February 23, 2017 – The world’s earliest paper money takes its place alongside the most technologically sophisticated new note in a new permanent gallery at the Bank of England Museum. The Banknote Gallery at the Museum presents the story of the banknote, from its earliest days when paper money was largely mistrusted, to the new £5 note, packed with security features, minute, historically significant designs and printed on polymer rather than paper.

Filled with original drawings, artwork, designs, notes and sketches from the Bank’s collection, the new Banknote Gallery opened on 7 September 2016 at the Bank of England Museum in the Bank’s Threadneedle Street building. The new polymer £5 note launched a week later, on 13 September. Entry to the Museum is free.

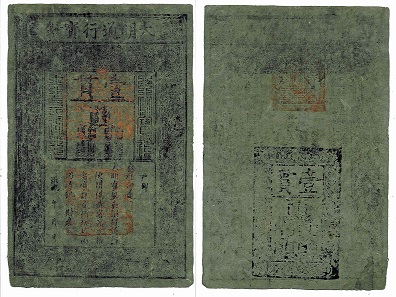

One of the very earliest paper banknotes from Ming dynasty China. Photo: © Bank of England Museum.

The new gallery builds a clear picture of how banknotes have changed since the Bank was established in 1694. Among the highlights are the earliest paper notes from Ming dynasty China and the ‘running cash’ notes – as old as the Bank of England itself – accepted as payments in place of a pile of gold.

The gallery also includes the earliest Bank of England notes from the end of the 17th century and classic designs such as the ‘white fiver’ which lasted for 100 years.

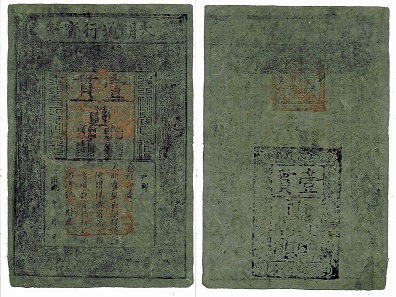

19th century ‘Flash note’. Photo: © Bank of England Museum.

As soon as banknotes appeared, so did forgeries; the story of banknote design is paralleled by an alternative history of the development of counterfeiting. Since its foundation, the Bank of England has been in a constant battle to stay several steps ahead of forgers; even the simple black and white notes of the 18th century contained a whole battery of subtle security features, including complex watermarks and minute secret marks that helped Bank clerks identify genuine notes from forgeries. Many forgeries ended up at the Bank of England.

Among those forgeries on display are brilliantly plausible notes which are surviving evidence of Operation Bernhard, the Nazi plan to flood and ruin the economy of the British Empire during the Second World War. Created by prisoners at Sachsenhausen concentration camp, the notes were intended to be dropped by plane over Britain, picked up and used by members of the public. While this never happened, the Bank was forced to withdraw all notes over £5 and re-design the £5 note after the forgeries began to appear in circulation in Britain.

Also on display are earlier forgeries, many of whose creators were punished by hanging. Among these is a £5 note altered to a £50, which was discovered when it was used to buy a cow at a country fair in 1850. During the Bank Restriction Period in the early 18th century, hundreds of forgers received the death penalty for counterfeits of Bank of England notes.

The gallery includes a wealth of beautifully intricate original design artwork, much never previously displayed, which illustrates the complete process of creating a note. This includes material by Banknote designers including Daniel Maclise, Harry Eccleston, Stephen Gooden and Roger Withington, initial design sketches, detailed master drawings, test prints and printing plates for scores of different notes, presenting a roll call of characters that have found their way on to banknotes, as well as the changing face of the Queen and how the Bank’s Britannia emblem has evolved.

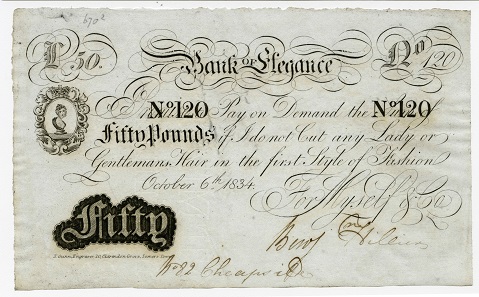

The inimitable note. Photo: © Bank of England Museum.

And alongside the designs which became Bank of England banknotes are all sorts of designs submitted to the Bank in the early 19th century after it announced a competition to make the ‘Inimitable Note’ – a banknote that could not be copied.

Elsewhere, the gallery follows the journey of a banknote from creation to destruction and eventual recycling.

The gallery also includes large, historic piece of design machinery – a geometric chuck lathe. Built in 1905 and in use until the 1980s, the machine created the ‘Spirograph’ patterns that decorated the Series A (1928) and Series C (1960s) banknotes. A combination of art and mathematics, the lathe generated an almost infinite number of complex patterns, virtually impossible to copy exactly, either by hand or machine.

The Bank of England’s newest note, the polymer £5, which launched on 13 Sept 2016. Photo: © Bank of England Museum.

The inspiration for the new gallery is the Bank of England’s newest note, the polymer £5. The most sophisticated note ever designed, its thin plastic material also makes it the strongest, safest, longest lasting (21,835 damaged paper notes had to be replaced in 2015) and cleanest. Within its design are a see-through window, a gold and silver Elizabeth Tower and a portrait of Winston Churchill. The Churchill illustration is based on the famous 1941 photograph of Churchill by Yusuf Karsh, known as ‘The Roaring Lion’. His slightly indignant expression may be put down to the fact that the photography sitting was very rushed and he had just had the cigar that he’d been tetchily smoking whisked away from him by Karsh.

The new £5 will be followed in summer 2017 by a polymer £10 note featuring Jane Austen and, by 2020, a polymer £20 note featuring JMW Turner.

Curator of the Bank of England Museum, Jennifer Adam, said, “The new polymer £5 note begins a new era of banknote design and technology and gives us the perfect opportunity to show off the most beautiful, significant and, in some cases, surprising notes in the Bank’s collection. The pairing of notes from the 1690s with the new note shows how far we have come, but while the original notes may appear simple in comparison, they were packed with design tricks designed to outwit counterfeiters. At the outset, banknotes had to win over a sceptical public that could not see the link between a piece of paper and a pile of gold. I hope that the new gallery will make people regard the note in their pocket differently, as a beautiful, innovative work of art, before they have to part with it.”

For more information please visit the website of the Bank of England.