by courtesy of Heiner Stotz, LHS Numismatics

A unique Electrum stater from Cyzicus minted in 405/4

In 407 the Spartans sent Lysander to command their forces in Asia Minor: he had great success, and in the very same year crushed the Athenian fleet at Notium. Such a great victory appeared disturbing to the Spartans, and as a result, in 406, they replaced the triumphant Lysander as admiral by Callicrates; he, however, almost immediately was defeated and lost his life at the Arginusae. Lysander then returned and defeated the Athenians at Aegospotamoi, giving Sparta supremacy in the Aegean. This was to the advantage of a number of oligarchs living in the cities of Asia Minor because they were then able to oust their democratic opponents from political office – of course with a little help from Lysander – and to take over control of their cities.

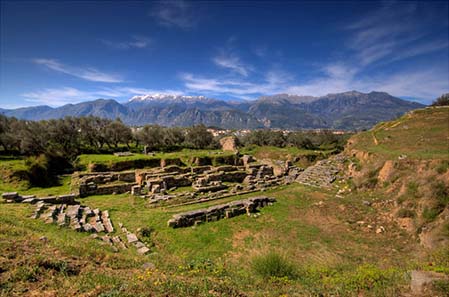

Ruins of the ancient theater of Sparta, in the background, the Taygetos Mountains. Photo: Nickthegreek82 / Wikipedia.

Ephesus had revolted against Athens no later than 412 and had succeeded in remaining independent despite Athenian attacks, thus Lysander made it his headquarters. This was more than beneficial for Ephesus: Lysander’s presence spurred economic growth, especially since he had the harbor enlarged and attracted trading vessels from all over the ancient world to the city. The Ephesians rewarded these efforts with their unswerving loyalty to Sparta. Cnidos had also renounced its membership in the Attic-Delian league in 412, and had beaten back all attacks from the Athenian fleet. Lysander established a naval base there in 407. The same occured at Rhodes, which had defected from Athens in ca. 408/7. However, Byzantium, Cyzicus, Lampsacus and Iasus remained loyal to Athens and had to be captured by Lysander more or less by force after the battle of Aegospotamoi. Samos remained true to Athens the longest. Lysander was only able to take over the island in 404, and for that reason the citizens had to accept a government he imposed on them.

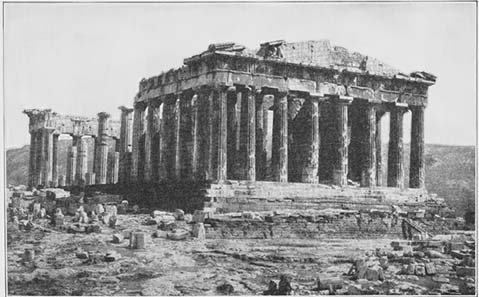

The Athenian Parthenon was not only the place, where the treasure of the Attic-Delian league was kept. The building was also paid with money owned by the league. Photo of the 19th century.

Obviously, all these cities stopped paying tribute to Athens. This involved enormous amounts. Ephesus had paid between 6 and 7 1/2 talents; Cnidus between 3 and 5; Rhodes up to 10; Byzantium between 15 and 21; Cyzicus 9; Lampsacus 12; and Iasus between 1 and 4. Samos did not contribute silver, but had to make its fleet available to Athens. These cities could now use all this silver to mint their own coins. It is easy to understand that they choose a theme that celebrated Lysander as liberator.

Herakles facing the crucial decision between Virtues and Vices. Painting by Annibale Carraci, ca. 1596. Wikipedia.

Though Lysander was not a member of either of the two Spartan royal families, he claimed to be descended from Heracles, and, thus, the “freed” cities choose a motif, which showed Lysander’s ancestor performing his first heroic deed. Herakles was the son of Zeus by Alkmene, who bore him as one of two twins, the other being Iphikles, son of her actual husband, king Amphitryon of Thebes. Hera was furiously jealous of this and sent two snakes to destroy the infants. Woken by his half-brother’s cries, Herakles had crushed both snakes by the time Alkmene and Amphitryon burst into the room. This feat proved him to be Zeus’ true child, who managed to free himself and others from evils caused by envy and jealousy. The cities, which minted coins with this scene, did so because they saw an analogy in the efforts of Lysander: he freed them from political suppression by Athens.

Samos. Tridrachm, ca. 405/4. The infant Herakles strangling two serpents. Rv. Frontal lion’s mask. 11,29 g. Barron 1b (this specimen). From Leu Auction 81 (2001), 283.

Tridrachms bearing this scene from Byzantium, Lampsacus, Ephesus, Samos, Iasus, Cnidus and Rhodes have been known for a long time, and are part of the so-called SYN-alliance series. Hektes from Cyzicus with the identical type also exist.

Cyzicus. Electrum stater, ca. 405/4. The infant Herakles strangling two serpents; below, tunny fish swimming to r. Rv. Quadripartite incuse square. 16.15 g. Unique. From Leu Numismatics Ltd. Auction 95 (2005), 649.

But the first known electrum stater of Cyzicus showing the infant snake-strangler Herakles came up for sale in Leu Numismatics Ltd. Auction 95, and must be connected with the coins from the SYN-alliance series for stylistic reasons.

Of course we know that our date for the SYN-alliance series is not accepted by everyone. J. Barron, Two Goddesses in Samos, Studies Price, pp. 23-27, envisioned different historical context. He interpreted the coins as numismatic testimony to an anti-Spartan alliance, which came into being after the victory of Conon at Cnidos in 394 BC. We have, however, preferred to follow the argumentation of S. Karwiese, Herakliskos Drakonopignon, NC 1980, 1-27, which seems to us to be more logical.

Emblems are a typical art form of the Renaissance period and are composed of three elements: a motto, an illustration and a device. Here the motto reads: In cunis iam Iove dignus (= worthy of Iupiter even in the cradle).

By the way, inspired by ancient coinage, Renaissance artists used the picture of the snake-strangler Herakles as an emblem, a kind of rebus used by the educated to express the belief that the true greatness of an outstanding personality would already reveal itself in the early childhood.