by Ursula Kampmann

September 27, 2012 – This leg of our journey takes us along the old pilgrimage route towards Santiago. We visit a Mozarabic church in the middle of the mountains, drive over the Rabanal, the pass whose unpredictable weather patterns made it so feared among pilgrims, and arrive in the old capital of Leon, where the ‘Sistine Chapel of Romanesque art’ awaits us.

Sunday April 15, 2012

This morning I’d really had it with the rain. I didn’t even want to look out the window. I sent a little prayer to the skies for it please not to rain again. Sure enough, my prayer was answered – it didn’t rain. Instead, we got snow!

A parking lot in the middle of the mountains: Santiago de Penalba. Photo: KW.

Okay, let’s start from the beginning. We had planned to visit a Mozarabic church called Santiago de Penalba, close to Monferrada, a ‘jewel of Mozarabic artistry … high in the Montes Aquilianos’ according to our guidebook. What the guidebook failed to mention was the fact that there was only one road that went the almost 20 kilometres there, a ‘road’ that was much more akin to a mountain trail. It was breathtaking. A mostly unsecured, hugely potholed path that dropped off on the sides into a gaping chasm brought us up to 1,100 metres.

An enchantingly restored village. Photo: KW.

In front of the finely dolled-up village, there was, of course, a pristine parking lot. They were obviously expecting mass tourism. During the trip, we’d joked about whether or not the much-lauded church would even be open, given the number of tourists that this route obviously expected to see. Amazingly enough, it was! The woman in charge told us that photography was strictly forbidden inside the church. She turned on the lights for us – and what we beheld was truly wondrous.

If you’d like to get a feel for the building’s interior, watch this short Spanish-recorded film on YouTube. Click here.

The entrance to the little Mozarabic church. Photo: KW.

At the beginning of the 10th century, St. Gennadius established a monastery in honour of St. James. He later became the Bishop of Astorga, but retired from office in 920 to lead the life of a hermit in Penalba. He died in 936 and his remains were buried in the church, which must have been almost finished at the time. In any case, its construction is dated between 931-937. Perhaps owing to extreme remoteness, the monastery had not established itself as a stop on the Way of St. James. By the 13th century, the monastery had already ceased to exist; in the 16th century, St. Gennadius’ remains were brought to Villafranca. Penalba was forgotten.

The bell tower of the little jewel. Photo: KW.

Today, of course, it’s used as a means of boosting tourism. There were even two bars there, just for us. I ordered the innocuous-sounding regional specialty, lemonade, and was in for quite a shock –this was no ordinary lemonade, but a powerful drink made with a base of red wine and schnapps.

The way back was somewhat faster (and no, not because of the lemonade!). We got lucky and didn’t pass a single car until we turned onto the old country road. Even then, there were more pilgrims than cars. Don’t for a second think that this pilgrimage to Santiago thing is a solitary affair – this was virtually a mass pilgrimage, and within two hours we’d seen more than a hundred of them. Some looked exhausted; others were literally glowing from the inside out. You almost wanted to join them. We waved at anyone we passed, and most waved back. And as we continued to drive further up the Rabanal, we hit a little snowstorm.

On the Rabanal. Photo: KW.

It was like a fairy tale world was unfolding around us. Within a few minutes you couldn’t see the high peaks and the trees and bushes were all covered in white. The pilgrims trudged through the snow with their big backpacks. Our ascent was considerably easier than theirs, and all the same, I was pretty happy I had decided not to have the winter tires changed before we left home.

The iron cross at the top of the pass. Photo: KW.

The Rabanal is 1,500 metres high. There’s an iron cross at the top of the pass, surrounded by a pile of stones. There’s a custom among pilgrims, whereby they bring a stone along with them on their journey intended to symbolize all the sins with which one is burdened. At the Rabanal’s highest point, when the last big obstacle towards Santiago is overcome, the stone is cast among the others under the iron cross. In so doing, the pilgrim is supposed to free himself of all sins during his voyage, to free himself of their weight and burden so that he may proceed through life with greater lightness and ease.

Just so you can get a bit more of a feeling for how incredibly awed we were by this journey, I’d like to play you a snippet from a religious song that dates back to the heyday of the Way of St. James. The Freiburg Spielleyt is dedicated to performing authentic renditions of medieval music. I’m pretty sure that once you’ve listened to it for a minute or so, even the most die-hard non-Christians among you will consider the path to Santiago as a possible holiday option. Click here to hear it.

A first look at the late Gothic cathedral of Astorga. Photo: KW.

Okay, enough with the romanticism. After the pass, the enchanting world of white suddenly turned into nothing more than treacherous, slippery slush. But it continued to lessen as we drove on until we reached Astorga. There, the sun was shining, but somehow still didn’t manage to give off even the smallest shred of warmth.

As seems to be our lot, we were, of course, again too late for the museum (and with it, church entrance as well). Instead we took a sightseeing walk.

