by Ursula Kampmann

August 8, 2013 – Roughly 80,000 years of the history of civilization are presented in the Landemuseum Stuttgart since 2012 in his new permanent exhibition. A substantial part of it is in fact related to numismatics as we have noticed at our recent visit.

View inside the exhibition, section Early Neolithic. Photograph: KW.

And 80,000 years it truly is. The most ancient traces for human settlement of Wuerttemberg come from the vicinity of Bad Canstatt and most likely are approximately 240,000 years old. The Neanderthals settled in the great caves of the Swabian Alps during the last ice age and created objects by whose ageless beauty the modern viewer is still impressed.

Spiral arm rings from the hoard find of Ravensburg, 1,900-1,600. Photograph: KW.

Nevertheless, the first evidence of money dates to a younger period of time – Wuerttemberg is no exception from the rule –, i.e. to the turn from the Copper Age to the Bronze Age.

Fragments of a Cypriote copper ingot from the hoard find of Oberwilflingen. 14th / early 13th cent. B. C. Photograph: KW.

Numerous hoard finds with standardized metal objects have been discovered, including spiral arm rings, ribs (bars) as well as fragments of a Cypriote copper ingot.

Complete copper bars – not from Stuttgart but from the Old Museum in Berlin, 2nd millennium B. C., from the sea between Turkey and Cyprus. Photograph: KW.

Copper from Cyprus has been found in the entire Mediterranean region, while Wuerttemberg, admittedly, is a quite exotic find-spot for Cypriote copper. One would expect these huge bars, weighing roughly 25 kilograms in the shape of an oxhide, rather to be part of a ship sunk near the coasts of the eastern Mediterranean.

Two Langquaid Type axes. Photograph: KW.

And there are of course the different, standardized axe types in Wuerttemberg, like the ones shown here belonging to the Langquaid Type, that have been found together with approximately 100 ribs.

Bronze hoard consisting of 110 items. Photograph: KW.

The interpretation of these hoard finds – perhaps it was a smith’s metal cache that has been entrusted to the ground for safety reasons, or a small treasure piled up by a rich man thousands of millennia ago, as a kind of nest egg – remains for everyone to decide. Needless to say, there are no extant written sources from this period of time.

Celtic coin following the Macedonian model, 2nd-1st cent. B. C., found near Nagold, Calw district. Photograph: KW.

On a less slippery ground we are with the gorgeous Celtic coins exhibited in the Landesmuseum. After all, Wuerttemberg was a center of the Celtic culture. Just think of the Heuneburg with its wall built after Mediterranean models. The Ruler of Hochdorf, whose tomb was discovered in 1978, likewise is a good example for the wealth local potentates could accumulate given they had good connections with the south.

Iron bar from a hoard dating to the 2nd/1st centuries B. C., Uttenweiler, Biberach district. Photograph: KW.

The bars, however, looked slightly different by then. Iron had become important and was traded in the shape of pointed ingots weighing between 5.5 and 7.5 kilograms.

A showcase with Celtic coins. Photograph: KW.

An entire corner of the Celtic section is devoted to coining.

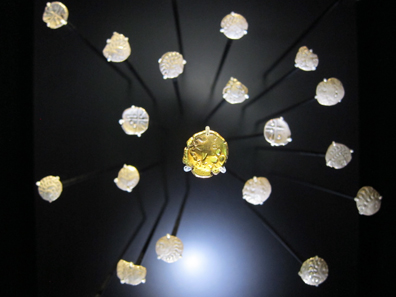

Rainbow cup of ATVLLOS surrounded by kreuzdinarii and büschelquinarii, c. 100 B. C. Photograph: KW.

The highlight is a rainbow cup stating the name “ATVLLOS”. It is very tempting to identify him as a local mint master.

Reconstruction of a Celtic mint. Photograph: KW.

A drawing provides information about how these coins were manufactured. Please don’t focus so much on the man in the blue garment striking coins in the foreground – most probably, most coin aficionados are familiar with that procedure anyway – but on the man wearing the green trousers standing near the pair of scales. He measures out gold pellets to be filled into the so-called tüpfelplatten which were used to get coin planchets. Hence, the man in the brown outer garment holds such a tüpfelplatte above a fire to smelt the granules and make them turn into a planchet.

Tüpfelplatte, found in Gerlingen, Ludwigsburg district, 2nd/1st cent. Photograph: KW.

These tüpfelplatten have been discovered in virtual every larger Celtic settlement.

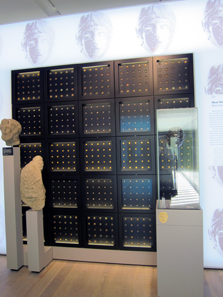

Roman coins. Photograph: KW.

The exhibition’s presentation of the Roman coins needs some getting used to. Apparently, the architect pushed his concept through – and the enthusiasm of the architect for the beauty of the small things was likewise small, as it is clearly evident.

Interactive feature on numismatics. Photograph: KW.

This little feature, in contrast, is successful. The goal is to assemble the coins in the right way to learn more about what had happened under a certain Roman emperor in Wuerttemberg.

Domitian and Domitia. Photograph: KW.

Only insiders will notice that Domitian is shown below his wife Domitia here.

Treasure trove of Köngen, Esslingen district, 3rd cent. A. D. Photograph: KW.

Any number of treasure troves have been found in Wuerttemberg, like the Köngen hoard consisting of 615 antoninians and denarii with the youngest piece dating to the era of Philippus Arabs (244-249).

