by Ursula Kampmann

May 23, 2013 – There’s an old Sicilian proverb that says, ‘Only donkeys and tourists go out in the midday sun.’ But for us, lunchtime afforded us the glorious opportunity to take in Pergamum all on our own.

Thursday, April 25, 2013

I have a very particular, personal relationship to Pergamum. After all, I wrote my dissertation on Imperial Era Pergamum, on its Homonoia alliances, to be exact. Anyway, I completed my doctorate while already working full time, and it was a nightmare trying to do both at once. And so, as a result, I have an ambivalent relationship to Pergamum – on the one hand, I hold it near and dear to my heart because of all I learned about its history, but on the other hand, I had gotten so fed up with the word ‘Pergamum’ at times that I couldn’t even bear to hear it anymore. It would have been worth considering at least driving past Pergamum, but we never managed it at the time. And for this, Athena rewarded us …

Little Owl, waiting for us in broad daylight at the entrance of Pergamum. Photo: KW.

She even sent us a small welcome: A Little Owl sat at the entrance, waiting for us in the middle of the day. The Goddess of Wisdom couldn’t have been all that dissatisfied with my dissertation after all.

Cable car up to the acropolis of Pergamum. Photo: KW.

But let’s start at the beginning. We were actually somewhat surprised that it is now forbidden to drive up to the acropolis of Pergamum. Instead, there’s now a cable car whose gondolas fill up with the five-figure number of tourists that spill out of the thousands of tour buses daily in summer.

View of the city from Ascleipion. Photo: KW.

Since we had set out a bit late that morning, without any particular rush to reach our destination, we didn’t have to wait and had a gondola all to ourselves.

Pergamum. Commodus, 180-192. Medallion. Rev. Heracles sitting facing left, his hand reaching out to Auge. Gorny & Mosch 196 (2011), 3202. It’s not clear whether this is a contemporary stamping or a modern-era imitation.

As with any good Greek city, Pergamum has a myth surrounding its founding: The king of Tegea had received an oracle in Delphi revealing that his grandson was going to kill his (the king’s) sons. In order to prevent this, he took measures and made his daughter Auge a virginal priestess in the Temple of Athena, where Heracles did more than just admire her from afar. In fact, Auge bore him a son that she named Telephus. Obviously, her father was none too pleased by this development, and the daughter was to be cast out to sea on a boat to drown …

Damascus (Syria). Philip the Arab, 244-249. Bronze. Rev. Telephus is suckled by a doe. Coins and Medals 20 (2006), 621.

… the son was brought to the mountains, where he was suckled not by a female wolf, but by a doe. As an adult, he found his mother again living with the childless King Teuthras in Mysia. The son would almost even have become the mother’s husband, but a snake prevented this by crawling into the bed between the two. Mother and son recognized one another, Telephus found his place in the court – and found himself embroiled in the Trojan War, as the Greeks had taken a wrong turn on the route to the actual war destination and found themselves in Mysia. They battled against the Teuthrians and were defeated by Telephus (who did as the oracle had said), but he suffered a wound from the spear of Achilles during it. There was another oracle that said, firstly, that Telephus could only be healed by the person who had inflicted the wound, and that Telephus was predestined to lead the way to Troy. Telephus then kidnapped Orestes and forced his father, Agamemnon, to force Achilles to heal him. This was only achieved when Odysseus came up with the clever idea that if Achilles wasn’t able to heal the wound, then likely some rust scraped from his spear would (what this says exactly about the condition of the weapons of the heroes at Troy has, as far as I know, not yet been scientifically investigated). The wound was healed. Telephus led the Greeks to Troy, but didn’t want to take part in their war, as his wife was a sister of King Priam. He returned home and founded Pergamum; which brings us back on topic …

Pergamum. Gongylos(?). Diobol, around 420. Rev. Satraps head with tiara facing right. Gorny & Mosch 207 (2012), 278.

For us, Pergamum first becomes historically tangible in Xenophon’s Anabasis. In the year 399, his tens of thousands were warmly received there by the widow of Gongylos.

Pergamum. Heracles, son of Alexander the Great, + 309(?). Gold stater, prior to 309. Lanz 149 (2010), 172.

The heavily fortified Pergamum became significant during the Hellenistic Period. By right as victor, Alexander had raped the Persian Barsine (despite historians often rewriting this more coyly as ‘made her his mistress’). The result was a son that Alexander – modest as always – named Heracles. He was brought to Pergamum. Of course, when Alexander died without rightful heirs, this son took on great importance. Polyperchon used the 18-year-old to aid him in threatening the authority of Cassander, who had just murdered Alexander IV, son of Roxane. Cassander relented, relinquished rule of Peloponnesos to Polyperchon, and as a symbol of the newfound peace, Heracles and Barsine were murdered.

