by Ursula Kampmann

July 11, 2013 – The mood was subdued as we sat in our hotel after returning from the Toyota repair shop. They had said it was probably the injectors. They weren’t available in Turkey for this engine type, but could be flown in from Germany. The ADAC (German Automobile Association) would organize everything.

Friday May 3, 2013

We sat in the hotel, staring fixedly at our cell phone and waiting for (hopefully good) news from the ADAC operations centre. It wasn’t until around noon that the phone rang – as already said, they couldn’t get their hands on the replacement parts in Turkey, but they could be ordered from Germany. ADAC would have them flown to Turkey at their expense, and we would just have to pay for the parts themselves. Still, that came to around 3,000 Euro. Furthermore, as an ADAC member and owner of the car, I was the only one who could pick up the parts from the airport in Izmir. It would take at least three working days for the parts to arrive, and as it was already Friday afternoon, we were looking at next Thursday, at earliest. Of course there was also the chance that even then, the problem wouldn’t be fixed. At any rate, we’d have to factor in another two days as well, just for the repairs.

When we got the call we were sitting in a crummy bar with even crummier food. Pamukkale isn’t exactly a hub for high-end tourism. Sitting at the next table was a bunch of very loud, very shrill and not so young tourists, their bodies spilling out of their bikinis. I looked around and asked myself, did I really want to spend almost 10 days of my holiday here? ‘Umm,’ I timidly asked the man from ADAC, ‘Is there another option? Can you get the unrepaired car back to Germany?’

Yes, in fact, they could. This, I learned, is why ADAC offers a return service, a privilege I could make full use of since I possessed the foreign writ of protection. The only problem would be having the stamp for my car officially removed from my passport, as I would not be allowed to leave with this stamp, but without the car. I could have this done in Izmir or Istanbul. They recommended it be done in Izmir, not just because it was closer, but because customs there was also less convoluted. Sage advice, but more on that in the next chapter …

As long as we were in agreement, ADAC would deal with it and let us know over the course of the day when the car could be transferred. We would have to organize our own trip though, which wasn’t a problem – every Turkish tourist town has private travel agencies offering all sorts of services. Given our vast amount of luggage (it’s only in these kinds of situations that you truly realize just how much you can pack into a small car), we decided to take a private taxi instead of the public bus. We booked a taxi and hotel in Izmir, and then spent the rest of the day trying to sort out what could stay in Turkey and what absolutely had to go home with us.

In the evening we got the call: Our car would be in Izmir on Monday, but they couldn’t say yet how long the customs clearance would take.

The ascent to Hieropolis – even late in the day, it’s teeming with activity. Photo: KW.

Saturday May 4, 2013

We still had one more day in Pamukkale, and we wanted to use it to have a good look at the excavation and the limestone terraces. After all, this place in the ‘middle of nowhere’ does have a UNESCO World Heritage site that draws millions of tourists a year to Hieropolis. And although Turkey has recently stripped the Italians of their excavation rights so that they might do it faster themselves, the excavation itself isn’t really that important. It’s the warm water in the small white baths that really draws the crowds.

On the way to the top. Photo: KW.

We had no other choice now – instead of taking the easy route through the mountains, we’d have to buy our tickets and hike in the blazing sun up the awkward, slippery limestone to the top. This is why we’d decided yesterday afternoon to set out early the next morning, when it wouldn’t be so hot. We had been dreading the climb. But in retrospect: This is truly a once-in-a-lifetime experience that no one should miss. We had the opportunity to explore the wonderful formations in complete peace and quiet in the gorgeous morning light.

The limestone formations at their best. Photo: UK.

First and foremost, the limestone isn’t slippery at all. Quite the opposite, in fact. Even though you might have a tendency to tread carefully at first, the ground has a rough surface that makes walking easy. At no point do you feel unsafe, even in the flooded areas. We barely got the chance to give a thought to our safety anyway, since we were too busy laughing at the playful wild dogs that barked loudly as they joined every tourist on their ascent.

Bathing fun. Photo: KW.

It was only when we got to the upper area of the limestone terraces that it filled up with people, and I mean really full. The bathing bikini beauties came from all over the world, and bathed alongside modest Turkish women who didn’t remove a strip of clothing as they waded in the water. The main focus again, though, was seeking out the perfect photo opportunity – and so at any given time, there would be one woman or another trying to leave the enclosed area to find a quiet little spot amidst all the hubbub where it would look like they had Pamukkale all to themselves.

Bathing fun. Photo: KW.