Alamannic phalerae disc of a horse’s harness. The visual decoration shows a rider flooring an enemy. Grave find from Pliezhausen, early 7th cent. Photograph: KW.

While barter economy had come into use again already under Diocletian, money almost entirely vanished from Wuerttemberg during the Migration Period. Then rich people stood out with other items again, such as precious jewellery.

Judas’ purse right in the middel of theTtaking of Christ. Suffering of Christ relief from Zwiefalten Abbey, around 1520. Photograph: KW.

Although, admittedly, many coins were circulating during the Middle Ages and the Modern Times, these are not the main focus of the exhibition. On the other hand, the visitor comes across numerous objects with numismatic overtones. The relief depicting the Suffering of Christ from Zwiefalten, for example, illustrates the dislike a pious Christian had for money and its potential to allure.

The bishop of Constance in the council of Eberhard the Clement. 1575-1583. Photograph: KW.

It is much more exciting to watch the bishop of Constance taking his wallet off his garment. This scene can be seen on a painting commissioned by Louis of Wuerttemberg (1568-1593) who was proud of his ancestor Eberhard the Clement (1392-1417) because he successfully attracted such influential figures like the bishops of Augsburg and Constance to his court.

Dr. Matthias Ohm shows us the highlights of his collection. Photograph: UK.

By the way, Dr. Matthias Ohm took the time to give us a tour through the exhibition. He is in charge for the Coin Cabinet, militaria, weapons and regional studies.

John Frederick, Duke of Wuerttemberg, neujahrsmedaillen, 1627 (reverses). Photograph: Hendrik Zietasch.

Mr. Ohm shows us two medals here, whose reverses depict the old site of Freudenstadt, destroyed by fire in 1632.

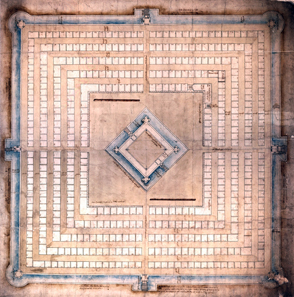

Drawing on the expansion of Freudenstadt. Hauptstaatsarchiv Stuttgart N220 B 14, 1 Bl. / Wikipedia.

As late as 1604, it had been planned to enlarge the city. The castle, projected here, in the center of the vast square was never realized.

Wooden model for a portrait medal of Christoph of Wuerttemberg by Christoph Weiditz. Augsburg, 1533/4. Photograph: KW.

One telling example of the magnificent works of the minor arts created on behalf of the Wuerttemberg dukes is the wooden model for a portrait medal of Christoph of Wuerttemberg.

Content of the foundation block for a new grammar school whose construction had begun in 1685. Photograph: KW.

With that, the exhibition gently takes us into Modern Times. Numismatic objects are interspersed here as well, like the content of a foundation stone laid in 1685 when a new grammar school was built in Stuttgart. Walled in were an inscription tablet made of tin, two bottles containing red wine and white wine, and …

Gold medal on the occasion of the first stone laying of the new grammar school of Stuttgart on 27 March 1685 conducted by Duke Frederick Charles. Photograph: KW.

… two gold and silver medals each depicting the school projected.

Caricature medal on the execution of ‘Jud Süß’ (1698-1738), 1738. Photograph: KW.

The famous “Jud Süß” mustn’t be omitted here or, to be precise, Joseph Ben Issachar Süßkind Oppenheimer, who served Charles Alexander Duke of Württemberg as financial advisor. On his order, Oppenheimer tried to match the country’s desolate financial situation with the ducal need of money. That was enough already to get on the people’s bad side; given the fact that he governed Protestant citizens, himself being a Jew who acted on behalf of a ruler who had converted to a Catholic it becomes evident why Oppenheimer fell victim to public anger after the death of Charles Alexander. His show trial ended with the death sentence on 9 January 1738. He was executed a month later. His corpse remained in an iron cage in which the former financial minister was put on display.

Many people are still familiar with the fate of “Jud Süß” because literature and, to an even greater extent, films centered on this interesting figure. Wilhelm Hauff and Lion Feuchtwanger stress the injustice of the sentence just like a first Anglo-American movie with the title ‘Jew Süss’. Infamous became the interpretation of Veit Harlan, first performed in 1940 at the behest of the National-Socialist German government.

Die of the prince-provost of Ellwangen Abbey, Anton Ignaz of Fugger-Glött (1756-1787). Photograph: KW.

Let us conclude our small numismatic tour of the new permanent exhibition of the Landesmuseum Württemberg with the dies for the thaler of the second last prince-provost of Ellwangen Abbey, Anton Ignaz of Fugger-Glött, one of the more pleasant characters of absolutism. He balanced the finances of Ellwangen Abbey and did much to improve the economic situation of the people before he became Bishop of Regensburg where he likewise reformed the institutions.

A view inside the permanent exhibtition. Photograph: KW.

It is the 19th century the new permanent exhibitions ends with, a permanent exhibition that is truly worth a visit – whether you have in interest in numismatics, history, archaeology or are interested in general.

Further information on the Landesmuseum Württemberg you find here.

We reported already on the opening of the permanent exhibition.

Here you can discover some outstanding objects of the collection online. There is plenty numismatic to see.

The Landesmuseum Württemberg has its own YouTube channel – and the demonstrations of how spatha, franziska and sax worked has actually turned out so well that you have to look for yourself, under all circumstances.

FYI, when the temperature in August 2013 rises above the 25 degrees Celsius mark, the museum charges no entrance fees!