by Ursula Kampmann

translated by Teresa Teklic

May 25, 2017 – Malicious gossip in my family has it that I studied Ancient History for one reason only, and that is to find out how much of the historical novels that I devoured in my childhood were actually true. I deny such allegations, of course, even if Sagunto will always be linked to a novel by Hans Baumann for me. The title was “Ich zog mit Hannibal” (“I marched with Hannibal”) and the book was about an old man, who, after long years of Roman enslavement, returns home to dig a well. It is meant to enable new life in the ruins of Sagunto. He meets two children, whom he tells about the ruthless power games of the politicians who are to blame for the fall of this city and all the people that used to live in it.

Switzerland. Silver medal by Genevan medalist Jean Dassier on the Siege of Saguntum, 1740-1750. Obverse: personification of Sagunto under the crashing walls. Reverse: Roman senate in session. From RBW collection and CNG auction sale 364 (2015), No. 392.

To me, Sagunto will always showcase how the interests of the powerful are ruthlessly pursued on the back of the common people. The indifference displayed by the Roman senate towards the siege of the city and its impertinence after the conquest is an injustice that cries out to heaven. Just like all the people who were massacred by the Carthaginians.

Arse-Saguntum. Bronze, ca. 200-150 BC. From CNG auction sale 353 (2015), No. 1.

But let’s begin at the beginning. After the end of the First Punic War, Carthage needed to find new trade routes, if it wanted to pay the Roman reparations on the one hand and compensate the loss of its emporiums on Sicily, Sardinia, and Corsica. They sent 26-year-old Hannibal to Spain, which promised rich metal resources. He began to build a new trade empire and looked for allies among the local Celtiberians. He didn’t win over the Saguntans. On the contrary. From their refuge castle they conducted raids against Hannibal’s allies.

Arse-Saguntum. Bronze, ca. 200-150 BC. From CNG auction sale 316 (2013), No. 5.

Of course Hannibal didn’t put up with that. After all, it was his job to protect the allies. So he moved against the Saguntans, which then played the Roman wildcard. They were allied with Rome, so Hannibal had better up and leave real quick. Which, of course, he did not. He laid siege to the city and a whole eight months on top of that. After he’d taken the city, he had all inhabitants massacred or enslaved, and razed the city to the ground. Meanwhile, Rome did nothing. Only after the Siege of Saguntum did they bother to send a delegate to Carthage and demand Hannibal be extradited to Rome for punishment. The Carthaginian politicians refused, – and Lo and behold! – Rome declared war.

Arse-Saguntum. Bronze, ca. 150-100 BC. From Huntington collection and CNG auction sale 316 (2013), No. 7.

There are libraries on the question of war guilt. Did Hannibal have the law on his side because the city was on Carthaginian territory according to the Ebro Treaty? Or was he an aggressor because he was raising means in Spain to finance the next war against Rome?

Who still cares these days? And for the Romans it only mattered as much because the gods lent their support exclusively for just wars. (You won’t believe to what lengths the Roman constitutional law went to justify all these wars in front of the gods.) Just or unjust, it must have mattered very little to the people of Sagunto.

Today’s historians have realized (or should at least have realized) that there is seldom a single culprit behind a war but most often numerous interests, several reasons, and one trigger. Rome was pursuing its expansionist agenda, Carthage wanted to conduct profitable business. Both were not possible simultaneously. And so began the Second Punic War.

Now you must understand why I wanted to see Sagunto and feel the genius loci…

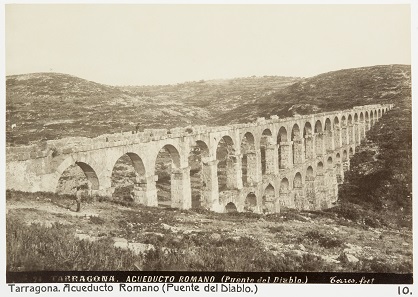

The devil’s bridge or “Puente del Diablo”, as the Roman aqueduct of Tarragona was called. Photo: Johanna Kempes from 1895.

