by Ursula Kampmann

December 6, 2012 – Today Gotha is a nice little town of some 50,000 inhabitants. However, in 1643 Ernst I of Saxe-Gotha decided to shape the place a capital that could keep up with other towns on an international level.

Ernst I the Pious, 1640-1675. Reichstaler 1675 in occasion of his death. From Emporium Hamburg auction 68 (2012), 1648.

Ernst, as nearly all of his nine brothers, served as a colonel to the Swedish army during the Thirty Years’ War. Thus he knew the horror of the battle field and how much the civilians feared plundering. No wonder he yearned for another time and called the castle erected in an inherited territory ‘Schloss Friedenstein’ (‘Palace of the peace rock’). It was, indeed, conceived as a gigantic palace typical of the early baroque. Splendour took the place of actual power of which, most probably, the small Duchy of Saxe-Gotha was lacking.

Schloss Friedenstein – seen from south. Photo: KW.

Schloss Friedenstein was not only destined to live in. All institutions of the then new state were housed there, some rooms were intended for the administration of the country, other for the archives. The stables, the smithy and the arsenal made it clear that this place was the heart of the state’s military defence, too. A theatre which is still conserved, displayed the importance of the duke’s court to the artistic world.

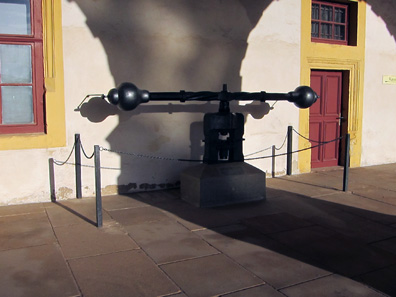

Screw press in the arcades. Photo: KW.

And, of course, the mint was placed as well in Schloss Friedenstein – at least for some years. It was located where you can find the restaurant today. The early coinage was definitely not economically relevant. These issues served as representative objects and displayed the duke as a pious man – the result is, indeed, that this is how he is still called today.

Detail of a silver medal by Nikolaus Seeländer showing an allegory of how the Gotha coin cabinet was installed by Duke Fredrick II, 1713. Photo: KW.

Basis of the collection you can see today in Gotha was a portion of the Ernestine art collection Ernst I had inherited. Its quality and the exquisite objects certainly astonished and overwhelmed the connoisseurs of the epoch and they are still doing so now. Whoever decides to visit the palace should calculate three, four hours at least if they want to appreciate the material adequately.

Cranach room in Schloss Friedenstein. Photo: KW.

Do you love the art of the Reformation? Well, in that case you should calculate sufficient time for the rooms that accommodate Gotha’s really important Cranach collection.

Coins and miniatures are exhibited closely side by side in order to permit a comparison. Photo: KW.

Particularly pleasant is how they have arranged closely together portraits of key figures of the Reformation painted by Cranach, and coins and medals of the same eminent persons.

Frederick the Wise, Elector of Saxony, painted by Lucas Cranach the Older 1536. Photo: KW.

Numismatically significant persons like Frederick the Wise …

Saxony. Frederick August III, 1904-1918. J. 141. From Künker auction 213 (2012), 6077.

… – known to the coin collector particularly for the fact that his portrait is displayed on the most expensive coin of the German empire – can be admired here in original portraits from their time.

John Frederick I, Elector of Saxony, called The Magnanimous, painted by Lucas Cranach 1535. Photo: KW.

We coin collectors know other princes as well rather from portraits on coins, like John Frederick I, Elector of Saxony.

John Frederick I ‘The Magnanimous’ when he was still a duke, 1552-1554. Double gulden, 1552, Saalfeld. From Künker auction 100 (2005), 451.

This is a representative gold issue. You can clearly recognise the short-cut hair and the striking beard which Lucas Cranach considered to be so peculiar features that he included both in his portrait.

Portrait of Erich Volckmar von Berlepsch, painted by Lucas Cranach 1580. Loan of the Kleinurleben parish. Photo: KW.

Although this sir has never attained numismatic honours you should give a closer look at his portrait. Because here you can see what the so-called gnadenpfennige were used for: they were carried on a chain in an eye-catching way as if they were a decoration of an order. With this you showed courteously to your counterpart how much you were admired among the (very) rich and nice ones.

Portrait of Emperor Henry IV of France from a series of important rulers, painted before 1593. Photo: KW.

You can notice how quickly time passes on in these rooms. It took us nearly three quarters of an hour until we spotted the next numismatic highlight (less then 100 metres distant from the Cranach room). In the middle of a series of miniatures of contemporary rulers so extensive as I had seen previously only in the coin cabinet of the Historisches Museum in Vienna …

Looking into one of the showcases. Photo: KW.

