by Ursula Kampmann

July 26, 2012 – Romans and Celts probably aren’t the first things that come to mind when you think of Northern Spain. At first I dismissed this trip as a one-off journey into medieval times, something we’ve clearly seen enough of already, but I couldn’t have been further off the mark – Northern Spain has so much more to offer. We marvelled at its impeccably preserved Roman city walls, the only Roman lighthouse still in existence, a host of well excavated Celtic hilltop settlements, and a plethora of other incredible sights. We were truly amazed and hope you will be too.

Wednesday April 4, 2012

It all began at 5:30 am at home in Lörrach. Our goal … Western France. As Easter was just around the corner, we hadn’t really decided just how far we’d get on the first day – it would all depend on traffic. After all, we were leaving a mere day ahead of all the regular holidaymakers.

Ultimately it wasn’t the traffic that slowed us down, but the rain. It poured! It was almost as if the skies had conspired to drain themselves of every last drop of water just in time for our departure.

With such horrible weather, we weren’t all that interested in stopping for rest breaks, so were completely exhausted by the time we arrived in Périgueux at about 4:00 pm. We decided to find a hotel and take a little walk in the historic old quarter.

The Périgueux Cathedral. Photo: KW.

There are two centres in Périgueux, and we found a number of good excuses not to explore the ancient part. First of all, it’s diametrically removed from the medieval city, secondly, we were simply too tired, and thirdly, the famed Gallo-Roman Museum with its ambitious architecture would be open for just a few more minutes.

We dutifully noted that Périgueux actually has a Celtic predecessor called Petrocorii, which was expanded and developed by the Romans after the conquest of the Gauls. The new, magnificent city of Versunna must have been quite significant, seeing as it boasted an Amphitheatre that could seat around 10,000.

If you’d like to experience this little walk through the museum for yourself, just click here. There are many photos from the collection.

The Facade of Saint Fronto. Photo: KW.

The Romans left behind a great heritage for their descendants: Saint Fronto, who is said to have acted as the first bishop of Périgueux and about whose life next to nothing is known, except for the fact that he’s said to have destroyed a statue of Mars in Périgueux. Nevertheless, a church was built at the site of his grave on the arterial road outside the Roman city, which explains the two diametrically located centres. It’s developed into an important pilgrimage site by virtue of being a stop on the pilgrim’s path of Camino de Santiago (Way of St. James).

Saint Fronto’s Cathedral is renowned as a fantastic example of romantic architecture of the Middle Ages, with its countless turrets and cupolas and everything beautifully scaled. This is why St. Fronto became the model for Sacré-Coeur in Paris. This horrible roof construction, however, has nothing whatsoever to do with the Middle Ages, but can instead be attributed to the whimsical taste of the architect commissioned for the renovation, Paul Abadie.

Chocolate Galore. Périgueux’s Chocolate Street. Photo: KW.

So, what else is there to say about Périgueux? Anyone with money would be spoilt for choice here – there were realtor signs on the city’s most beautiful Renaissance palaces. Rather than buying a house in Southern France though, we decided to make do with a couple of small bags of chocolate. I had never in my life seen Easter bunnies as imaginative as those in Périgueux’s pedestrian area, where there’s literally one chocolate shop after another. Needless to say, we decided to skip dinner that night …

Thursday April 5, 2012

The sky was still decidedly grey when we woke up in the morning, but at least it wasn’t raining. We went for breakfast and found ourselves surrounded by a group of impeccably styled teenagers who rattled our self-confidence just a little (especially given our early morning crumpled state). Not a single one of the approximately 30 members of the group was even slightly scruffy. Both the boys and the girls looked like they were ready for ‘France’s Next Top Model,’ completely made up, powdered and scented.

We, on the other hand, were completely haggard and exhausted from the previous day’s almost 800 kilometers and still had another almost 400 still to go. The route wasn’t particularly enjoyable. They may call it a highway, but the road from Bordeaux to Bayonne, which passes through what is quite possibly France’s most unattractive region, was actually just a succession of building sites with millions of trucks going through them. We were completely worn out by the time we finally got to the Spanish border.

