by Ursula Kampmann

translated by Teresa Teklic

July 10, 2014 – Akragas has been listed as UNESCO World Heritage Site since 1997. This distinction attracts tens of thousands of trampling tourists daily who populate the Valley of the Temples. Including us.

Easter Monday, April 21, 2014

We set off to Akragas in the most perfect weather. We again passed Castelvetrano and were thus also close to Selinus, but the memory of our previous rainy visit effectively curbed our enthusiasm about a follow-up. Instead, a small church had caught our attention, Santissima Trinità, somewhere near Castelvetrano. Getting there looked easy enough on the map. It wasn’t quite as easy once we got to Castelvetrano though. We circled the city centre once, twice, always lured by the brown signposts promising the way to SS. Trinità di Delia. At some point we had enough and decided to ignore the brown signposts. And – surprise! – we ended up on a road that led us straight to the church.

Santissima Trinità, a jewel from Norman times. Photo: KW.

But of course it didn’t stop there. Next, we found ourselves facing a more than head-high wall, which completely blocked our view. I started to look around and, after some 15 minutes, discovered a gate, entrance to a kind of holiday resort. No trespassing! a sign warned, so I entered. A man, who’d obviously got out of the wrong side of bed that morning, tried to shoo me away. When I started to ramble on about “Church Santissima Trinità di Delia”, “where?” and “visit” in Italian, he had mercy and allowed us to open the gate, secured with a heavy padlock, which guards one of the treasures of Norman architecture.

View of the dome. Photo: KW.

The church is positively tiny, only 10 m by 10 m. But the park surrounding it is bathed in light and embellished with massive trees and a field of blooming flowers. Plus, we were the only visitors to enjoy this treasure (apparently other tourists had been misled by the brown signposts).

The church was among the first ever built by the Normans on Sicily, presumably in the late 11th, early 12th century. It formed part of a monastery and shows Byzantine and Islamic influences.

Tomb of Giuseppe Saporito. Photo: KW.

The impressive tombs, however, are from the 19th century, not the Middle Ages, built for members of a rich Sicilian family that made a fortune in corn trade. Giuseppe Saporito, whose tomb is depicted above, was gabellotu, i.e. he rented land from the old aristocracy and leased it to Sicilian peasant farmers. He provided protection as well as land. Men like him were the law in Sicily, at least in the 19th century. Many historians today assume that the gabelloti were the predecessors of the Mafia’s godfathers.

Be that as it may, Giuseppe was rich enough to make use of a law passed on October 10, 1862, that nationalized all Church property on Sicily and allowed it to be sold at more than reasonable prices. Among them was the beautiful Norman church Santissima Trinità, including the attached monastery. If it was up to me, I’d take down the other brown signposts in Castelvetrano too, so the heavenly quiet of this place won’t be disturbed by other visitors.

We drove on to Akragas and I grew increasingly tense. On previous holidays, we had always looked for accommodation on site. Then we realised that this didn’t work on Sicily. All of the pretty apartments are so far off the main streets that there’s not a chance to discover them by pure coincidence. So I’d used the internet to make reservations and booked a room in Akragas during our stay in Balata di Baida. This time not in an agriturismo, but in a common hotel. The only problem were the rather sketchy directions I’d jotted down. After all, it couldn’t be that hard to find a hotel in this small city. That’s what I thought. And rethought once we drove into the gigantic Porto Empedocle. Turns out my memory of a cozy Akragas was precisely that – a memory and figment of my imagination.

So we cruised around. The hotel we did not find, instead an accommodation of the Adventists. Or was it the New Apostolic Church? Either way, they sang their chants loud enough for us to hear in the streets. When we arrived at the beach we decided not to take a dip in the Mediterranean on the hotel’s own beach, as advertised online.

