von Ursula Kampmann

translated by Teresa Teklic

June 26, 2014 – Easter Sunday in Sicily. It’s a family day, a day where grandpa and grandma, uncle and aunt, kith and kin gather around the table for a lavish meal. And then there is the story of an ancient people said to sacrifice their firstborn children to the gods. We are going to trace its history on the island of Motya, finding, amongst others, a tophet, the place where such infantile victims were buried.

Easter Sunday, April 20, 2014

Our plan for today was an encounter with the Punics, in Motya. For the sake of variety, I had chosen a considerably shorter route across the mountains instead of the road we always took. All of them yellow roads because I don’t trust white roads in Sicily. Being used to the luxury of German highways, you cannot imagine just how bad roads can get elsewhere.

Sicilian road, marked yellow on the road map. Photo: KW.

But today’s road really took the biscuit, although calling that a “road” would be an insult to other roads. On some sections, the speed limit went down to 10 km/h due to potholes. Our path was a mogul slope, with almost meter-high drops. The flowers and herbs on the roadside took care of what little tarmac there remained, ripping it open as they grew their way towards the centre of the road.

We drove past remote villages, guarded by seriously looking men in dark suits (Easter Sunday!) who had taken their seats on the village’s benches to comment on each passing car. Flocks of ladies with voluminous hair-dos and not so voluminous bouquets of flowers led their neatly dressed up children and grandchildren through the streets, to the cemetery. It was like being in a mafia film.

We were relieved when we made it to the highway without breaking an axel. And it had only taken us about twice as long as it would have on our usual route. Oh well. In the end we found the quay from whence a boat would bring us to Motya.

The salterns of Trapani. Photo: KW.

Because the settlement is built entirely on an island. Apparently the Carthaginians were rather fond of securing their cities by putting an ocean between them and the mainland. Already the jetty where the motorboats take off lies in a more than idyllic landscape. It is situated in the midst of the salterns of Trapani, where, until today, salt is extracted from sea water.

The local climate with its low air humidity and high level of solar irridation make it an ideal location for salt production.

The piles of salt are covered with tiles. Photo: KW.

In the salt evaporation process, the salt water was first of all fed into one of the shallower ponds with help of an Archimedes’ screw, powered by a windmill. As soon as the water had reached a sufficiently high salt concentration, it was channelled into another, even shallower pond. This process was repeated several times until nothing but pure salt was left over. Extracting pure sea salt took around 30 to 50 days. The salt fields could only be worked during the rainless months, from June to September.

View of the island Motya. Photo: KW.

Every half hour a boat crosses over from the salterns to the island of Motya, which has been known as San Pantaleo since the 11th century. At the time, it was settled by the Basilians (not Brazilians!). This interesting order resided primarily in the previously Byzantine south of Italy and is known for their Catholic reorganisation of Greek Orthodox monasteries.

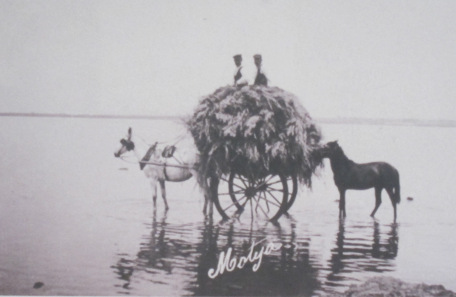

Photograph of a donkey cart on the waterway in the Whitaker Museum. Picture of the picture: KW.

Whereas it used to be possible to cross a flooded dam with merely getting wet feet, a boat is indispensable today.

Motya. Didrachm, around 425. From Künker auction sale 97 (2005), 241.

It is likely that Motya was founded as early as in the 8th century BC, roughly a century after Carthage. The settlers arriving to set up a trading bases didn’t come from Carthage, but from the Phoenician coast.

Motya. Tetradrachme, 415-397. Aus Auktion Gorny & Mosch 203 (2012), 49.

Historians have traced the name Motya back to the Carthaginian Mtw, a centre for spinning and wool trade. That would answer the question what the Phoenicians exported from Sicily.

