by Ursula Kampmann

June 20, 2013 – There’s a classic excursion that everyone who has stayed in Kusadasi does – it ticks off the three most attractive nearby ruins: Priene, Miletus and Didyma. We didn’t want to take the classic tourist approach, however, and decided instead to split up the day, with one excursion to Miletus and Didyma, and the second to Priene.

Monday April 29, 2013

When I first visited Didyma in 1983, there was a temple and not much else. Today, it’s considerably more touristy. There are large parking lots about 500 metres from the ruins, and from there, a modern processional way leads to the excavation, which is lined with souvenir shops. Most of them were still closed when we got there at around 10:00 am. We were too early. After all, it’s not for nothing that the organizers bill the day as ‘Priene, Miletus, Didyma,’ where Priene is the first stop, then Miletus, and Didyma last. So peak activity around here tends to be in the afternoon.

Miletus. Bronze, around 200 BC. Obv. Statue of Apollo of Didyma. Künker 133 (2007), 7586.

It’s said that an Asia Minor mother goddess identified by the Greeks as ‘Leto’ was originally worshipped in the sanctuary of Didyma. In Didyma (from the Greek ‘didymoi’ = ‘twins’), Leto gave birth to – at least according to the firm belief of the residents of Miletus – Apollo and Artemis. And from there, it was really just a small step to the oracle of Apollo. The Temple of Apollo at Didyma became one of the most important sanctuaries in archaic Asia Minor. Herodotus tells us that both Croesus and the Egyptian Pharaoh Necho sent votive offerings to the Branchidae, as the local priestly caste was known. The wealthy city of Miletus was proud of their cult, of course. So proud, in fact, that a rival structure to the neighbouring Artemision in Ephesus was planned.

It’s too bad then, that Miletus then took such a prominent stance during the Ionian Revolt. The city was destroyed, as was, of course, the temple. The famed bronze statue of Apollo Didymeios with the deer on the outstretched hand, which had been created by the well-known sculptor Kanachos of Sicyon and is frequently featured on the coins of Miletus, was transported by the victorious Persians to their homeland, along with the Branchidae. It was only Seleucus I (312-281) who saw to it that both were returned.

Province of Asia. Hadrian, 117-138. Cistophorus. Rev. Statue of Apollo of Didyma. RIC 483. Gorny & Mosch 181 (2009), 1744.

By this point, the enormous new construction of the temple was in full swing. The resurrected construction tends to be associated with Alexander – and the gigantism that was at play here would seem to attest to this assumption. The giant temple was supposed to have been surrounded by 122 oversized columns. We know how much money was paid for such a column – 40,000 drachmas for labour costs alone, which corresponded to payment for approximately 26,000 days of work. When recalculated in light of present-day hourly craftsmen rates, it’s clear that Miletus miscalculated. This effort and expenditure could plainly not be reconciled with the city’s economic power, even with the occasional reasonable grant from an emperor. The temple was still an unfinished site when, 600 years after its construction began, paganism was abolished.

Front view of the Temple of Didyma. Photo: KW.

Still, I have to admit – Didyma is the most impressive unfinished ruins I’ve seen in my life. The complex measures about 50 metres by 110 metres. The columns were almost 20 metres high, which alone is overwhelming!

Nothing but dirt. Photo: UK.

Have a laugh at my expense now, as I tell you about how, despite the imposing temple, I still managed to be completed distracted by a small swamp …

On closer inspection … a lot of frogs. Photo: UK.

On closer inspection, there were all sorts of frogs that leapt away en masse when you got too close to the swamp. I’ll admit, I went past the swamp several times, just because I took such great delight in all the jumping and splashing!

A Greek tortoise, living in Turkey. Photo: KW.

Then, a rather large Greek tortoise crossed our path. Have you ever actually watched just how fast these creatures move, despite the fact that they look fairly ponderous at first? Again, I have to admit; we spent a good half hour busying ourselves with Didyma’s local fauna before finally getting to the actual architecture.

The way up to the large Temple gate. Photo: KW.

We climbed up to the atrium. In ancient times, three gates led to the temple interior, which was likely just as rarely used then as now.

Covered entrance. Photo: KW.

Instead, we went through one of the three narrow, covered passageways, …

Adyton. The inner courtyard of the Temple, open at the top. Photo: KW.

