by Ursula Kampmann

June 23, 2011 – The first stage of Ursula Kampmann’s journey to Greece takes her from Venice to Igoumenitsa and Nicopolis up to Ambracia. Hidden mosaics and fateful padlocks render the area’s visit quite difficult. But there is enough left to discover!

Day 1, June 10, 2011, The passage

For those who want to forego a strenuous tour through the states of former Yugoslavia there is an easier way to get oneself and one’s car to Greece: the ferry.

Minoan Lines ferry. Photograph: KW.

Admittedly, one doesn’t feel like Odysseus when taking these giant colossuses of modern shipping. More like a tiny and insignificant part of the global tourist industry. Hundreds of cars, trucks and camper vans are transported into the ferry’s belly, accompanied by enormous shouting and pushing. Anyone being surprised at that pushing (after all, the ones entering the ferry last are the ones who can leave it first) may be informed that the economic tourist naturally doesn’t allow himself a cabin at the price of 100 to 150 Euros (depending on the time of booking).

Arcadian camping scenery on board the Europa Palace. Photograph: KW.

Being a true adventurer, one makes oneself at home, with tent, airbed and sleeping bag to the effect that on the entire ship sleepers are to be found who marked their territory with heaps of luggage. (What do you think? I don’t fall into the category of “adventurer“ anymore. I had a cabin at my disposal.)

Entry to the Grand Canal, in the foreground of the picture, to the left, the customs station for luxury goods. Photograph: KW.

The dear fellow travelers are not the only attractions such a giant, swimming garage has to offer. Right through Venice, the navigation channel, marked-out by wooden posts, leads the way out the lagoon. The Vaporetto station Zattere is passed which got its name from the logs that used to be shipped here roughly half a millennium ago to be used for building ships as well as houses. And there is the gorgeous customs station for luxury goods sitting enthroned right at the left of the entrance to the Grand Canal. That was convenient. The warehouses of the merchants dealing in luxury goods were situated at the Rialto. The ships transported the cargo there; on their way they inevitably passed the customs station where the Republic of Venice made sure it got its share of the merchants’ wealth.

The Zecca of Venice. Photograph: KW.

Last highlight of the passage through the lagoon is the Piazza San Marco with all the national emblems of a center of power: the Doge’s Palace being the seat of government with St Mark’s Basilica, the chapel of the Doge; the two columns in the old harbor, the gallows square of the Republic, and, of course, the mint, the Zecca, which the Zecchini got their name from.

Day 2, June 11, 2011, Lodging in Parga

Roughly 22 hours – that was the duration of the passage we took from Venice to Igoumenitsa with the Europa Palace of Minoan Lines. Time passed by rapidly. It is possible, to one’s taste, to watch the fellow travelers or the coastlines and islands passing by. We passed by Corfu, and, as early as lunch time, arrived at Igoumenitsa.

Having spent hours on deck, all drivers apparently bottled up quite an amount of energy. Just like racing drivers they jump into their drivers’ cabins, make their engines roar and race out of the harbor to get to the beaches of Greece as quickly as possible.

Nobody stays long in Igoumenitsa. There is really nothing attractive to see there. The city is only relevant as the starting point of the new big freeway, the “Egnatia” which, admittedly, doesn’t follow exactly the same line as the Roman Via Egnatia, but at least carries its name. The street leads from Thessaloniki and Kavala to the freeway from Belgrade via Sofia to Istanbul.

Our favourite bay on the coast of Epirus. Photograph: KW.

We didn’t take the fastest way to the East. Already prior to our departure, we had decided to spend some time in Epirus, in Parga, more specifically in an incredibly quaint bay just before Parga which is greatly influenced by tourism. However, we got disappointed. The Greek calendar marked a feast day, and Parga and its surroundings were crawled, not the tiniest space was available anymore. There was no sign of any kind of economic crisis preventing people from bridging the feast day and holidaying at the seaside. In the end, however, we were lucky in the circumstances. For the Greeks are no different than the average Europeans who like to resort to the seaside on holiday. The coastal strip was utterly overcrowded which meant on the other hand that there were enough rooms available in the hinterland, at a few kilometers’ distance only, where we took refuge for a couple of nights and made it our base camp for the exploratory trips through Epirus.

