In Italy, people were convinced that – even though they might have won the First World War (1914-1918) – they had lost their peace. And indeed, there was striking evidence for this: Italy’s participation in the war had been dearly paid for with 600,000 casualties, staggering national debt and a severe economic crisis. Moreover, Italy’s imperial dreams had not come true at the peace conference in Versailles: they only got South Tyrol and a few small territories, but not the popular Dalmatia or the coastal town of Fiume. The catchphrase of a “vittoria mutilata” (mutilated victory) circulated through society. People suffered from frustrated nationalism, hunger, unemployment and enormous inflation.

Against this background of an economic and spiritual crisis, a militant socialist movement unfolded. Workers enforced the eight hour day, there were strikes, street fights, factory and land occupations. Government and parliament were unable to remedy the loss of public order. Anyway, the Socialists and the left-wing Catholic People’s Party, founded in 1919, had been the strongest parties in the parliament since 1921. The outbreak of a Russian-style communist revolution seemed to be imminent.

Benito Mussolini: How a Journalist Became Duce and Prime Minister

In this environment of fear and violence, a former far-left journalist saw an opportunity to rise to power. In 19191, Benito Mussolini switched sides and founded his “fasci di combattimento” fighting force. The name of the fasci derived from the Latin “fasces” – a bundle of rods with an axe in the middle, which represented the authority of high officials in ancient Rome: in this way, Mussolini tied in with the tradition of the Roman Empire.

Wherever workers were striking in factories, wherever peasants occupied territories, Mussolini’s black-shirted fascists appeared. They systematically started to smash parties, trade unions and local left-wing associations. They murdered, robbed, looted and sacked. Law and order no longer seemed to apply in Italy; political crime became part of everyday life.

Nevertheless, many social groups – industrialists, big landowners, mafiosi, citizens and conservative Catholics – considered Mussolini and his fasci to be the lesser evil compared to the socialists and communists. At the same time, Mussolini, as “Duce” of the fasci, knew how to justify these violent acts by means of populist rhetoric. His catchy slogans appealed to the emotions of the people and fascinated them. More and more people quickly joined the fascists.

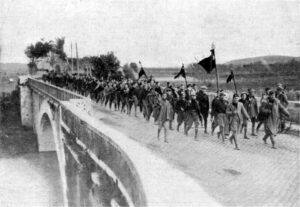

In October 1922, Mussolini organised his legendary “March on Rome”: tens of thousands of fascists Blackshirts marched on the Italian capital coming from different directions. Faced with this threat, the liberal government pleaded for a state of emergency to be declared. To prevent a violent coup, the terrified King Victor Emmanuel III (1900-1946) appointed Mussolini Prime Minister of Italy (1922-1943) and entrusted him with forming a new government. This marked the beginning of Italy’s history as a totalitarian state. And in Germany, a certain Adolf Hitler set out to imitate the Duce and his demagogic rhetoric.

In the first days of August of 1941, the demand for means of payments increased significantly throughout Europe: World War One had begun – troops had to be mobilised, weapons and supplies had to be procured. To be able to spend money quickly, the central banks of the countries involved in the war were no longer obliged to redeem paper money for gold. In Italy, however, this suspension was not necessary because the paper lira had already been circulating in the country for decades.

By the end of the war in 1918, the paper lira had lost a fifth of its value. But its true depreciation only began after the end of the war: by 1926, the value of the lira had decreased by 50 percent – compared to its value after the war! It was not until 1927 that the Italian currency stabilised: at that time, 4.7 new lira were worth one pre-war lira.

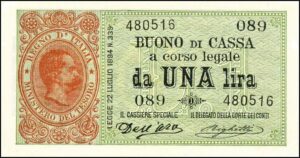

As early as in 1922, there were no small coins in circulation in Italy anymore, only tokens with the words “BUONO DA L. 1” and “BUONO DA L. 2” (voucher for one and two lira, respectively) – although they had been issued by the state.

And yet, the depreciation and the lack of circulation money were not the only things that troubled Italians after the war. The sudden halt of the war industry and the return of soldiers from the front caused unemployment figures to skyrocket. But even many of those who still had a job suffered from poverty: due to inflation, the cost of living in 1918 was more than 2.6 times higher than it had been before the war.

After the hardships of war, Italians were even more disappointed about the economic misery. Strikes and hunger revolts shook up the country, and for a while it seemed like a Russian-style revolution could also unfold in Italy. In the north of the country, workers occupied factories; and peasants annexed uncultivated land in the south. Eventually, the Blackshirts under Benito Mussolini put a violent end to these events. In 1923 – on the one-year anniversary of the fascists taking over power – Italy issued aluminium coins of 20 and 100 lire featuring the fasces, the bundle of rods on the reverse.

By the way, Mussolini was not the first to wipe the ancient dust from the fasces: during the French Revolution, the fasces was considered a symbol for gathering liberal forces; it was depicted on 1904 French coins as a symbol for the republic. American coins also depict the bundle of rods, for example the Mercury dime of 1919. But just like everything, there are two sides to the fasces symbol too: the rods and the axe do not only represent the republican bearers of state power but also the exercise of power. In fact, people were beaten with rods and the axe was used to execute death sentences. This is the aspect Mussolini’s imagery focused on.

The coins that were later issued by the fascist regime bear two dates: Arabic numbers indicate the year according to the Christian calendar, and Roman numerals the new fascist calendar. Both numbers can clearly be seen on the reverse of this 50 lire piece of 1931.

In the next episode, we will shed light on the relationship between the Church and the fascists and take a close look at an Italian leader who was a great fan of numismatics.

Here you can find all parts of the series “From Lira to Euro. Italy’s History in Coins”.