Of course we managed to get lost on the way to Hondarribia. My GPS was suffering from end-of-the-world syndrome and was feeling overwhelmed. Pulling up the route finder towards the Parador demanded detective-like skills, but by sometime around early afternoon we were finally there.

Parador de Hondarribia. Photo: KW.

To avoid any problems finding accommodation during Easter, we had already booked a room in the Parador de Hondarribia in advance. The Paradores Nacionales are state-operated hotels that, for the most part, are housed in historical buildings. For a hefty price, you can stay in these hotels housed in palaces and monasteries, right in the city centre. The Paradores have been around since 1928 when King Alfonso first established them to promote tourism in the country. In Spanish, ‘parar’ means to make a stop, so a Parador is really just a place where you can make a stop.

Apparently the current economic crisis has had an impact on the Paradores, but we had been advised in Germany just to book for Easter, and then ask about reduced rates once we were actually in the Parador. Whatever the case may be, the Parador de Hondarribia was completely full, which led to quite a few interesting manoeuvres in the not very large parking lot.

The Café of Parador. Photo: KW.

The Parador de Hondarribia is housed within the remains of a 10th century castle built by Sancho II, the Count of Aragon and King of Navarra. There are as yet no coins from this ruler. The Kingdom of Navarra first began to take shape under Sancho’s uncle, Sancho III, he of the lovely epithet ‘The Great,’ who ascended to the throne of Navarra at the turn of the millennium.

Hondarribia castle was just one of countless castles within which the lords of the various northern Spanish empires entrenched themselves. Sancho II was able to maintain a decades-long alliance with the Caliph of Cordoba. It was only when this Caliph died in 976 and a weak successor allowed Al-Mansur to seize power of the government that Hondarribia became a fortress against Muslim raids. Sancho was still banking on negotiations. Al-Mansur is said to have spared his kingdom because the King of Navarra had relinquished one of his daughters to him.

Coat of Arms in Parador. Photo: KW.

In any case, the harsh exterior can be traced back to a renovation made by Charles V. After this, Hondarribia saw a whole host of Spanish rulers, from Juana la Loca right up to the many Philips. Later on, Napoleon began to covet Hondarribia and had the castle seized. The French then ruled here from 1808 to1813.

Sadly, we didn’t get the chance to make use of Hondarribia’s gorgeous grounds, as it started raining again. But we still had over two weeks ahead of us … no sense getting rattled by a bit of rain at the outset!

Friday April 6, 2012

The first thing we saw when we woke up was the oppressively grey and drab sky – fitting, perhaps, for a fortress, but not so much for planning an outing. We decided to visit San Sebastian, known in Basque as ‘Donostia.’

Testimony from the Grand Age of Donostia in the 19th Century. Photo: KW.

San Sebastian takes its Spanish name from a monastery in honour of St. Sebastian, who we only first hear about in 1014. Back then, Sancho III – the ‘Great’ one who struck the first coins – presented the small monastery of San Sebastian, with its large estates of apple trees (the region is famous for its cider), with the gift of the Abbey of Leire.

In the 13th century, the city became a significant port that was settled primarily by the Gascons, who came from nearby Bayonne. As a massive fire destroyed the entire city centre in 1849, there’s nothing left to see here from the Middle Ages.

1813 Medal by Webb and Mills of the capture of San Sebastian by the English and Portuguese. From auction MMDe 24 (2007), 1312.

The structures of the Early Modern Age were completely obliterated in 1808 by destruction caused by battles between the British and the Portuguese and also by the Bonapartists. Incidentally, the Basque name Donostia also comes from St. Sebastian. Rather than using the term ‘Saint’, the Basques describe their protector as ‘done,’ from the Latin ‘domine,’ and when combined with ‘done’ Sebastian became ‘Donostia.’

