by Ursula Kampmann

May 16, 2013 – The European citizen takes it for granted that the government supplies him with enough small change. There may be something of a shortage thereof in exotic destinations like India – we reported on that rather frequently – but in this part of the world it seems hard to imagine getting no change at the baker’s.

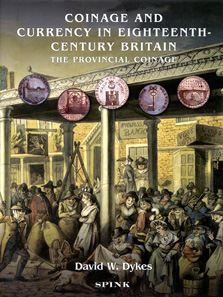

David W. Dykes, Coinage and Currency in Eighteenth-Century Britain. The Provincial Coinage. Spink, London, 2011. 383 pp. illus. throughout. Clothbound, thread stitching. 22 x 28.5 cm. ISBN 978-1-907427-16-9. £65.

We instantly recognize this as a very recent, very modern attitude when we look at the English tokens. At the end of the 18th century, Royal Mint was no longer able to meet the needs of non-face-value coins of a country that was in the process of becoming industrialized. The booming industry that paid the wages on a daily or weekly basis, and the retail trade with its demand of change coincided with the growing desire for advertisement and active collectors who bought these contemporary coins enthusiastically and hoarded them in their cabinets. Tons of private tokens were produced in only ten years, between 1787 and 1797, and not exclusively for actual use. The great number of quite well preserved specimens of this genre is no accident. Collectors’ editions came up as well as tokens for distributing political propaganda. Many a dealer sniffed a good stroke of business.

It was thanks to the incredibly detailed subjects on the tokens that collecting became such a profitable matter. They exhibit objects that are seldom encountered on official depictions. The inventory of a china shop, for example, or the machinery used by a candlemaker for manufacturing his candles, animals from a menagerie and, of course, minting presses. There is already a sufficient number of catalogs of such tokens available, but now David W. Dykes submits a bibliophilic opus with his monograph ‘Coinage and Currency in Eighteenth-Century Britain’ that illuminates the historical backdrop and introduces the manufacturers of these items.

The author presents a book which is a lot more than mere numismatics. Rather, the late 18th century society becomes alive. Already the companies’ histories of the most important token producers – Thomas William, Matthew Boulton, John Westwood, Skidmore & Son with all of their competitors – provide insight into the skills a successful entrepreneur had to possess in order to survive in an extremely competitive environment. By numerous quotations of original sources, Dyke tells their story in conjunction with information on the token issues they manufactured. The matter gets really exciting once he introduces individual commissioners and provides visual testimonies that served as model for the tokens.

Anyone able to use his imagination will enjoy this book. Auctioneers and coin dealers, menageries and glovemakers, state-of-the-art machines and stagecoaches – they all represent a new era and its people. Their way of thinking and the important role of political propaganda even back then can also be found in Dyke’s book. By means of the token it draws a pictorial broadsheet, as it were, that is a pleasure to read.

I would like to recommend this well-illustrated and carefully written book published by long-standing auction house Spink to anyone interested in the economic history of early modern times. Those who like everyday history will also enjoy this study. And it goes without saying that this opus is a must-have for every special collector of tokens.

You can find this book among the Spink publications.