… is placed a selection of the finest Renaissance coins and medals. We must, though, omit the brakteats (all of them without exception are magnificent) because the photos did not turn out well. Nevertheless we passed another three quarters of an hour in this room even though we were actually pressed for time.

Bust of duke Frederick II of Saxe-Gotha-Altenburg. Photo: KW.

And we have to say that until that point we had not even reached the main part of the coin exhibition. The representative rooms were really impressive and all the time, we came across busts of rulers known to us from coins.

Frederick II. Silver medal from 1703 by J. C. Koch to commemorate the duke’s virtues: equity, piety, charisma, wisdom, moderation, bravery and benevolence. From Künker auction 211 (2012), 3478.

One of them is this: Frederick II of Saxe-Gotha, or of Saxe-Gotha-Altenburg as he was called since 1672. He was very fond of numismatics and, in 1692, he appointed Ernst Tentzel curator of the coin cabinet. Tentzel was a famous numismatist who published the ‘Saxonia Numismatica’ which is, even nowadays, still a reference work. In 1712 Frederick II scored an incredible coup: he purchased the collection of count Anton Günther II von Schwarzburg-Arnstadt (1653-1716). We have to take you up on that later.

The representative rooms. A cabinet, made c.1680. Photo: KW.

Little later, this cabinet from Augsburg was made. Probably it did not serve for storing coins but other small objects you can see in the exhibition of the Cabinet of curiosities.

Asiatica in a showcase. Photo: KW.

Anyway, the Cabinet of curiosities! If we had not been so pressed for time we would have been lost here! So much to see and no end. As always we limit ourselves to a description of the numismatic objects – making one exception.

Cup from Augsburg in a hare shape. Photo: KW.

This cup from Augsburg shaped like a hare – isn’t it cute?

This is a coin cup. Photo: KW.

There was a coin cup …

An enamelled medal on Frederick I of Prussia from Wermuth’s hands. Photo: KW.

… a baroque ‘coloured coin’ (and now, who dares still to lament on the degeneration of modern numismatics?) …

Object made of ivory with miniature medallions. Photo: KW.

… and an object made of ivory with the portrait of Frederick, Duke of Saxe and Altenburg – probably Frederick II comparing the nose of this man in ivory with that on coins.

Wax portrait of the duchess Elisabeth Sophie (1619-1680). Photo: KW.

The wax portraits impressed me deeply, they were so lively even more than modern photos, capturing the aristocratic greatness of these personalities. These portraits made of coloured wax, velvet, silk, tulle, and glass stone were made by a woman named Anna Maria Braun around 1675/80. This Anna-Maria Braun was one of the very rare female medallists who are known by name although I was not able to detect a photo of any of her medals.

Christof Boehringer as the hero of the German fairy tale The Star Money under an arch of coins. Photo: KW.

And with that object, finally, we have reached the coin exhibition! Showpiece is an enormous triumphal arch from which coins and medals pour. It is really made for photographing! Looking more attentively one notices that no galvanos are applied on this arch but real coins. Gotha is just so abundant of numismatic treasures that they can let them rain – so to speak – on the visitors.

Let’s review a small choice of particularly precious objects on display in the showcases nearby the triumphal arch. We link these items with some details of the collection’s history.

Gnadenpfennig with enamelled framing showing a portrait of Ernst I The Pious, by Wendel Elias Freund, c.1653. Photo: KW.

As we said initially, Ernst I (1601-1675) received a part of the Ernestine Cabinet of curiosities comprising, among other things, 516 coins and medals. It is really remarkable that this collection in Gotha exists, but particularly, how precisely we can describe all details of how it came to existence thanks to the sources at our disposition! 781 pieces were purchased between 1653 and 1656. According to the list the emphasis was put on antiquity.

Medal in occasion of the death of Prince John William of Saxe-Gotha-Altenburg (1677-1707) at Toulon, 1707 by Johann Christian Koch or Maria Juliana Wermuth. Photo: KW.

The son of Ernst I, Frederick I (1646-1691), was a passionate collector, too. He considered himself to be a baroque aristocrat, and he attempted to conceal his loss of power – provoked especially by the division of his father’s estate – by increasing his representation. Part of this conception of oneself was a coin collection. The duke enjoyed making an inventory of his coins and arranging them in order, as we learn form his diaries.

Medal in occasion of the reconciliation of Ritter Franz von Sickingen with emperor Maximilian I. Silver, gilded, 1518. Photo: KW.