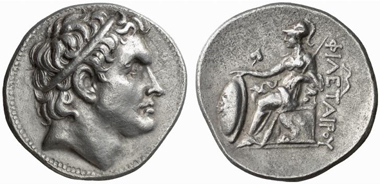

Seleucus I. Tetradrachm around 280, Pergamum. Gorny & Mosch 204 (2012), 1584.

In the Wars of the Diadochi, Lysimachus gained power and influence in Mysia. Pergamum was a key support. Lysimachus entrusted it to a former supporter of Antigonus, Philetaerus from Tieium on the Black Sea coast. He was likely appointed to his office after 301. One of his tasks was to guard the plundered goods that Lysimachus had amassed. There were 9,000 talents of silver stored in Pergamum. The loyal Philetaerus watched over this hoard for almost twenty years until 282, when he revolted due to the court intrigues of Lysimachus’ young wife, Arsinoe II (later to become wife-sister of Ptolemy II through a third marriage), and offered himself and the fortress of Pergamum, along with all its treasures, to Seleucus.

Philetaerus for Seleucus. Tetradrachm, ca. 269/8-263. Lanz 125 (2005), 342.

Lysimachus was defeated by Seleucus in 281 at the Battle of Corupedium. But Seleucus too was not to live much longer – Ptolemy Ceraunus, second husband and also half-brother of the aforementioned Arsinoe, murdered him. With his fortress and the 9,000 talents, Philetaerus managed to gain considerable autonomy and go it alone. He founded a dynasty.

Eumenes I, 263-241. Tetradrachm. Künker 216 (2012), 373.

His successors paid tribute to him by putting his portrait on their coins. Philetaerus himself did not have children, because he was a eunuch, ancient sources claim. This needn’t have been so. Nevertheless, the Attalids therefore became great because the family ties between them worked. Eumenes I was Philetaerus’ nephew. Attalus I was a great-nephew of Eumenes I. In the third generation, there were actually sons at one point: first the oldest, Eumenes II, and then the second oldest, Attalus II.

Dead giant. Part of the so-called small Attalid votive offering that Attalus II donated for the Athenian Acropolis. Naples. Photo: KW.

Eumenes and Attalus were masters in the fine art of cooperating with the untrusting and greedy Senate of Rome. Pergamum retained its status as friend of the Romans, which brought it a lot in terms of territory growth. Pergamum inherited the bigger, more important Hellenistic lineages as freeloaders of the Roman success.

Aristonicus as Eumenes III. Cistophor, 131/130. Lanz 117 (2003), 293.

Succeeding Attalus II was Attalus III – not his son, but once again, a nephew. In antiquity, he wasn’t granted any good press – he was said to have been otherworldly, preferring to cultivate poisonous herbs rather than devoting himself to day-to-day political affairs, and so on. In actual fact, however, this strange loner’s will was a masterstroke of reality. He had named the Romans as his heirs. They were to see to it that his kingdom fell into the hands of the successor without bloodshed.

Of course, it didn’t work out this way. A usurper by the name of Aristonicus, who adopted the name of Eumenes III, gathered support among those people who did not expect any improvement to their situation under the Romans. And it ended as might be expected: The Romans were victorious, the insurgents went down without pomp and circumstance, and the hoard of the Attalids helped to fill the Roman purses.

Pergamum. Cistophor, after 133. Gorny & Mosch 212 (2013), 1729.

The Roman province of Asia grew out of the central region of the Kingdom of Pergamum, and was one of the richest regions ever to be heavily taxed by Rome. The administrative centre was relocated. Pergamum lost its preferred status as capital city to Ephesus, which was more convenient for the Romans in terms of transport connections. These were hard times for Pergamum, and time and again the greediness of the governor had to be appeased or a civil war hard to be financed. It was not until the reign of Augustus that a pleasant change was brought about.

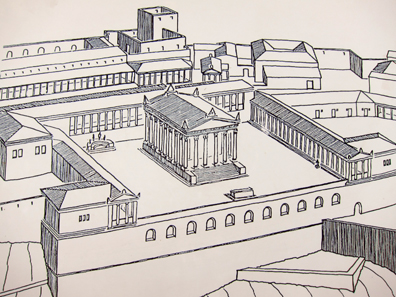

Pergamum. Claudius. Cistophor. Rev. Neocoria Temple of Augustus. Künker 226 (2013), 747.