La Concha – a stunning bay. It would have been even more stunning with a bit of sun. Photo: KW.

As such, the new cityscape was a tabula rasa. The king’s widow, Maria Christina, had come to San Sebastian every summer since 1885 to enjoy the gorgeous bay with its wonderful sandy beach, now appearing before us through light drizzle.

She brought along her minions and everyone who wanted to become one. They built a casino and San Sebastian quickly became a popular tourist attraction. Mata Hari, Leon Trotsky, Maurice Ravel, the Romanovs – they all relaxed before this magnificent backdrop. By the way, the city also became the stronghold of the ETA. The foundation stone was laid in the Spanish Civil War. In 1936, Franco’s followers captured the city, and Basque nationalists, anarchists and communists were all among the casualties. Three hundred and eighty people were put to death and 40-50,000 residents left their city. When a group of young Basques founded the ETA in 1959, they could rely on the support of the Basques of Donostia.

The Maritime Museum doesn’t just have an aquarium, it also offers a wealth of economic history. Photo: KW.

The rain drove us, like hundreds of families with more than two children, to the shelter of the Maritime Museum, which also has an aquarium. It was very crowded, but we reassured ourselves that the museum would likely be empty by 2:00 pm, since Spaniards tend to eat lunch at home.

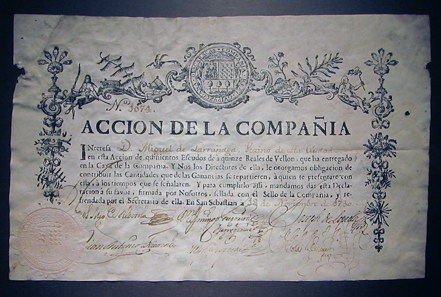

Share from a Basque Trading Company. Photo: KW.

The families actually weren’t that bad. They rushed through the museum halls, while we discovered all sorts of exciting things – like a share from a trade organization, the ‘Real Compania Guipuzcoana de Caracas,’ which had the monopoly on all goods shipped between Spain and Venezuela. The company was established in 1728 as competition to French and British trading companies. It was very successful and brought its shareholders a small fortune.

The Slaughtering of a Whale. Photo: KW.

Whaling was just as important for San Sebastian, as blubber was a cheap alternative to expensive candles. Furthermore, parts of the whale were made into the following products: soap, ointments, soup seasoning, paints, gelatin, cooking fats and shoe- and leather care products. Nitroglycerin was partly composed of whale oil. And then there was also the amber for the perfume industry and the plates of the blue whale for boning corsets.

The Basques were the first to practice whaling professionally. A first record of whaling is said to have come from as long ago as the year 670 (sic!). Whales were definitely hunted in San Sebastian in the year 1150, as evidenced by a charter from Sancho the Wise, which refers specifically to products acquired through whaling.

Hunting was done most notably in Biskaya, but in the 16th century, in particular, there were many dubious theories about Basque whalers reaching America long before Columbus. The whales in this region were, however, wiped out at latest at the beginning of the 19th century. By this time, other nations had also discovered the lucrative trade, so the Basques were therefore just one of many nations that destroyed the whale.

Tunnel under the Shark Tank. Photo: KW.

Next up after the historical exhibition was the aquarium, which was so full of screaming, running, grouchy children that it was unbearable. It didn’t get any better by midday, so we fled. Good thing too, as in the meantime the line had become about a hundred families longer. They were standing well out into the street, hiding under umbrellas.

We drove straight to the hotel. It was raining so heavily that we lost interest even in going for a walk, so we sat snugly in our room and read instead. The nice weather was sure to come … sometime …

The next leg of our journey took us to Covadonga, which, according to tradition, arose from medieval Spain. Join us as we visit the new Oviedo archaeological museum, or take part in an Easter Sunday procession, just a couple of the highlights of the second leg of our tour of Northern Spain.

You can read all other parts of this diary here.