… into the so-called adyton. This courtyard was originally surrounded by an approximately 20 metre high wall, five metres of which still stand and are more than impressive enough on their own. The interior is where the cult images of the God may once have been housed, as is also the case, incidentally, in the Apollo Temple at Delphi. This also most certainly included a laurel tree and a spring, above which a small shrine was erected, traces of which can still be seen today. Some archaeologists would view this shrine as architectonic framing of the bronze statue of Kanachos, but it’s more likely that this is where the process of the oracle finding happened, in order to conceal it from profane eyes. After all, the immediate area had everything one needed for an oracle: Holy Water, Mother Earth – the bedrock extended right up to close to the spring – and also likely the laurel tree. Perhaps there was also a cult statue in the vicinity, but it certainly wasn’t the bronze votive offering, but rather a shapeless wooden stake, similar to the cult statue of Athena in Athens, which has absolutely nothing to do with the statue of Phidias.

Definitely not an architectural blueprint. Photo: KW.

Of course, we also looked for the famous architectural blueprints of Didyma. If I recall correctly, I had also looked for them back in 1987 when we took a trip through Turkey from the university and I had to give the lecture about Didyma. Today, as back then, I failed to find the up to 25 metre long lines and arcs measuring 4.5 metres in diameter. It’s no wonder that these drawings were only discovered in 1979! Even when you look for them, you can’t find anything. And I have yet to see a single good image of these blueprints that would make it possible to find the original.

Museum of Miletus. Photo: KW.

We didn’t take the sacred road from Didyma to Miletus, even though it’s been well excavated and reconstructed in recent decades. We used the normal road, which meant that on our way, we passed the newly established museum in which the discoveries from Miletus, its surrounding area and Didyma are on display.

Ceramics with linear A-script in the Museum of Miletus. Photo: KW.

If we believe the words of Ephorus of Cyme, a historian from the 4th century BC, Miletus is said to have been founded by the Cretan Sarpedon, youngest son of Zeus and Europa, and brother to Minos and the judge of the dead Rhadamanthys. In fact, one of the earliest exhibits in the museum is the fragment of a vessel that contains linear A-script.

Map of Miletus. Photo: KW.

In those days, the landscape was completely different to its current layout. Where today, you park your car in the middle of a flood plain, there was nothing but sea 3,000 years ago. Miletus lay on a spur of land on which archaeologists have found almost as many Bronze Age strata as in Troy. Around 1100, the city was then destroyed so that Ionic colonists – according to legend – could found the city anew in the year 1053 BC. The myth says that a son of the last King of Athens led the settlers there, which led to attempts to explain the close alliance between the two cities.

Miletus. Stater. Gorny & Mosch 190 (2010), 261.

The city experienced its heyday during the archaic period. She sent her sons into the world to found about 80 (sic!) colonies. The rich granary on the Black Sea Coast, in particular, was developed by Miletus. Sinope, Amisus, Trebizond, Feodosia, Kerch, Abydus, Cyzicus and Proconnesus all came about due to the involvement of Miletus. There were even Miletian merchants living in Naucratis, the famous Greek colony in Egypt.

Miletus was so wealthy and powerful at the time that it won a war under the Tyrant Thrasybulos against the neighbouring Lydians and, as such, remained autonomous, while most other Ionian cities had to submit themselves, under Croesus at latest.

Miletus 1/12 stater. Gorny & Mosch 200 (2011), 1818.

Miletus is also famous for its spiritual life – Thales calculated a solar eclipse for the year 585, Anaximenes and Anaximander did research into the primordial matter of the world, and Hecataeus authored a fundamental travelogue of the then-known world, which Herodotus enjoyed quoting extensively.

The Island of Lade – today, just two small hills in a flood plain. Photo: KW.

It was only when the Persians conquered the Lydian empire that Miletus also came under foreign rule. A pro-Persian tyrant was appointed who, if we are to believe Herodotus, is to have been to blame for the Ionian Revolt. More specifically, he had persuaded the satraps in charge to start a war against Naxos. This was pretty much a complete flop. So as not to have to explain themselves before the Great King, the two are said to have initiated an Ionic independence movement.

Although the Ionian Revolt did perhaps come about due to personal motives, it’s quite certain that there were also economic factors at play: The Persian invasion of Egypt put an end to trade via Naucratis, and following the Scythian campaign in 513/12, merchant ships were also absent from the Black Sea. So perhaps it was less a matter of liberation from the yoke of the Persians than it was a matter of defending their own prosperity.

We don’t have to repeat the entire story of the Ionian Revolt here. Only Athens and Eretria had sent a few ships as reinforcement. The Ionians alone were no match for the roughly 600 ship strong Persian fleet. A battle took place at the Island of Lade, off the coast of Miletus, and the Greeks lost. The revolt failed. Miletus was destroyed, and Athens had provided a good cause for the Persian Wars of the next decades.