We sat at the edge and took in the absurd goings-on. Every time someone tried to leave the bounded area, a Turkish guard dashed forward and blew their whistle loudly. The simple fact is this: The limestone terraces where rebuilt only a few years ago, at significant cost, effort, and scientific assistance. Before that, mass tourism had rendered them unsightly and gray, as so many people had left their mark there and the hotels above the ruins had siphoned off the calcareous water over the ruins such that the traces could no longer be removed. Today there are no more hotels above the terraces and the water is conveyed via an ingenious system, whereby it alternates over the different areas of the region such that everything looks appetizing and beautifully white.

Quiet enjoyment. Photo: KW.

It seems that the tour guide had failed to inform their guests about any of this, though, since one woman who had sat down next to us suddenly asked: ‘why is he whistling all the time?’ We explained it to her and started up a conversation. She was from Athens and was extremely impressed at how fast and effectively the Turks had developed their infrastructure. The old hereditary enmity between the Turks and the Greeks seems to have vanished in recent years. And now, the Greeks have discovered Turkey as a close and affordable holiday destination.

The woman told us that she wouldn’t be that interested in the ruins anyway, that they were the same everywhere. By now, she’d developed a theatre phobia as well (Kurt nodded sympathetically). But she felt these white terraces were something special. We had a slightly different take on things, and decided to have a proper look at Hieropolis.

Hieropolis. Bronze, 2nd century AD. Rev. Hades ravages Persephone. Gorny & Mosch 160 (2007), 1932.

Hieropolis is not quite as old as other cities in Asia Minor. Or, rather, let’s put it this way: the archaeological remains cannot be dated quite as far back. The founding of the city may only have taken place in the 3rd century BC under the Seleucids, or perhaps even later, under Eumenes II, around 190 BC. In any case, at that time, the famed ritual sanctuary, the plutonium, the entrance to Pluto’s Realm, was already in existence. Its poisonous gases were described by many ancient writers. And it was only the Galli, the castrati of Cybele, who dared enter the sanctuary in order to have the questions of the paying faithful answered by the oracle of Plutonium.

Hades ravages Persephone – this time from the theatre frieze of the city. Photo: KW.

Hades was a god not particularly well suited as a main focus for the central cult of an emerging Hellenistic city. This is why Apollo Archegetes was established.

Province of Asia. Hadrian, 117-138. Cistophor. Rev. Apollo Archegetes with cithara. Gorny & Mosch 204 (2012), 1803.

That this Apollo with the cithara is not a Musagetes or even a Kitharoedos, as archaeologists are wont to say, is evident from the dedicatory inscription of the theatre: ‘To the Apollo Archegetes and the paternal gods …’

Apollo Archegetes – again from the theatre frieze of the city. Photo: KW.

In fact, the Apollo myth is depicted in full detail on the frieze of the theatre. There’s the tournament with Marsyas …

The flaying of Marsyas. Photo: KW.

… wonderfully presented in plastic with Athena as arbiter and the final flaying. Also depicted is the birth of the twins Artemis and Apollo, as well as the legend of Niobe and her 14 children, of whom she bragged arrogantly to Leto.

The death of Niobe’s daughters. Photo: KW.

Naturally, this kind of human arrogance could not go unpunished by the gods. Apollo and Artemis killed all Niobe’s sons and daughters with their arrows.

Hieropolis. Caracalla, 197-217. Rev. Cybele between two lions, sitting facing right. Münzen und Medaillen 16 (2005), 517.

But let’s get back to the history of Hieropolis. In 188, the city came under the control of the Attalids and in 133, the Romans, under whom the city experienced its heyday. That’s because the warm waters aren’t just a tourist attraction, but can also be used for more effective dyeing. Dyer’s madder ( ‘rubia’ in Latin) was extracted at Hieropolis that produced a not as intense, but far cheaper red tone than the prohibitively expensive purple.

Tomb of Flavius Zeuxis. Photo: KW.

Red wool fabrics made the dyers’ guild of Hieropolis rich – so rich, in fact, that they could afford, at their own expense, to decorate the first and second levels of the theatre with marble from Dokimeion, about 250 kilometres way. And it wasn’t just the dyers who were doing good business – we know from Flavius Zeuxis, the owner of an ornate sepulchral structure in the northern necropolis, that he became rich through the trading of goods procured in Hieropolis, namely those famous woollen fabrics.

Hieropolis. Nero, 54-68. Rev. Horseman deity facing right. Gorny & Mosch 134 (2004), 1994.

Under Nero, an earthquake destroyed the city. It was rebuilt even more magnificently. There were setbacks, of course, like the Great Plague under Marcus Aurelius. At that time, the city fathers of Hieropolis sought advice from the Oracle of the Apollo of Claros. Apparently they didn’t trust their own god Hades in such matters. Perhaps it was believed that it was in the interest of the Lord of the Underworld not to bring a premature end to the plague …

The same horseman deity with double axe on a funeral monument. Photo: KW.

