By Ursula Kampmann

July 3, 2014 – From June 13 to 15, 2014, the annual meeting of the Association of German Coin Dealers was held. It was hosted by Heinz-W. Müller and other colleagues from the Düsseldorf area like Münzhandlung Ritter and the expert on medals, Auktionshaus Winter. Heinz Müller had made an incredible effort to make all those participants that had never been to the Bergisches Land before realize how beautiful this area is. And his attempt to share his enthusiasm proved successful. Here we would like to introduce you to the numismatic side of Burg Castle on the Wupper river, family seat of the County of Berg.

Burg Castle, a slightly idealized version of it. Photograph: UK.

At some point during the 11th century, a noble family managed to establish itself as counts ‘del Monte’, of the caste. They built their castle on the Wupper river around 1150, according to archaeological testimonies.

Engelbert I of Berg, as Archbishop of Cologne, 1216-1225. From auction sale Münzen und Medaillen GmbH 28 (2008), 372.

The most famous count of the house of Berg was Engelbert II that held a churchly office, like many younger sons. He had built his career in early life already: in 1216, when he was just 30 years of age, hence at the canonical age for becoming a bishop, Engelbert was appointed the most important church prince, Archbishop of Cologne and hence imperial administrator for Frederick II who could not wait to return to his beloved, sunny Sicily.

The statue of the count’s archbishop at the entrance to the castle. Photograph: UK.

Only two years later, Engelbert’s brother Adolf II, Count of Berg, died. His survivors included no male heirs. Instead the dear family appeared at the stage immediately. The relatives would have loved nothing better than to accept the inheritance, mainly because they were entitled to it, strictly speaking: the heir to the throne of the Duchy of Limbourg had married the only daughter of late Adolf, Irmgard, and thus was inheritable, according to the customs of that era. Engelbert pushed his claim, though. As Archbishop of Cologne, he possessed the greater resources, it was as simple as that.

The assassination of Engelbert. A historicizing painting from the 19th century in the ceremonial hall of Burg Castle. Photograph: UK.

What a pity that the former could not just let go.Walram IV of Limbourg organized another relative, Count Frederick of Isenberg who, with the aid of some other men, tried to take the archbishop captive. Engelbert, however, put up such great a resistance that the attackers killed him. Hard luck. For both of them. Engelbert was declared a saint (albeit not officially) and Count of Isenberg was arrested upon his return from Rome where he had convinced the pope of him not having intended to make the archbishop a martyr in the first place. The pope may have believed him. But the citizens of Cologne did not. The broke the murderer of their archbishop on the wheel.

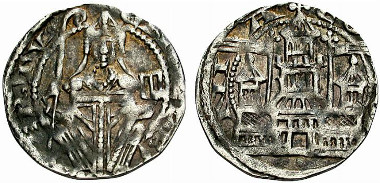

County of Berg. Adolf V, 1259-1296. Pfennig, Wipperfürth. From auction sale Künker 229 (2013), 5686.

Only one person benefited: Irmgard and her Henry of Limbourg inherited. They provided the County of Berg not only with a new ruler but also with a coat of arms: the Limbourg’s lion became the coat of arms of the County of Berg.

Something nobody could have foreseen was that Irmgard died already in 1283, childless, which made the inheritance wheel turn again. As many as ten legal heirs hoped to get their share, including one of the many Adolfs the house of the counts of Berg had produced. If he is to be called Adolf V, VII or rather VIII seems to be left up to the author. At any rate, we refer to the Adolf who died in 1296 and who was granted the minting right by King Rudolf on March 26, 1275.

The Battle of Worringen. Diorama of pewter figures at Burg Castle. Photograph: UK.

Strictly speaking, he had already sold his claims to the Duke of Brabant. But the Archbishop of Cologne, Siegfried of Westerburg, sniffed a chance, as territorial lord and rejoicing third party, to get his hands on the vacant fee re-allocate it again. The logical consequence was the Battle of Worringen that took place in 1288 during which the very archbishop was taken prisoner. He not only had to pay ransom money amounting to 12,000 mark silver, but also to abandon the Bergisches Land for good. Plus, his standing in his own city was weakened which accelerated the process of Cologne becoming a free imperial city.