There are Roman remains all over Astorga. Photo: KW.

Astorga was originally a Celtiberian centre that was awarded municipal status by Augustus after the conquest of Northern Spain. Under the name Asturica Augusta, the city became one of northwest Spain’s most important centres. Plinius called it an ‘urbs magnifica,’ an important city. It was here that the gold delivered from Las Medulas was further processed. Important evidence of this can be seen in a large Roman hall, sort of an ancient factory, which, sadly, we couldn’t have a look at. It’s part of the Museo Romano, of course, and we’re always too late for Spanish museums.

A portion of the preserved Roman city wall. Photo: KW.

We went for lunch instead (we weren’t too late for that) and visited the Roman city wall, a sight that many of the more southerly lying tourist centres would envy. Still, the well-preserved fortifications paled in comparison to Lugo.

The Episcopal Palace of Astorga, built by Gaudi. Photo: KW.

The Episcopal Palace is probably the city’s best-known structure. It was built in 1889 according to plans by Catalan architect Gaudi. The old palace had been destroyed in a fire, and so the bishop, a good friend of Gaudi’s, asked the avant-garde architect to design a new one. Gaudi didn’t really have the time, so he went about designing the structure without investing his usual degree of thorough and rigorous preparation. My oft-consulted guidebook describes it as ‘neither his most famous nor best work.’ I’d have to agree. Today, it houses the Pilgrim Museum (which we didn’t see … opening times and the like!).

Picture book façade with picture book weather. Photo: KW.

We reached Leon at about 5:00 pm. This time, we had a parador booked, the most beautiful parador of all: the Hostal San Marcos. I was first here about 25 years ago, although not to live, of course!

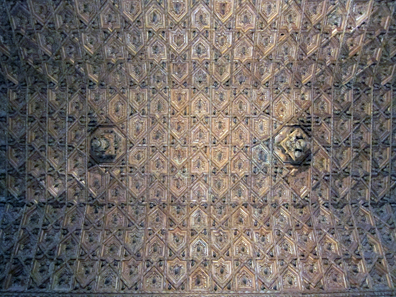

The famous wooden ceiling of San Marcos. Photo: KW.

In those days, I was paying my studies by working as a tour guide of a little agency carrying out journey all over Europe, and during a sightseeing tour we came to the parador. All city tours stopped there at the time to allow tourists to gawk at that amazing wooden ceiling. Ever since then, I’d always planned to stay in this parador one day. And I’ve always been of the opinion that people should do everything in their power to make their dreams come true.

The cloister of San Marcos. Photo: KW.

The Santiago Order had originally set up a pilgrims’ hospital here right next to the bridge, over which a road leads to Astorga. But it wasn’t just pilgrims that were housed here. An information board also reminds people that a concentration camp was based here between July 1936 and the end of 1940 in which up to 7,000 men and 300 women were held prisoner. In total, about 20,000 political prisoners and enemy soldiers from Franco’s supporters are said to have been locked up here.

Alfonso IX, King of Leon 1188-1230. Obol, Leon. From Künker auction 137 (2008), 3419.

But let’s go back to the beginning. Leon was founded as early as the 1st century BC. It takes its name from the legions that were stationed here to protect the region where gold was mined. From the time of Vespasian, Leon also served as the winter camp of the Legio VII Gemina Felix. ‘Leon’ came from ‘legio.’

Alfonso I, the Great, had his residence relocated from Oviedo to Leon. He divided his empire among his sons, and Garcia I was given Leon. His successors were very successful from a military perspective; at the expense of the Muslim principalities, they managed to expand the kingdom of Leon significantly to the south.

Fernando III, King of Castille and Leon 1230-1252. Dinero, Leon. From Künker auction 137 (2008), 3424.

The gentlemen of Leon must have been rather unpleasant neighbours. Still, the Caliphat of Cordoba felt it considerably more economical to pay a tribute to neighbours like these so as to offer some protection from raids. These payments were called taifas, and they made the King of Leon very, very rich – so rich, that he could afford to become one of the most important benefactors of the emerging Abbey of Cluny, in Burgundy.

And Cluny supported him as well. He was provided with unemployed knights in order to advance the Reconquista and was helped in promoting the Way of St. James. This only served to bring the country more prosperity. In 1085, Alfonso VI successfully conquered Toledo, which marked a turning point. The battle against the Muslims was promoted as a crusade. With the assistance of the Catholic Church, the kingdom of Leon expanded and also relinquished its ecclesiastical independence to submit to the pope. In exchange, Alfonso was crowned Emperor of Spain in the year 1135 in the Cathedral of Leon.

Alfonso X, King of Leon and Castille 1252-1284. Noven, Leon. From Künker auction 137 (2008), 3429. Photo: KW.