Miletus. Drachm of the Alexander-type, 295-275. Gorny & Mosch 190 (2010), 173.

Miletus was rebuilt, of course. And it joined the Delian League. It remained allied with Athens until 412, when the arrogant rule of the Athenians led to Miletus being on the Spartan side during the Peloponnesian War. With the Antalcidas Peace, at latest, Miletus was back fully under Persian control. And when Alexander the Great took over the former Persian Empire, Miletus was at the mercy of changing fates during the Diadochi Wars.

Miletus. Tetradrachm, 352-325. Gorny & Mosch 211 (2013), 362.

Miletus belonged, at some point or another, to each of the various empires that fought over Asia Minor. And even when the Romans assumed the heirship of the Attalids in 133, peace did not return. Peace would only come when Augustus became sole ruler. He instigated a late boom for the city, but Miletus could not keep up with the provincial capital of Ephesus and the up-and-coming port of Smyrna. Miletus remained – even in Byzantine and Turkish times – a local centre that only disappeared in 1400, when the harbour silted up once and for all.

Statue of the Meander river god. Photo: KW.

The museum of Miletus is truly worth a visit. It provides an excellent overview on the history of the city. Of particular note was a statue of the Meander river god …

Relief of the Apollo Delphinios.

… and a relief of the Apollo Delphinios. Miletus’ most important sanctuary was devoted to him. The ceremonial procession regularly moved along the sacred way from Apollo Delphinios to the Apollo at Didyma. Delphinios comes from Delphi – and, in fact, this relief of Apollo depicts him as we know him from his most important Greek sanctuary: with a bow, an omphalos at his feet around which the snake is coiled and, to his left, tripod and laurel tree. If you’re interested in a little detour to Delphi, click here.

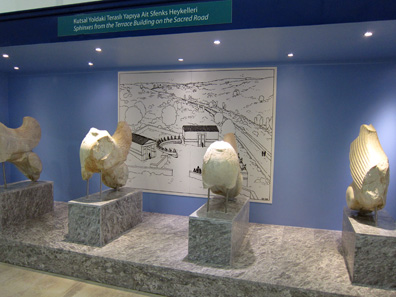

Sphinges from the sacred road. Photo: KW.

Finds from the sacred way are also on display in the new museum …

Display case with coin finds in the new Museum of Miletus. Photo: KW.

… as are coins, of course.

Hoard discovery of Söke Tekkisla. Photo: KW.

Among them is the hoard discovery of Söke Tekkisla, which came to the Museum of Miletus in 1996. It consists of 125 Ottoman gold coins, minted almost exclusively under Suleiman I, and 174 contemporaneous Venetian coins. There are also 676 Ottoman silver coins. According to the plaque, ‘the Tekkisla hoard is of special importance as to reflect the economic state of the Period as well as its political and military aspects.’ While I understood the economic conditions reference, I wondered what political and military aspects I was supposed to be taking away from it. It was probably just another case of me being somewhat naive by taking a plaque label seriously.

Lion on a skewer. Photo: KW.

The small collection of reliefs and inscriptions found in the museum’s garden were also very nice. And I couldn’t possibly miss this opportunity to show you my absolute favourite object: a lion on a skewer.

The theatre of Miletus. Photo: KW.

We arrived at Miletus during the hottest part of the day. The sun beat down mercilessly.

Spectator entrance to the theatre. Photo: KW.

Through one of the wonderfully preserved spectator entrances, we managed to make it to the top level of the theatre where you get a spectacular vista. I sat there sweating, and philosophized about whether the few remaining preserved ruins could be worth running around the countryside in the midday heat.

A look at the Faustina thermae. Photo: KW.

They weren’t. I took a quick look at the Faustina thermae, and wasn’t even tempted to move in any closer.

Small snake in the bath. Photo: KW.

We watched a small, harmless snake taking an invigorating dip …

Caravanserei from the 15th century. Photo: KW.

… and then decided to have a look at the caravanserei from the 15th century, which houses – quite sensibly – a small cafe. Here, at the coolest spot in Miletus, we recuperated a bit.

A wide range of fake coins on offer. Photo: KW.

We were soon restored again and ready to take in the wide array of fake coins available for purchase.

A view of the small Meander River. Photo: KW.

We drove back across the big Meander River – in Turkish ‘the Büyük Menderes River’ – to touristy Kusadasi and were delighted to get to the calm of our luxury hotel’s garden.

Join us next week as we visit Priene, famous for its well-preserved city remains.

All parts of the series ‘Springtime in Turkey’ can be found here.