Motya. Onkia, 413-397. From Gorny & Mosch auction sale196 (2011), 1192.

While the Greeks founded colony after colony, the Carthaginians focused more and more on Solus (or Soluntum), Panormus (now Palermo) and, of course, Motya.

Fortification Motya. Source: Selinous, Aldo Ferruggia / Wikipedia, CC BY-SA 3.0.

Although Motya developed into an important stronghold, we don’t know much about it until Dionysius I of Syracuse decided to conquer it. It took all the finesse of Greek siege machinery to bring the city down. Allegedly Dionysius even had his engineers develop a new machine, the catapult. When the city walls fell, the Carthaginians barricaded their houses so that the island had to be conquered house by house. Men, women and children who survived the bloodshed were executed by the Greeks afterwards.

Motya. Bronze, 415-397. From Künker auction sale 133 (2007), 7219.

A year later, in 397, the Carthaginians took their island back, but made no attempt at resettling it. The survivors left the place and with it their blood-stained memories behind and migrated to Lilybaion. Motya vanished from history.

Bird’s-eye view of Motya. Photo: KW.

Today, the island of Motya is private property. The main excavations were once initiated by a private citizen named Joseph Whitaker.

Joseph Whitaker, bust in the centre of Motya. Photo: KW.

He descended from a family that had made a fortune with the famous Marsala wine. And Whitaker was in good company. In October 1875, the Italian state had invited Heinrich Schliemann to confirm the popular 19th century assumption that the ancient Motya was located on the island of Pantaleo. But Schliemann left again after only four days. His damning verdict: “There is nothing to discover here and no historical riddle to be solved. I will not continue the excavations. Too much dust and dirt here … The islanders only speak their local idiom. Due to continuous intermarrying, everyone is related to everyone else on the island. These people are certainly the worst workers I have ever seen.”

Medal depicting William Henry Smyth. Source: Wikipedia.

The Italians had based their invitation to Schliemann on a report by one of the founding fathers of the Royal Numismatic Society. When marine officer William Henry Smyth had been stationed at the Sicilian coast during the Napoleonic Wars, he had formed an opinion on the location of Motya and published it.

It was Joseph Whitaker who proved the theory. He bought the entire island at once and ordered various excavations between 1906 and 1927, the results of which he published in 1921. The findings were clear: the ancient city of Motya had been located.

Motya remained Whitaker’s private property. His daughter finally bequeathed the entire land including all finds and excavation sites to the Italian state, shortly before her death in 1971. Run by a foundation, it is still state-owned. In other words, on Motya everyone pays for admission, even those above 65 or in possession of an ICOM pass.

The ephebe of Motya. Photo: KW.

To be fair, the island is worth the money for passage and entry. The round trip starts at the museum, whose highlight is a delicately worked kouros, discovered on the island in 1979. As Sicily doesn’t possess many large-scale sculptures from the antiquity, it is deemed a great surprise that such an excellent Greek statue from the 5th century BC was found just in a Phoenician colony. The robe is chiselled with such remarkable finesse that you can actually see the body underneath the slightly pleated, close-fitting cloth.

The hall exhibiting the tophet finds. Photo: KW.

But the tophet finds are at least as exciting. The word relates to a Hebrew expression which means “passage through the fire”. More than 1,000 small votive stele were laid open in Motya, which bear witness to the denizens’ sacrifices to their gods. Apart from animal bones, analyses of the unearthed skeletal remains also found human bones, mainly from babies and young children. They are witnesses to a tradition that has been recorded by Greek, Roman and Jewish authors: sacrificing that which is most precious to the human heart – your firstborn – to Baal. And please feel free to remember how Abraham was going to sacrifice his firstborn, Isaac, without turning a hair.

One of the tophet’s tomb steles. Photo: KW.