Adolf VI, 1308-1348. Turnose, Wipperfürth. From auction sale Künker 115 (2006), 2568.

The last ruler of the Limbourg family was Adolf VI, a loyal supporter of Louis of Bavaria. He, too, died without leaving any male heir. And so, yet another time a brother-in-law came into an inheritance, Gerhard of Jülich-Berg who had married the sister of the deceased.

At this point, we skip a number of intricate inheritances but mention casually one count of Berg being an important advisor for Charles IV which was reason enough for the latter’s son Wenceslaus to elevate the County of Berg to the rank of a duchy. This is of importance only for the fact that it made Düsseldorf a residential city, and the counts of Berg used Burg Castle only sporadically for hunting and ceremonial purposes.

Betrothal of Mary of Jülich-Berg and John the Peaceful of Cleves-Mark. Historicizing painting at Burg Castle. Photograph: UK.

So the engagement of two children was celebrated, of the heirs to the dynasties of Jülich-Berg and Cleves-Mark that led to the formation of the United Duchies of Jülich-Cleves-Berg.

John III, 1511-1539. Albus 1513. From auction sale Künker 143 (2008), 1975.

John, who was given the nice nickname ‘The Peaceful’, assumed control over Jülich, Berg and Ravensburg and received Cleves and Berg as well when his father died in 1521. That made him the most powerful regent in Western Germany.

The battery tower. Photograph: UK.

Burg Castle had another, short, appearance during the 39 Years’ War, but decayed in the course over the centuries, served as a stone pit and a factory, until castles came (back) into fashion in the 19th century. Thus, on August 3, 1887, a society was founded that was to bear the beautiful name ‘Schlossbauverein’ soon. After all, Haut-Koenigsbourg, Wartburg and even Schwanstein Castle were kept in mind when making a plan to create a highly memorable testimony to the German Middle Ages. William II, who fostered a huge interest in history, visited the construction site and provided money – and he was not the only one.

The coin dealers marvel at the state rooms of Burg Castle that were built in the 19th century. Photograph: UK.

Hence, since the 19th century, the Bergisches Land has a great tourist attraction – Burg Castle that also has some numismatic goodies to offer.

Hoard of coins discovered during construction works in 1952. Photograph: UK.

First of all, there is a hoard that was discovered during construction works at Burg Castle in 1952. It is tempting to link the 508 medieval denarii with one of the lords of the castle – after all, Count Adolf III had died in the crusade in Egypt in 1218. So he was denied any chance of retrieving his coins ever again. But the not quite so romantic numismatists point out that the 508 pfennige cannot be considered a princely fortune and, consequently, this hypothesis has no basis in fact.

The Coin Cabinet. Photograph: UK.

There is likewise a coin collection at Burg Castle, albeit it only consists of the poor remains of the old collection and some acquisitions of recent. The impressive collection of the 19th century was destroyed in a fire and in its aftermath, respectively. But still, there are some things to marvel at, in this hall.

Klippe coins, minted during the siege of Jülich. Photograph: UK.

Like, for example, klippe coins that were minted during the siege of Jülich in 1610.

Scaes of the company Mittelstenscheid from Lennep. Photograph: UK.

In addition, the museum possesses a nice collection of scales. Hardly a surprise for there was a center for the production of coin scales in the Bergisches Land since around 1750. The blooming period of this branch of industry came to an end when the minting technology improved considerably around 1840 to the effect that scales were no longer needed in order to check if a coin was clipped.

Medieval cupboard for objects of value. Photograph: UK.

Let us conclude our numismatic tour around Burg Castle with a medieval safe that was made in the 14th century in all probability. That this furniture is a real cupboard is remarkable because the people of that era basically only knew chests for storing the household effects – including the valuable goods.

Christoph Raab, President of the Association of German Coin Dealers, presents a representative of the Schlossbauverein with an abacus as an addition to the collection. Photograph: UK.

For the numismatic collection to thrive, Christoph Raab, President of the Association of German Coin Dealers, donated an abacus on behalf of all visitors that may well become part of a new exhibition. Plans are already being made but they are not very likely to be realized soon because Burg Castle is privately maintained for until the present day. The Schlossbauverein Burg an der Wupper procures 85% of the operating costs out of its own pocket!