At last I had enough and went into one of the other hotels to enquire after ours. What happened next was helpfulness in a typically Sicilian fashion: instead of being annoyed, the receptionist jumped up from his seat and came running to my help, showing me exactly which turn to take at the next traffic lights. In the end, finding the “Antica Perla” really wasn’t too difficult. Again we were received warmly. The rooms had a Sicilian flair. Beautiful, because newly built, but who knows how long they’d stay this way … The wind played a song on our door, loud enough to disturb our sleep.

So in order to sleep, we’d have to be fairly tired. To help that matter, we treated ourselves to a dinner of gigantic proportion in the Pizzeria Mediterranea. Although this Pizzeria didn’t resemble the German use of the word in the slightest. It was a wonderful restaurant with the finest of Sicilian delicacies. Crowded with equally gigantic family clans, spanning several generations, which convened here to celebrate Easter Monday. We feasted on four courses, drank more Prosecco and wine than intended, were taken excellent care of by our “cameriere”, our waiter, and thanked God that there was no roadside breath test on the short way from the restaurant to our hotel …

Tuesday, April 22, 2014

Today’s plan was to see Akragas. At breakfast we got a little taster of what to expect later that day. We shared the hotel with three other travel groups. One of them Austrian, which meant that we (unfortunately) understood everything they said. The smartest comment in that conversation was that, strictly speaking, they didn’t have to visit the Valley of Temples anymore as they’d seen everything already on the pictures decorating the breakfast room’s walls. Brilliant idea, if you ask me.

The odeon or ekklesiasterion. Photo: KW.

As it looked like rain, we decided to visit the Museum of Akragas first. It can be reached by crossing the odeon – ekklesiasterion in Greek, i.e. the venue the ekklesia, the people’s assembly –, and the so called Oratorium of Phalaris.

The so called Oratorium of Phalaris. Photo: KW.

It is called oratorium because the insignificant little temple, converted into a tomb in the 1st century AD, used to be a monastic prayer room long ago, and Phalaris comes into play as an attempt to enhance the fascination factor for tourists of this otherwise fairly unremarkable building. And the tyrant Phalaris is pretty fascinating. The infamous inventor of the Sicilian bull, an instrument of torture in which the enemies of the regime were slowly roasted to death, certainly provokes a slight shudder, even with such an insignificant building.

The Museum of Akragas. Photo: KW.

The museum crammed with Greek pottery doesn’t need such special effects. Even if you’d take out all the average objects, the show cases would still hold enough highlights to make visitors stop and stare. (In this case, the average visitor would also realise for the first time what the highlights actually are.)

The oldest depiction of Sicily as triskelion. Photo: KW.

For instance this simple platter, which is, after all, nothing less than the oldest depiction of the island of Sicily in the form of a triskelion.

Golden hair net. Photo: KW.

This delightful golden hair net, which must have once decorated a lady’s head in Akragas, proves that the wonderful hairstyles such as they are found on coins depicting the Arethusa of Syracuse are no fantasy.

A hoard of aes grave. Photo: KW.

Highly relevant for the history of money is this hoard of aes rude, excavated in the sanctuary of Demeter in the 1960s hinting to connections with the neighbouring Italian mainland.

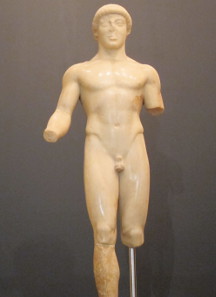

Ephebe of Agrigent. Photo: KW.

Pride of the museum is the Ephebe of Agrigent, created between 480 and 470 BC. …

Detail on a Roman child’s coffin from the 2nd century AD. Photo: KW.

… and a Roman child’s coffin that portrays moving scenes from the life of the deceased. In this caption, the bemoaned lost child is depicted in a Roman version of a go-kart.

The Gela Krater. Photo: KW.

Not to forget, the Gela Krater by the Niobid Painter.

One of the Giants which originally adorned the Temple of Zeus at Olympia. Photo: KW.

Another treasure we literally stumbled upon while looking for something different entirely. After breakfast we needed to go and inspect the plumbing. And – as ever so often – numismatics was right next to the toilets. You could only see the sign-board when descending from the museum’s exhibition rooms to the toilets downstairs. And now, guess what. Right. The numismatic section was closed.