Augustus made Asia a Senatorial province. A special honour was that only a former consul could serve as governor here. Moreover, he allowed the construction of a temple in his and the Goddess Roma’s honour, which was to serve as the place of assembly for the Parliament of Asia. This parliament wasn’t really of great political importance, but could still send delegations to the emperor on behalf of all the cities of Asia, which were permitted to, for example, complain about the administration of a governor. Pergamum was chosen as the site of this first imperial temple – and attained the sonorous title of Neokoros: guardian of the temple.

Pergamum. Elagabalus, 218-222. Rev. prize table with prize crowns. Gorny & Mosch 195 (2011), 332.

Around the middle of the 3rd century, about 120,000 people lived in Pergamum. And on top of that were the many visitors who came to seek healing in the neighbouring Asclepius sanctuary. Pergamum was thriving, and did so right up to the Byzantine Period. A Pergamum native even ascended the imperial throne for a short time: Philippicus Bardanes. But in 716, Pergamum fell to the Arabs. Although the city could be reclaimed, it never recovered from the pillaging. A small historical side note shows how the area was valued: In 1056, Pergamum was designated as the place of exile of a usurper, which doesn’t really speak volumes to it being a very pleasant place at the time. Around 334/5, Pergamum then ultimately fell to the Ottoman Empire, under which it descended into insignificance.

View of the former Temple of Athena. Photo: KW.

The culmination of the history of Pergamum is the Acropolis, which forms the focus of any visit. Many tour groups are content to just walk from the entrance to the Temple of Trajan for a start, and then have a quick look at the place that had once formed the Altar of Pergamum. And with that, the whole thing is taken care of (apart from the obligatory visit to a carpet factory). Well, we took a little more time, even if we by no means saw everything that has now been uncovered in Pergamum.

First, we went to the fundaments of the Temple of Athena, where the famous library once stood. There were once 200,000 scrolls stacked on its shelves. Marcus Antonius presented it as a gift to the Egyptian queen Cleopatra in the year 41/40.

The theatre of Pergamum, perfectly fitted into the hillside. Photo: KW.

From here you have a wonderful view of the theatre of the city, …

Hardun, also known as “sling-tailed agama” Photo: KW.

… that the reptiles also seem to enjoy. This approximately 40 cm long reptile is an agama (Laudakia stellio), also known as a sling-tailed agama. You’re better not to touch these creatures, since they can scratch and bite quite hard.

Fundaments of the Trajan Temple. Photo: KW.

Via the impressive fundaments of the Trajan Temple – despite the small number of tourists, it still wasn’t easy to take this shot without any people in it – we got to …

Reconstruction of the Trajan Temple. Photo: KW.

… the Trajan Temple. Under Trajan, the city received its second Neocoria, something that they were very proud of. Whereas other cities often economized and repurposed an existing temple as an imperial temple, in Pergamum they erected a new building.

Trajan Temple. Photo: KW.

Today, the temple is often used as a climbing frame. Some particularly popular photos are either a victory pose from a dizzying height, or that of the individualist, assuming a meditation pose atop a broken column. For women, the jumping with both feet in the air pose continues to enjoy widespread popularity – preferably combined with a billowing scarf over one’s head. Just standing there is for philistines! Interacting with the structure is key – every tourist becomes a top model in front of the ruins. How nice that archaeology can provide such a lovely backdrop! Otherwise, there would only be boring beach photos to show to people back at home!

The site of the famous Zeus Altar. Photo: KW.

One is thankful for the fact that nowadays, the site where the great Zeus Altar once stood is blocked off. Even so, during our entire tour, we didn’t see a single person in charge that seemed the least bit concerned about what us tourists were doing or whether or not we were observing the barriers.

The red hall. Photo: KW.

By now it was the afternoon, and the first big groups of tourists were storming the Acropolis again. We retreated, and passed on seeing the somewhat lower-lying gymnasium and the sacred Precinct of Demeter to instead pay a short visit to the (closed) red hall. This structure remains somewhat enigmatic. It gets its name from the many ‘red’ bricks that were used in its construction. Despite the fact that the structure is bigger than the famous gigantic Temple of Palmyra, it’s not mentioned in the ancient writings. Today, it’s assumed that Egyptian goddesses like Isis, Osiris and Sarapis were worshipped here. Perhaps there was also a cult of Cybele. Of particular note are the underground passageways and a tunnel through which a river flowed. This is all reminiscent of the mysteries that have been attracting throngs of people since the 2nd century AD. Some scientists can be tempted by this archaeological underworld scenario into seeing a labyrinthine complex in the tunnels, in which the faithful underwent frightening initiation rites.