Wednesday, March 22, 2017

We start out in Tarragona at a reasonable time. Or, let’s say not quite yet. First we want to see the Roman aqueduct, which is supposed to be a very special sight. The Les Ferreres Aqueduct, also called “Puente del Diablo” (“Devil’s Bridge”), is not only the best preserved but also the biggest aqueduct in Catalonia. You should think that this would make it easy to find, especially since we’d already seen it from the highway on our arrival in the city. So theoretically all we needed to do was get back on the highway.

With that logic we grossly underestimated the large number of possible highways with very different on-ramps. And took the wrong one, of course. We see many things but no aqueduct. so that after a half-hour odyssey we decide that we’ve seen too many water pipes in our life, including Roman ones, to care enough about this one. And a bigger attraction calls: Sagunto, the city in which the Second Punic War began.

Tortosa is on the Camino de Santiago, though not on the traditional Camino Francés. Photo: KW.

But we are tempted to turn into Tortosa. No idea why. But somehow the name promises something special, a certain mystery. And the city is trying. Road signs direct us to a car park, on which carpenters and construction workers are enthusiastically working, fixing things here and there. A more than friendly attendant practically jumps out of his attendant’s hut to hand us a map of Tortosa. With its help (and numerous road signs) we indeed manage to find the old town rather quickly.

Dertosa-Tortosa. Tiberius, 14-37. Bronze. From CNG auction sale 76 (2007), 1016.

There isn’t much to say about Tortosa. It has Ibero-Celtic origins and the Ebro flows nearby. First the Romans settled her, later the Muslims. In 1148 Berenguer IV took the city and called it a crusade. And that’s about it, more or less.

Kingdom of Valencia. Juan II, 1458-1479. Terc de croat, Tortosa. From Aureo & Calicó auction sale 259 (2014), No. 585.

Coins, however, were minted aplenty in Tortosa. Especially when it belonged to the Kingdom of Valencia.

Kingdom of Valencia. Senyal, Tortosa, around 1470. From Aureo & Calicó auction sale 259 (2014), No. 794.

Only once you start looking into coins do you realize that Spain is not that neat entity as which we tend to perceive it, but that prior to the Catholic kings the confusion between counts, cities, and monasteries equalled that of the Holy Roman Empire.

Aragon. Pedro III, 1336-1387. Florin, no date (1369-1377), Tortosa or Valencia. From Künker 129 auction sale (2007), 281.

Tortosa is interesting for the history of medieval coinage in Spain in so far as it was the place in which Pedro III of Aragon signed a treaty with the Corts Valencianes, the main legislative body, which defined the weight and fine content of the new coins, modelled on the florin. Whether the tower on the coin is a mint mark for Tortosa or Valencia is subject to dispute among Spanish numismatists and we are certainly not going to barge in here.

A pretty building in the style of Modernismo. Photo: KW.

So, where were we? Right, Tortosa. It has a pretty old town with a pretty cathedral and several pretty buildings from the period of Modernismo, but after Tarragona we’re spoiled. We’re not even impressed by the gate through which once the pilgrims on the Camino walked, and which still features a gigantic Santiago (St Jacob) on the one, and a Saint Christopher on the other wall. So Tortosa cannot keep us longer than an hour and a half. It’s a pity because the city fathers have gone to such lengths to prolong the duration of the tourists’ stay in their city.

When we were still in Tarragona we booked a nice hotel by the name of Puerto di Sagunto. Our satnav lady finds it without problems. And that’s good. Because we, on other hand, would never have found it! We imagined that the hotel would be somewhere in Sagunto. But it really was in the industrial harbour. The balcony we’d booked (and which naturally came at a surcharge) had an unobstructed view of the backside of an industrial building. But the rooms are okay, and the location not as bad as we’d first anticipated.

Right next to the train station: the glass covers ruins. Photo: KW.