Sign-board pointing to the coin exhibition. Photo: KW.

So I turned to the museum staff. Who were not spread out evenly around the museum, but tend to cluster round the entrance, deeply engaged in conversation. With the brightest of smiles I made my wish known. Serious pondering followed, accompanied by slowly shaken heads. Not that easy, not that easy, after all, yesterday had been Easter Monday. All of the rooms had been accessible then. Now some were tired and others not here at all. So they’d had to close the numismatic section. I repeat my charming smile, shower them with compliments about the museum, rave about the beauty of Sicilian coins … Finally my strategy of appealing to the staff’s pride worked. One of the women went off to get the keys and soon after we found ourselves in the numismatic sanctuary.

The collection. Photo: KW.

Don’t underestimate this. Akragas possesses an impressive collection, which has even been published in a Sylloge in 1999.

Two coins from the gold hoard in Agrigento. Photo: KW.

Then there are the 52 Republican gold coins from the 1987 Agrigento hoard find: 60, 40 and 20 as pieces, whose role in the debate about the introduction of the denarius should not be neglected.

Sir Alexander Hardcastle’s Villa Aurea. Photo: KW.

When we left the museum to continue to the Valley of the Temples, we began to feel the first signs of fatigue. The Valley has been a tourist sensation for centuries, not least thanks to Sir Alexander Hardcastle (1872-1933). By the way, this English captain, who settled in Akragas for his retirement, had German origins. He was a grandson to the famous German astronomer Wilhelm Herschel. Hardcastle used his own means to finance the first excavations and accommodated popular travellers, such as Goethe, in his Villa Aurea, located right next to the temples.

Akragas. Tetradrachm, ca. 471-430. From Gorny & Mosch auction sale 211 (2013), 48.

Akragas was founded around 582 by settlers from Gela and Rhodes. It is likely that at this point in time, Gela already had a trading base in the area that was now expanded into a proper city. Only years later, Phalaris, whom we’ve mentioned before, succeeded in gaining rule over the city. His name was a synonym for cruelty in ancient times. There is no clear evidence of the way he died, but there are a number of myths which speak of a civil uprising. Whether the stories are fact or fiction, we’ll never know after all these centuries.

Theron of Akragas, another tyrant we know by name, made Akragas the second important city of Sicily. His conquest of Himera led to the eponymous battle against the Carthaginians in 480 BC. After Theron had driven out the tyrant of Himera, the latter asked Carthage for help. Now the Carthaginians came facing Theron and his son-in-law Gelon of Syracuse. The Greeks were victorious and the spoils of war considerably increased the wealth of Akragas.

Akragas. Trias, around 450. From Gorny & Mosch auction sale 204 (2012), 1091.

The victory marked the beginning of the city’s heyday. In 472 Akragas became a democracy. Some of the most famous temples were built at this time and the city even produced a well-known philosopher, the poet Empedocles. Today his name is remembered primarily in connection with the tale that he committed suicide by diving into Mount Etna, a myth which certainly does not reflect a historical truth.

Akragas. Tetradrachm, 411 BC. From Künker auction sale 248 (2014), 7050.

From the year 430 onwards, when Timoleon of Syracuse successfully drove back the Carthaginians, the Corinthian general attempted to secure the west of Sicily by turning Akragas into a well-functioning city again. His plan worked out and by the early 3rd century Akragas was once more powerful enough that its tyrant Phintias was able to conquer and destroy the neighbouring Gela.

Akragas. Phintias, 287-279. From Gorny & Mosch auction sale 216 (2013), 2130.

From the year 430 onwards, when Timoleon of Syracuse successfully drove back the Carthaginians, the Corinthian general attempted to secure the west of Sicily by turning Akragas into a well-functioning city again. His plan worked out and by the early 3rd century Akragas was once more powerful enough that its tyrant Phintias was able to conquer and destroy the neighbouring Gela.