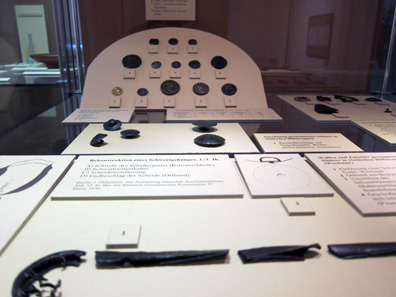

Frederick I passed on this pleasure in numismatics to his son Frederick II (1676-1732). In 1712, Frederick II succeeded in acquiring the collection of Anton Günther II, ruler of Schwarzburg, a collection that was known all over Europe. The latter had gathered this impressive collection with the help of the Parisian numismatist Andreas Morell (1646-1703). In 1709, though, Anton Günther suffered financial embarrassments. The emperor wished to appoint him Prince of the Holy Roman Empire, but immediately the dukes of Saxony intervened occupying the residence city of Arnstadt in order to assert their feudal rights. In the end they settled for money, but for much more money than Schwarzburg could bear. Then Frederick made Anton Günther a “generous” proposal: he offered to pay 100,000 talers for the collection that comprised 2,781 gold coins, more than 1,000 Greek and almost 7,000 Roman coins, over 6,000 (sic!) brakteats, not to forget 2,000 German and European pieces, and 4,500 medals.

And then, naturally, the heirs of Frederick II kept purchasing material. However, it would be too long a list if we tried to enumerate all acquisitions. Those interested in this topic should read the brand-new book ‘Gothas Gold’ where Martin Eberle describes the history of the collection in all details.

If you want to order that bibliophilic book, please click here.

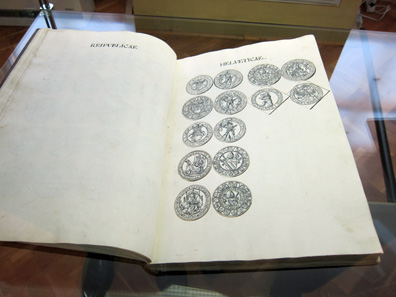

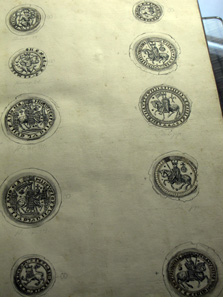

Frederick II ordered the drawings in these gorgeous volumes to be executed manually(!). Photo: KW.

By the way, Frederick II did not spend all his money on coins. He ordered these incredible illustrated books, too. The images were not printed but drawn by pen and ink scumbled with the brush to reproduce the coins with the utmost precision.

Brakteats from the Gotha Collection. Photo: KW.

This photo shows the high quality of the drawings.

A glance into the research library in Gotha. Photo: KW.

And don’t you believe this was all Gotha offers in numismatics. Unfortunately you are admitted only accompanied to the recently restored coin cabinet placed inside of the research library in Gotha.

And this is the coin cabinet. Photo: KW.

During the congress we were able to cast a glance at that baroque room. After having acquired the Schwarzburg Collection Frederick II decided to separate the coins and medals from the Cabinet of curiosities and to establish a prestigious coin cabinet in the east wing. He was moved to do so by practical reasons above all. Now visitors could see the coins without passing the duke’s private chambers. Frederick II, hence, had his peace and nevertheless the early modern globetrotters spread the fame of his collection.

No, it’s not possible to attribute the emperor busts to single rulers. Some portraits exist in various forms, others, however, show simply no similarity to any of the twelve Caesars. Photo: KW.

In the coin cabinet fifteen cabinets stored the coins in the upper part, below the relative books. On top of these cabinets ancient objects were allegedly displayed, which are lost, though.

Saskia and Christina Höhn in the Gotha coin cabinet. Photo: KW.

At the head end a statue of the founder of the coin cabinet, Frederick II, was placed. However, unfortunately the statue is lost too.

Catalogue of the Gotha Collection. Photo: KW.

In compensation we have still the impressive catalogues of the collection written by hand.

A glance at a showcase dedicated to the regional history and archaeology. Photo: KW.

We have, by far, not reached the end of Schloss Friedenstein’s range of numismatic treasures. Those who visit the history exhibition will see coins all over again. There, for instance, you can see a couple of Roman coins in the archaeological section …

Pay list of the actors of the Eckhoff theatre at Schloss Friedenstein. Photo: KW.

… or the pay list of the famous Eckhoff theatre at Schloss Friedenstein. Its stage machinery has completely survived since the baroque time.

What did I say first? Three to four hours? Well, to be honest, we wished we had the double of time at our disposition in order to appreciate all these treasures adequately. So, better take off a whole day for Schloss Friedenstein. It is worth it – and the same goes for Gotha’s magic old town!