Day 3, June 12, 2011, Nicopolis

Epirus is a rough mountainous area with some elevated, difficult regions. It is no wonder, then, that many important cities orient themselves more to the sea. A case in point is Nicopolis, whose name is well-known not only to every numismatist but to anyone dealing with ancient history.

Augustus, denarius, 15 B. C., Lugdunum. Rev. Apollon of Actium with lyra and plectrum. RIC 171a. From auction Gorny & Mosch 186 (2010), 1856.

After all, it was at near-by Actium where the decisive battle between the fleet of Octavian and Cleopatra was fought.

From the ruins of the city of Nicopolis, the Gulf of Ambracia can be seen. Photograph: KW.

The city’s correct name is “Actia Nicopolis”. It is situated on a peninsula between the sea and a huge gulf, the Gulf of Ambracia. It was founded in 30 B. C. by Octavian. Thanks to royal support, Nicopolis soon became the most important center of Epirus.

Map of Nicopolis. Photograph: KW.

Octavian had granted Nicopolis the rights of a free Greek city. That, however, was not enough to keep the Epirotes from settling in the new center. To populate the city as fast as possible, Ocatavian forced large numbers of inhabitants of the surrounding cities of Epirus and Arcanania to resettle. Nicopolis, therefore, virtually was an important major city from the moment of its foundation.

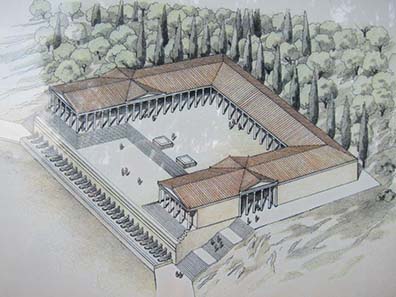

Reconstruction drawing of the victory monument of Augustus. Photograph: KW.

Octavian spent a lot on the lavish layout of Nicopolis. He invested his booty from the Battle of Actium in the construction of numerous representational buildings of which today only the victory monument of Augustus can still be seen. It was here, as the visitor proficient in ancient history happily recalls, where Octavian had his headquarter located during the Battle of Actium, where he awaited at a safe distance if his military commander Agrippa would successfully pull the chestnuts out of the fire for him. The layout of this magnificent monument is well-known.

Reconstruction drawings depict a site of 40 x 40 m whose front was decorated with an honorary inscription and the ram bows captured at Actium.

A typical Greek sight: an entrance secured by solid locks. Photograph: KW.

Does reality match up with that? No idea, really. The entrance to the excavation site was secured by a solid lock. Opening hours? What’s the point since only tourists tired of beaches are interested in that old stuff.

Another typical Greek sight… Photograph: KW.

Solid locks are often encountered in Nicopolis. Like, for example, at the front of the local museum that is said to house some interesting objects from archaeological excavations.

Basilica of Doumetios. Photograph: KW.

At least, the Bishop’s Palace and the Basilica of Doumetios, which is absolutely worth seeing, were accessible. That takes us already to early Byzantine times.

Nicopolis, after all, had quickly displaced the other important city of Epirus, Ambracia, from its position. Since A. D. 67, Nicopolis was capital city of the Roman province of Epirus. That remained unchanged until Byzantine times, and Nicopolis became bishop’s see.

Justinianic city wall. Photograph: KW.

Nicopolis must have been wealthy. The visible wealth in any case attracted begrudgers. In 397, the Visigoths attacked Nicopolos, in 475 the Vandals came led by Genseric, and in 551 the Visigoths again invaded the city, this time led by Totila.

Not even the city wall, built in 540 by Justinian and surrounding roughly one quarter of the former territory, could protect the city against that last invasion.

In the city a number of Byzantine churches were erected of which remains survived until the present day: the Basilica of Alkyson (make an educated guess – yes, you’re right: closed) and the one of Doumetios (a miracle, open).