Not many tophets have been preserved. Six examples are known with certainty, one of them in Carthage, another one on the island of Sardinia. And of course that on Motya. Although the defenders of Carthaginian honour keep insisting that children sacrifices never existed. Neither did temple prostitution. Nothing but malicious slander of the unknown, the exotic. And who is to decide what’s true and what isn’t, with lack of evidence? The skeletal remains of a sacrificed baby do not look different compared to those of a young child that died of a natural cause. Perhaps today we are unable to understand that 2,500 years ago, a human life had a different value. And let’s not forget that the Romans too are known to have sacrificed human lives on the altar.

No other Romans and no children. But is the world really a better place because they killed a couple of young slaves instead?

I have to say, being in that hall really moved me. Naturally I had to see the place in the island’s northwest that used to be the tophet once, which is, by the way, clearly marked off by its location and the finds there as not belonging to the island’s cemetery.

A glimpse of the original Whitaker collection. Photo: KW.

A large hall in the museum, furnished with the original cabinets, bears testimony to Whitaker’s wide-ranging interests. They exhibit finds from Lilybaion as well as from Motya. One thing surprised me though: that there was no sign of any coins in the whole museum. But maybe there’s a logical explanation to that. Whitaker was friends with Victor Emmanuel III of Italy. Maybe he gave the excavated coins to the latter as a token of friendship …

Cothon. Photo: KW.

The excavation site stretches across a vast area of land. Plagued by oppressive temperatures and myriads of aggressive mosquitos, we first made our way to the excavation site’s highlight, the newly unearthed sanctuary at the cothon. Previously, the assumption had been this used to be a Phoenician inland harbour.

Recent map of the cothon sanctuary. Photo: KW.

Today it is believed more likely that in fact we are dealing with a large sanctuary, which also possessed a large water basin. The low walls surrounding the entire area are particularly impressive.

The south gate. Photo: KW.

Standing right in front of them, the south gate, once only a small part of the fortification that surrounded the entire island, comes into view.

“Cappiddazzu”. Photo: KW.

And another sanctuary has been identified, with the curious name “Cappiddazzu”. No, that’s not Phoenician, it’s Italian. As folk legend has it there’s the ghost of a monk from the ancient Basilian monastery guarding the local vineyards against thieves.

The necropolis of Motya. Photo: KW.

The necropolis of Motya was actively used between the end of the 8th century and the middle of the 6th century.

And the tophet. Photo: KW.

The tophet was apparently used as a sacrificial site for even longer. Thousands of votive stele have been unearthed here, each carrying the name of its donor and a phrase with his vow. Lab analyses have shown that next to animal bones also human bones were buried here, belonging to infants (0 to 6 years), but also to adolescents (6 to 17 years).

There would have been much more to see, but I was glad I made it back to the port at all. So we got back to the mainland in the late afternoon and took the opportunity that on this holiday dinner wouldn’t be served in the agriturismo to eat in a small restaurant with an excellent view of the salterns. It was worth it, even if just to watch the other parties, assembling several generations at one table to celebrate the holy Easter feast. There was the granddad handing out neatly wrapped 50 euro notes – 300 euros, all in all, if you multiply that by his six grandchildren. Adding the check for food and drink of some 15 people, Easter must have been a rather expensive undertaking for him this year.

The kitchens were very obviously unable to cope with all their guests’ wishes, especially if as extravagant as ours. As the restaurant had run out of fish, we’d settled on a plate of antipasti as first course and pasta respectively couscous (very common in this area) as main course. Only the two courses were served together instead of one after the other. To my friendly remark that I like to have my antipasti before the main course, the waiter replied with a disarming smile that today was Easter, after all, and there had been a little confusion in the kitchens. Well, honestly I don’t think he would have had the guts to confront one of his Italian guests with this “confusion”. On the other hand, I also didn’t want to be in the shoes of the inconspicuous elderly couple at the other table. They had waited an hour for their second course to be served after the first.

We had enough for the day and made our way back to the agriturismo. It would be our last night in the beautiful Balata di Baida. Our next adventure will lead us to Akragas and, together with thousands of other tourists, through the Valley of the Temples.

And here you can find all episodes of “Sicily in full bloom”.