals were employed. Today an electric motor by propelling the big wheel sets in motion two other wheels which on their term keep in service a rolling mill on one side and the roller coining machine on the other.

Rolling mill. Photo: KW.

Since the high Middle Ages water mills were used as an energy source that permitted shredding the corn but also performing a lot of various tasks. There were mills for oil production, milling, sawing, hammering or grinding, just to cite a couple of examples. At a certain time some bright fellow got the idea to apply the correct thickness to the fillets by operating a mill.

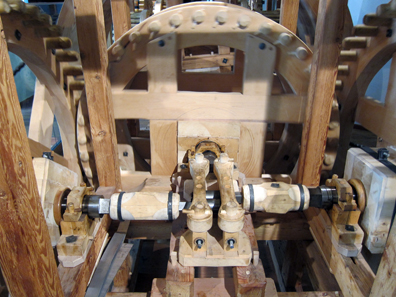

Roller coining machine. Foto: KW.

Indeed, it was not a big step any more to cut the coin design concurrently into the rollers. In Hall they succeeded in rendering this technique suitable for mass production. From Hall machine components and specialized technicians were sent out to other mints in order to teach them how to operate such a machine.

Rollers. Photo: KW.

Actually, cutting the rollers was not a simple work at all.

A stannic fillet and one made out of birchbark. Photo: KW.

It was necessary to slightly compress the coin design hence it would transmit correctly the image onto the metal. An imprint on birchbark shows how precisely the roller cutters accomplished that task.

Money chest. Photo: KW.

The last room is dedicated to the traditional minting process using a hammer, then you reach the patio.

Patio with feastful decoration. Photo: KW.

Although today it is difficult to imagine, once this patio was very colorfully painted since the Count of Tyrol whished to impress his many aristocratic guests and diplomats with his roller coining machine.

Remnants of the painting. Photo: KW.

Now we can see only some remnants of the painted decoration.

Furnace. Photo: KW.

However, Hasegg Castle owns an original furnace as it was operated to prepare silver for the minting process and control its quality.

Tools. Photo: KW.

This marks the end of a visit of the Old Mint museum. You may, though, decide to mount the tower, which I recommend vividly because it offers a really great panoramic view, and visit the museum of urban archaeology.

Souvenir shop. Photo: KW.

Well, there is only the souvenir shop left. There you can mint your own medal on a screw press or purchase books on the subject. Additionally you will find many T-shirts and lots of prezzies.

Bernhard Beheim. Photo: KW.

And in case you have some time at disposition, do not forget to stroll over the churchyard. You will find an epitaph of Bernhard Beheim the Older – the man who supervised the coining of the very first thalers.

If you want to learn more about the Hall mint, please click here.

You may whish to read a text on Bernhard Beheim here.

If you are fascinated by minting technology we recommend a journey in time through six mints from the sixteenth century until 2003.

Just now a congress was held in Hall on the mint’s relevance to Europe. You can read our report here.