The city experienced its greatest prosperity under Septimius Severus. The sophist was responsible for the connection to the imperial house. He became tutor to Caracalla and Geta and also oversaw the imperial house’s correspondence with the Greek cities.

The coronation of Septimius Severus in the theatre frieze. Photo: KW.

Many of the city’s most beautiful buildings date back to this period. Even the magnificent theatre frieze, some of whose reliefs we have already shown, came about under Septimius Severus. The influence of the Hieropolitan Antipater waned, however, with the murder of Geta. He had likely been involved in the conspiracy against Caracalla. In any case, Elagabal conferred the title of Neocoria upon Hieropolis, as an important sanctuary of Cybele, and the city managed to emerge relatively unscathed from the period of the soldier emperors.

Sign pointing towards the tomb of Philip. Photo: KW.

The metropolis of Phrygia flourished in the 5th and 6th centuries as well, and became an important centre of early Christianity. The apocryphal acts of Philip tell of a Viper cult that was abolished through the intervention of the holy Philip the Deacon. Sadly, we didn’t get to visit the tomb of Philip since, unbelievably, it started to rain cats and dogs as we were on our way there. Anyhow, even the knights of Frederick Barbarossa knew the score when it came to St. Philip, as the following is written about the city in a contemporaneous chronicle, ‘…, that the Apostle Philip is buried in it.’ Back then, there were just a few farmers settled here, as an earthquake had destroyed the city in the second half of the 7th century. Although another Byzantine castle was erected, the city’s heyday had come to an end. Hieropolis was now nothing more than a quarry for the Saljuqs.

Theater of Hieropolis. Photo: KW.

The city area is really too large to see everything properly – at least not without losing interest. Most importantly, you have to be fairly light on your feet (and also willing to make use of this skill), an attribute that only really applies to a tiny fraction of visitors. So that everyone doesn’t just cluster around the few square metres of hot baths the entire time, the Pamukkale city administration has organized buses to take people around the grounds for free once they’ve paid their admission ticket. Even so, there weren’t that many people that could be lured away from the hot baths …

Museum of Hierapolis. Photo: KW.

Sitting in the centre of the excavation are the large thermae that were built in the 2nd century AD. Today, they house the archaeological museum, which not only has the finds of Hieropolis, but also those of neighbouring Laodiceia ad Mare, …

Sarcophagus from the necropolis of Laodiceia ad Mare. Photo: KW.

… which was also the place of origin of magnificent sarcophagi.

Relief with depiction of a bullfight. Photo: KW.

Also of particular appeal to the numismatist are various reliefs of the 3rd century AD …

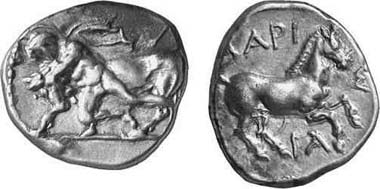

Larisa. Drachm, 440-400. Obv. bullfighter, coat flapping, subdues the bull by grabbing it by the horns. Gorny & Mosch 117 (2002), 197.

… with bullfights, which immediately make one think of the coins from Larisa in Thessaly.

Coins on display. Photo: KW.

There are, of course, also a couple of display cases featuring find coins from Hieropolis.

A view of the museum depot under open sky. Photo: KW.

Even more interesting is a look at the museum’s open-air depot that reveals which great treasures are still waiting to be published and discovered.

Wasp nest on one of the capitals of the stoics bordering the agora. Photo: KW.

As is our tendency, we were fascinated by completely unrelated things – like this small wasp nest in the making on an impressive column capital.

Northern Necropolis. Photo: KW.

The most impressive part of the excavation is probably the northern necropolis. Maybe it’s because there are fewer tourists there than in the rest of the excavation, and perhaps because the terrain there seems more authentic, less geared towards tourism.

Wedding photo in front of ruins. Photo: KW.

Incidentally, many Turkish couples from the surrounding area choose the ruins of Hierapolis in evening light as the backdrop for their romantic wedding photos.

View at sunset of the limestone terraces. Photo: KW.

And you can understand why. Rarely have I see anything as picturesque as the limestone terraces of Hieropolis at sunset (and without bathing tourists).

And with that, we’re just about ready to make our way back home. Join us on the last leg of our journey as we visit Smyrna. There, we learn not only how Turkish customs and traditions operate with respect to Byzantine bureaucracy, but also visit the most shoddily and carelessly assembled museum we could find in Turkey.

You can find all parts of the series ‘Springtime in Turkey’ here.