After we have brought our luggage to our rooms, we get in the car once more. After all we want to see the excavations of Sagunto! Lonely Planet promises a huge excavation site. If only we could find it! We park right next to the train station and indeed discover a piece of Roman road covered by glass. But where is the stupid refuge castle, in which the people of Sagunto were able to hold out for eight months? Well, if there are no road signs, we’ll have to rely on our common sense. Refuge castles are supposed to be somehow elevated, so we climb the narrow roads.

Right in the old town: the Roman theatre. Photo: KW.

In Spain, unlike in Italy, Greece, or Turkey, excavation sites are not located outside of the modern cities. On the contrary, they are right in the city centre. So we literally stumble upon the ancient theatre while looking for the castle hill. Though ancient theatre isn’t quite accurate. It has been remodelled so that the Saguntans can still see concerts and theatre performances here. It’s interesting that the remodelling was possible considering that the theatre was declared the first “National historic monument” in 1896.

Castle hill. Seen from this side, it’s much more impressive than the first look we got. Photo: KW.

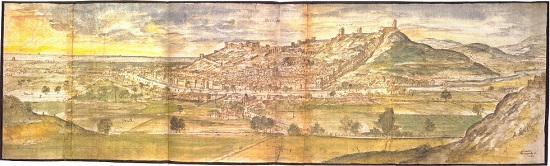

The refuge castle of Sagunto was first settled by the Celtiberians. The Saguntans withdrew to this place when Hannibal and his troops laid siege to them, and it definitely wouldn’t be the last time that the population sought refuge within the confines of these walls.

Castle hill of Sagunto in 1563. By Anton van den Wyngaerde.

In 929/30, the now Muslim castle Abd-ar Rahman was taken. From 1098 to 1102, the infamous Cid ruled the castle hill. Jaume I incorporated Sagunto into the Kingdom of Valencia in 1238 and that’s why, in the 13th century, the Christians lived in the castle on top, while the city below was still settled by Muslims.

The cave system on the foot of the castle hill once belonged to a Jewish cemetery. Photo: KW.

A Jewish cemetery, which was put into place in the cave system on the foot of the hill, testifies to the large Jewish community which lived here in the Middle Ages.

Philipp II of Spain expanded the castle of Sagunto. Photo: KW.

But we are not yet done with the sieges. In the War of the Spanish Succession, in the war against Napoleon, time and again the defenders withdrew to the castle. And I read somewhere on a sign that individual towers continued to serve as hide-outs for snipers in the Spanish Civil War.

The steep climb to the castle. No wonder it took Hannibal so long to capture it. Photo: KW.

The sky is grey, the climb steep, the excavation very different from what I’d expected: First I am disappointed because so little has remained from Roman times. And then the genius loci still takes possession of me. I’m sitting on the very top. The wind is blowing, the sun just started to burn down on me, and I indulge in daydreams, imagining how it must have been when, more than 2,000 years ago, the city’s inhabitants looked down to Hannibal’s huge army and asked themselves what the hell was taking the Romans so long…

The entrance to the Jewish quarter. Photo: KW.

Speaking of valleys. When we descend the hill, we’re hungry. Bad idea! Even fewer bars are open in the afternoon in Sagunto than in Tarragona. It seems to me that somehow Spain and hunger don’t go well together. When the Spanish eat, I’m asleep, and when I want to eat, the Spanish are not hungry and thus don’t open any bars. Rescue came in the form of a pastry shop. Apparently sweet always works in Spain. Well, it’s not a culinary highlight, but it’s filling. And as a precaution we also already buy food for dinner, after all the industrial harbour of Sagunto might not be the best location to find a good restaurant…

I almost forgot, one more thing if you like music: Joaquín Rodrigo, the composer of the magnificent Concierto de Aranjuez, was born in Sagunto. If you want to hear it… here it is…

Does Lonja de la Seda ring a bell with you? For me, the most fantastic thing we’ve seen on our entire trip. It’s a commodity market for silk, a virtual temple of trading. It’s in Valencia, and that’s precisely where our next stop will be.

All episodes of the numismatic travelogue “To Spain!” are available here.