In 1230, the last King of Leon died. His son, Ferdinand III of Castille, banished his rivals and unified the two kingdoms. From then on, the Kingdom of Leon would be absorbed into Spain, although it remained on the coat of arms.

Pedro I, 1350-1369. Dobla of 35 maravedis, Seville. From Künker auction 218 (2012), 5420.

Leon became an affluent provincial town of little political importance. This had its advantages. It meant that the gorgeous Romanesque and Gothic works of art were preserved, rather than having to make way for modern, baroque buildings.

The portal of the Lamb Gate of San Isidoro. Photo: KW.

Monday April 16, 2012

The next morning, we devoted ourselves to seeing these magnificent artistic treasures. The first road led us to San Isidoro, the ‘Sistine Chapel of Romanesque art.’ Even the exterior is spectacular. There’s a magnificent Romanesque relief above the entrance to the church, on the bottom of which the story of the sacrifice of Isaac is dramatically told. The Lamb of God can be seen above, offering itself as a sacrifice to the world.

A look at the dome of the Royal Funerary Chapel. Photo: KW.

The real treasure can only be reached through a small front hall. You’re not allowed to visit the Royal Funerary Chapel on your own, but instead have to go as part of a tour. The tour is obviously in Spanish, and we found it a bit dry and overly rushed. We could have stood in front of those treasures for hours! First, by the magnificent Romanesque paintings of the church itself (you can note the labours of the months in the medallions on the right hand side of the photo), and then in front of the works of art of the treasury. And who could forget the Reliquary of St. Isidor with its silver reliefs, created in 1065! Or the chalice of Dona Urraca, daughter of King Fernando! We could hardly believe our eyes, and our Spanish guide could sense our excitement. She immediately switched from hurried to delighted. The other tourists were dismissed while we, however, were granted permission to stay here as long as we wanted. We were even allowed back into the pantheon.

Although photography was strictly forbidden, we took a picture nonetheless. I have a guilty conscience over it, but how else could I show you just how well worth seeing San Isidoro is? And if you do ever make it there, be sure to make your enthusiasm known! The guides in Leon are sick of bored tourists, and are eager to show you the wonderful things they have to offer.

The Cathedral of Leon. Photo: KW.

The Cathedral of Leon is also worth seeing, even if it is so French that you hardly feel like you’re in Spain. It really hits home just how close the relationship was between Northern Spain and France during the High Middle Ages.

Main portal of the cathedral with the Last Judgement. Photo: KW.

This is where the Kings of Leon established their palace in the former thermae of the camp of Legio VII. They provided these lands as a building site for a first cathedral. The current construction was erected in the 13th century. The funds came partially from the king –Alfonso the Wise donated a yearly amount of 500 maravedis – and partially from the diocese. In 1258, the bishop allocated the entire earnings of his diocese, and another bishop invested his own private assets. Other essential revenue was provided by indulgences: ‘When money clinks in the cash box, your soul escapes from purgatory.’ Ok, so it wasn’t that easy. In fact, it was quite the opposite – the indulgence was a highly complex construct with careful theological underpinnings, through which the church received voluntary payments from its faithful to be used for joint ventures.

Have you ever noticed: Church portals never depict a soul’s condemnation. Photo: KW.

Indulgences were completely useless without repentance for past sins and the official forgiveness of the church representative. He merely substituted for the final redemption that was a part of every confession. Therefore, the indulgence could also be of benefit to someone who was already deceased. During the High Middle Ages, it became routine for a dying person to confess and repent for their sins. They were forgiven, but because they were no longer able to atone for their sins in life, would have to be sent to Purgatory until everything was ‘cleared’ and they were allowed into heaven. This process was simply intended to hasten an indulgence, nothing more.

A magnificent glass window inside the cathedral. Photo: KW.

The inside of the church is characterized by splendid glass windows from the 13th all the way to the 16th centuries. The large-scale portrayals from the Flemish school in particular show that political ties had changed during the Renaissance. There are no longer French artists coming to decorate the buildings, but rather masters from Spanish-ruled Flanders.

Column capital depicting a camel. Photo: KW.

Right next to the church is the cathedral museum, which apparently is full of wonderful things to see. As usual, the opening times were against us – we only made it as far as the cloister.

German pastry for German pilgrims. Photo: KW.

Here are just two more images from daily life. Pilgrims are an important economic factor in Leon too, especially the German ones. The German bakery turned out to be a great business idea, a place where homesick pilgrims can buy bread, rolls and cake.

Combatting the crisis. Photo: KW.

This restaurant also offers a warm meal for a different kind of clientele. For just 5.95 Euro, customers hit hard by the crisis can get a starter, main course, dessert, bread, wine, water and even a coffee.

That’s enough for today. The next leg of our journey takes us to Burgos, to the tomb of El Cid, and to Santo Domingo de la Calzada where, if you’re not careful, the roast chicken might jump right off your plate and run off, still alive!

You can read all other parts of this diary here.