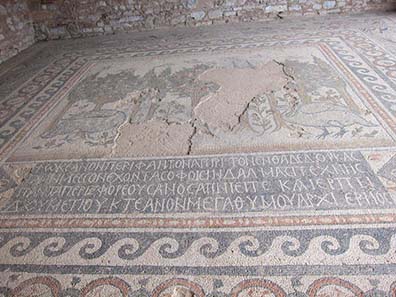

Mosaic floor of the Basilica of Doumetios with the inscription of the dedicator. Photograph: KW.

This basilica was built in the second half of the 6th century. It deserves mention because of its mosaic floors that can actually be viewed. One of these shows the dedicatory inscription below a central motif with the earth as pastoral setting where fruit-bearing trees and lush plants grow providing a home for peaceful birds.

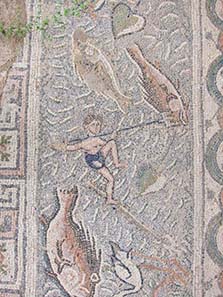

Mosaic floor of the Basilica of Doumetios. Photograph: KW.

That scenery is surrounded by the ocean with giant lively fish that are hunted by small fishermen.

Mosaic floor of the Basilica of Doumetios. Photograph: KW.

Another floor shows two civic officers in the middle, surrounded by quite lively hunting motifs.

Hidden mosaic floor of the Basilica of Doumetios. Photograph: KW.

The entire basilica was covered with mosaics once. To protect the parts not currently exhibited they are covered with soft fleeces which are visible everywhere underneath the layer of pebbles.

That concludes our visit to Nicopolis. By the way, the city, whose demise started in the 13th century, many a times became the place where military conflicts between “East” and “West” were decided. In 1396, Sultan Bayezid I repulsed an army of crusaders led by King Sigismund. In 1798, the French occupation successfully fought Ali Pasha. And in 1912, the Greeks obtained the decisive victory over the Ottoman army so that Epirus and Greece were united. By then, however, Nicopolis had seized being a significant city. It lost this position to near-by Preveza which appeared in the sources for the first time as early as 1292.

Day 4, June 13, 2011, Ambracia

“Arta with its historically and artistically important buildings is a buzzy city, which by now is oriented towards tourists as well, with a population of approximately 30,000.” says a guidebook written in 2003. “Buzzy” holds absolutely true. Arta is a local center attracting people from the entire surrounding area to shop and dine. If that goes well with tourism is a different matter. Narrow alleys, the lack of parking space and the Greek driving mentality, that takes some getting used to, makes a visit to the city an interesting experience.

A look at present-day Arta, ancient Ambracia. Photograph: KW.

When looking at modern Arta, nobody would think that an ancient city is hidden here, founded as early as 645 B. C. by Gorgos, a son of the Corinthian tyrant Cypselus. The ancient city is Ambracia which the great gulf got its name from that shapes the landscape of Southern Epirus. Ambracia, protected by the course of the Arachthus River, hence was conveniently placed as regards transport facilities in the fructiferous and water-rich lowlands. It comes as no surprise that the city turned into a powerful center, both militarily and economically.

Ambracia, Stater, c. 404-360. Av. Pegasos r., below A. Rev. Head of Athena with Corinthian helmet l., in front of it snake coiling round a turtle, behind that nude hero. Cal. 86. From auction Gorny & Mosch 155 (2007), 87.

Ambracia always played a role in big politics. During the Persian Wars and the Peloponnesian War it fought alongside the Spartans. Sparta, in turn, aided Ambracia when in 430 B. C. a fight broke out between the city and Argos Amphilochicum, whereas Athens supported the latter.

Ambracia. Stater, 360-338. Pegasos l., below A; under the trunk snake coiling round a turtle. Rev. Head of Athena with Corinthian helmet l., above attacking bull. Cal. 4/2. From auction Gorny & Mosch 151 (2006), 153.

In 342, Philipp II tried to seize Ambracia. His first attack was successfully repulsed, but soon thereafter he nevertheless gained control over the city. We know this because Ambracia repulsed the Macedonian garrison in 336, when Alexander came into power.

Pyrrhos is omnipresent in Ambracia’s cityscape, not only with a street of his own but also with a statue. Photograph: KW.

