by Björn Schöpe

December 13, 2012 – The third Indiana Jones sequel featuring Harrison Ford as adventurous archaeologist was a great box-office success indeed. ‘The Kingdom of the Crystal Skull’ is the story of an object that is not only reported to be ancient but also to have magic power. At least the economic aspect was magic: the film grossed nearly $800m shared between Paramount Pictures, Walt Disney Studios and Lucasfilm. Now the Mesoamerican state of Belize claims a portion of this money. On what basis the state has come to that idea seems rather bizarre, anyway …

Harrison Ford during the last Indiana Jones film. Photo: John Griffiths / Wikipedia. http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.0/deed.de

Jaime Awe, director of the Institute of Archaeology of Belize, filed the lawsuit in Illinois on behalf of the State of Belize. According to their view things happened as that: In 1924 British Frederick Albert Mitchell-Hedges and his daughter Anna found an ancient crystal skull in a Maya temple in Lubaantun exporting it illegally into the USA. Following her father’s death the daughter made money out of the skull by showing it on pay-per-view basis. After all it was allegedly an object possessing magic power that served once to the Maya priest to doom men who were to die soon after. Mr Mitchell-Hedges had spread these rumours in the first edition of his autobiography.

It is said that the replica used during the Indiana Jones shooting was made exactly after this crystal skull (also known as ‘Skull of Doom’ because of its alleged properties). Since years Belize has demanded the return of that ‘national cultural object’ adding now claims on the film’s revenue because the replica was used without its authorisation. However, it is doubtful whether the claimants had done any thorough research on the facts. Let apart the legal details (and the question whether this replica was really taken after that crystal skull) the verifiable facts give rise to doubts regarding this interpretation, to say the least.

Very similar to the Mitchell-Hedges skull is this crystal skull in the British Museum. Photo: Rafal Chalgasiewicz / Wikipedia. http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/deed.en.

Besides the so-called Mitchell-Hedges skull we know similar skulls preserved in the Smithsonian Museum, in the British Museum, and in a Museum in Paris. All of them bear the label: ‘fake’. No hints from Maya myths or images made by the pre-Columbian peoples indicate that they ever manufactured objects of this kind.

All skulls, comprising the Mitchell-Hedges skull, were tested recently applying modern high-end technologies. And the verdict was unanimous: They were clearly made in the nineteenth or twentieth centuries with metal instruments definitely unknown to the Mayas or Aztecs.

When asking where these items shrouded in mystery may come from, we get to the second part of the argumentation. Most probably Anna Mitchell-Hedges lied. Indeed she contradicted herself in her description of how she allegedly found the crystal skull. The scene of young Anna discovering this object below a collapsed altar in a Maya temple in Lubaantun, as cited by Jaime Awe, is only a romantic version among numerous others. Obviously she was not really sure about what sounded most convincing or appealing. Her father did not mention this discovery in his autobiography, anyway, and no other member of their expedition could recall it either. On the contrary a very commonplace receipt, dated 1943, proves that Frederick Albert Mitchell-Hedges bought the skull in England from Sydney Burney, a London art dealer and collector.

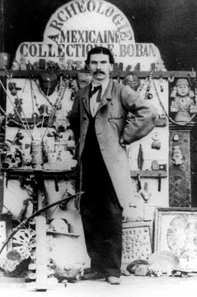

The French antiquarian Eugène Boban ordered the manufacture of the skulls. Before 1867. Photo: Wikipedia.

The Smithonian skull was sent to the museum anonymously by post in 1992. The traces of the British Museum skull and the Paris skull, however, lead demonstrably to one person: French antiquarian Eugène Boban. Boban was the official archaeologist of the court of Emperor Maximilian I of Mexico. Besides that occupation he sold not only pre-Columbian antiquities but also these ancient crystal skulls – which he probably ordered to be produced in the German centre of crystal workshops in Idar-Oberstein.

The lawyer who represents Belize at court believes the crystal skull to be a Maya object like the other skulls as well, all stolen from Belize. Hence they are to be considered property of the people of Belize. We can only speculate whether Belizes’ chief archaeologist Awe is actually convinced of this allegation or if he only wishes to represent his country successfully in this matter – in any case his behaviour as a researcher appears dubious. It is simply incomprehensible why Belize claims rights on an object probably made in Germany out of Brazilian quartz on order of a French antiquarian and sold in Mexico to a Briton whose daughter has kept it in the USA since. The same goes for why Belize claims a portion of the film’s revenue because of a replica allegedly take from that object in discussion. In one point, however, the lawyer is absolutely right: there is no need for further tests on the skull after those conducted recently. The facts are clear.

Extensive information with many notes offers the Wikipedia article on crystal skulls.

On the BBC travel site you can read a nice article on Belize. The author refers to the mysterious crystal skulls, too.

FoxNews has re-published a detailed LiveScience article on the tests of the skulls and this absurd law suit.