First look at the Asclepieion. Photo: KW.

But at this hour, we were denied entry to the temple. The museum would have been open, but in light of the drive to Foca still ahead of us and the search for a hotel, we decided to just pay a visit to the Asclepieion.

Pergamum. Bronze, after 133. Gorny & Mosch 196 (2011), 1613.

In Roman times, it was famous the world over. It was founded in the 4th century BC by a private individual. It was Eumenes II who made it into a state cult. During the Roman Imperial Era, people would come from all over the empire to seek healing in a type of psychosomatic therapy. Aelius Aristides, one of the greatest orators of his time and a declared hypochondriac, created a memorial to the Asclepius cult, in that he published a meticulous diary entitled ‘Sacred Tales’ about his illness and its cure. His self-portrayal is so detailed, that doctors today still use his dreams to better understand the psyche of ancient people.

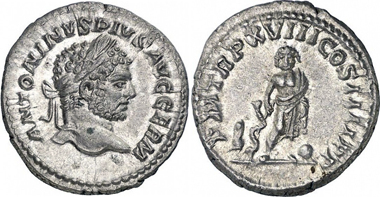

Caracalla. Denarius, 215. Rev. Asclepius of Pergamum with Telesphorus and Omphalus. Gorny & Mosch (November 2010), 475.

Emperor Caracalla also came here to try to forget the trauma that arose when, in order to prevent a civil war, he had his brother killed. The therapy was effective. This is why the Asclepius of Pergamum in its typical Pergamenian iconography found its way into Roman coinage. To the right of Asclepius is Telesphorus, a small hooded man who brought the end to of illness, for better or for worse. To his left lies a round object that is often referred to as a globe, but is more likely an omphalos.

Temple of Asclepius, built during the reign of Hadrian. Photo: KW.

There’s little left of the original temple. It was a round structure that was erected during the reign of Hadrian and looked quite similar to the Pantheon.

The holy well. Photo: KW.

As a sort of experience-it-for-yourself discovery trail, the path that former patients would have taken has been atmospherically reconstructed. It leads from the holy well …

Cryptoportico. Photo: KW.

… through an underground passage …

Burble, burble … Photo: KW.

… accompanied by the atmospheric babbling of a little brook that trickles down a flight of stairs, …

So-called “cure building.” Photo: KW.

… to the round cure building.

What’s actually been preserved from antiquity and what’s been reconstructed has been left to the visitors’ imagination.

Theatre of the Asclepieion. Photo: KW.

In front of the theatre of the Asclepieion I pondered just how far reconstruction should be allowed to go. I remember how impressed I was 20 years ago by the Turkish excavations, namely because so much was preserved and you could imagine the buildings accurately. Today, much less naive than I was then, I wondered just to what extent all these reconstructions corresponded with reality, or were built exclusively to serve the needs of tourism. How much was still available of the original Cryptoportico? To what extent does the replica of the cure building correspond to actual evidence, or does it merely reflect the ideas of the excavators? I felt like I was in a sort of archaeological Disneyland that had been built as a backdrop to fulfill my expectations.

View from the roof terrace of the boutique Hotel Erguvan. Photo: KW.

We left Pergamum and drove to Phocaea. We wanted to see where the coins with the seal were first minted. We lucked out in our hotel search and found a very decent boutique hotel just outside the city. The room was clean, the bed was good. There was a wonderful view of the coast from the roof terrace. Nonetheless, I haggled a bit on the price of the room. After all, any guidebook will tell you to do that.

Part of the wonderful breakfast at the Hotel Erguvan. Photo: KW.

In retrospect though, I was ashamed of my pettiness – because what we were served for breakfast was made with so much love and pride in their own products that the room was more than worth its price. Cheese from the region, olives and olive oil from their own grove, honey, butter and quark, as well as homemade jams. And that was only part of the breakfast! There were also eggs, small pancakes, sesame rings and much more. Every morning we were faced with the philosophical problem of whether to eat this fantastic breakfast right down to the last morsel, even though it would have been enough for the entire day. Although it was theoretically possible not to eat everything in the hopes of maybe one day managing to enjoy a lunch, we pretty much never made use of this option.

In the next chapter, we stay in Foca. We visit the ancient ruins of the ancient trading city, from which cities like the modern-day Marseille were established, and take a trip to Sardis, where at one point, possibly, the idea for the new medium of the ‘coin’ was born.

All parts of the series ‘Springtime in Turkey’ can be found here.