Akragas. Half shekel, 213-210. From Künker auction sale 158 (2009), 86.

The Second Punic War ended Akragas’s independence once and for all. The city was occupied by Carthaginians when the Romans fell in in 210 BC. The Romans called it Agrigentum and declared it a tributary civitas. Thanks to its ancient legacy, the city became Gergent (= place of the giants) in the Middle Ages, a name it retained until 1927 on maps of Sicily. Then along came Mussolini and renamed a number of cities with reference to their fascist legacy, after their famous ruins. This renaming unfolded in the same political context as the redevelopment of the Via dei Fori Imperiali.

Valley of the Temples, oil painting by Jacob Philipp Hackert (1737-1807). Source: Wikipedia.

Already for the affluent European travellers of the 18th and 19th century, the Valley of the Temples constituted a must-see. And it’s stayed that way. Akragas is an essential item on every travellers’ agenda. On top of that, Akragas has to suffer the cruise liners anchoring in Porto Empedocle that unload enormous crowds of tourists eager to see the Valley of the Temples. Imagining a peaceful walk among the ruins remains an imagination, even in the off-season.

Concordia Temple. Photo: KW.

Most well-known temple of the area is the Concordia Temple, which received its name rather arbitrarily from an inscription found nearby. Its construction is dated roughly between 440 and 430 and it is counted among the best preserved ancient temples due to its conversion into a church in 597.

Concordia Temple: façade and a glimpse of the interior. Photo: KW.

When tourism became an increasingly important economic factor, the church was done away with and the building restored to its original state in 1748.

A cent for each picture taken from this perspective and I’d be a rich woman within a year. Photo: KW.

Literally everyone who visits Akragas takes a picture from this particular perspective. Friends or fellow travellers posing in front of the statue are optional. A similar lack of creativity is displayed in the poses people assume. Those with a sense of decency touch Icarus’s cheek. Others his other parts. Oh well.

Temple of Iuno Lacinia. Photo: KW.

Whether the Temple of Juno Lacinia was ever really dedicated to this goddess is another question open to debate. It was erected between 460 and 450 and conveniently included a sacrificial altar in front of the entrance, which today serves as a place where tourists can rest their tired feet. We were no exception.

Temple of Heracles. Photo: KW.

Exiting you come across the Temple of Heracles, the largest and oldest temple of the cluster. It was built in the early 5th century and, in this case, it is actually not that unlikely that the temple was in fact dedicated to Heracles. At least we know that a temple of the same name and geographical location was mentioned in Cicero’s “In Verrem”. More precisely, Cicero accuses Verres of wanting to take possession of the temple’s huge bronze statue under some flimsy pretence.

The Olympieion. Photo: KW.

But don’t think you’ve seen it all yet! Just opposite, there is another archaeological site with the Temple of Olympian Zeus. It must have been gigantic. Maybe someone was trying to establish the place as religious centre. Next to the temple complex, remnants of sports facilities have been excavated that put even Olympia to shame once. (Perhaps one of Sepp Blatter’s ancestors was on the committee overseeing the construction, what do you think?)

Almonds. Photo: KW.

Once I realised I was taking more pictures of flowers and trees than of stones, we decided that enough was enough, at least for the day.

We repeated our visit to the excellent pizzeria, enjoyed a delicious late afternoon meal and returned to the hotel to tackle the project “next accommodation”. Not that easy. Our destination was Syracuse, but we had overlooked an Italian bank holiday.

Our plan would have failed dismally, had it not been for our lovely hotelier. We’d asked him for help with the phone numbers, whose logic surpassed the boundaries of my rational mind. All of my attempted calls came to nothing and I didn’t seem capable of getting a connection. He noticed my difficulties and took matters into his own hands, dialled and even enquired after potential accommodations himself. This is how we got ourselves a room at the idyllic sounding “Villa dei Papiri”. But more about that in our next episode, when we explore Sicily’s most famous ancient city: Syracuse.

And here you can find all episodes of “Sicily in full bloom”.