Under Pyrrhos, Ambracia again flourished. The Molossian King decorated the city as his residence. Most of the art works created in that time were brought to Rome in 189 B. C. M. Fulvius Nobilior transported 1,000 statues to the Eternal City after the Ambracians had given in after being under siege and had become happy citizens of the Roman Empire.

The founding of Nicopolis in 30 B. C. cost a major part of Ambracia’s population. In addition, it had got a rival in close proximity, supported by the emperor. The words of Pausanias come as no surprise, then, who wrote that on his visit he saw the once so important city deserted.

The Metropolitan Church Panagia Parigoritissa. Photograph: KW.

In the 11th century, however, Ambracia re-appeared in history, under the name Arta. All those magnificent buildings actually date to that era, like the Metropolitan Church Panagia Parigoritissa.

It was erected when Arta was capital of the Despotate of Epirus.

Map of the Despotate of Epirus. Source: Wikipedia.

The Despotate of Epirus was founded by Michael Angelos Komnenos Doukas, illegitimate son of John Angelos Komnenos, who was the son of Emperor Alexios I Kommenos and hence cousin of reigning rulers Isaac II Angelos and Alexios III Angelos. After Constatinople fell during the 4th Crusade in 1204, Michael managed to take up a position of all-round defence in Arta of which he gained control without meeting much resistance in that time of transition.

Epirus hadn’t suffered yet from the Crusade and was still wealthy; thanks to the many refugees from Constantinople the small empire at the periphery gained intellectual and economic resources making the city far more than a mere province’s capital. For a short period of time, the Despotate of Epirus became the most important empire on the Balkans.

It was here where the Byzantine art survived the Fall of Constantinople. The result is present everywhere in Arta, or more to the point it would be, were the churches easier to find in the warren of houses.

The gorgeous interior of the Metropolitan Church. Photograph: KW.

Relatively easy to find was the Metropolitan Church Panagia Parigoritissa that Nicephoros I had being built. And it was open, at least for three minutes. After that, the person in charge made clear signs that he had to close the building (rule no. 1 for travelers to Greece: there is a comparatively big chance that a building will be closed at 3 p.m.!).

Pity we hadn’t more time for the interior which was hugely impressive. The whopper that appears rather square-shaped when seen from outside, is actually a tower of stacked bricks in the shape of ancient columns. They most possibly come from Nicopolis which, when Arta or Ambracia, respectively, experienced its second bloom, had already seized to exist.

The Doric temple of Ambracia. Photograph: KW.

There are hardly any ancient ruins left in Arta, except for a (closed) Doric temple from the early 5th century.

The famous Bridge of Arta. Photograph: KW.

In Arty, leisure, recreation and tranquility can only be found at one single place, at the foot of the famous bridge of the city which – as the guidebook reveals – is often sung about in a Greek folk ballad (unfortunately, my expertise of Modern Greek isn’t profound enough to verify that statement).

Plane tree next to the Bridge of Arta. Photograph: KW.

In any case, several quaint cafés next to the bridge offers a beautiful place to recreate, under a giant plane tree which may well have already stood there at the time when, in 1603, a wealthy merchant had the existing building erected at the place of an older bridge. Being almost 150 m long, the Bridge of Arta is the longest bridge from Ottoman times in the whole of Greece.

The Castle of Parga, in the foreground beach life. Photograph: KW.

We had planned on spending the evening in Parga, once an important harbor that was part of the Empire of The Serenissima from the early 15th century until the fall of the Republic of Venice in 1797. A magnificent castle is located there one can get to after strolling a nice path. At least, that was how we recalled it. What we didn’t anticipate were the thousands of tourists filling the village’s cafés, restaurants and souvenir shops. When recalling Parga as quaint fishing port twenty years ago, one is inclined to wonder how much tourism a village can take.

The inhabitants of Parga, however, charge well for the destruction of their village. Every price is twice as high as in the surrounding area. Anyway, we didn’t even stay half an hour in Parga.

That’ll be it for today. More is coming on next week. We visit the Oracle of the Dead at Ephyra, bathe our feet in the Acheron, River of the Dead, and visit distinguished numismatist Katerini Liampi in Ioannina.

You can read all other parts of this diary here.