by Ursula Kampmann

translated by Teresa Teklic

May 29, 2014 – The next stage of our trip around Sicily led us to the farthest north, to the region where the Carthaginians took up quarters. As a base camp we had chosen an agriturismo near Castellammare del Golfo, in the beautiful, until then unknown to me, village of Balata di Baida. When I had sent the email with our booking dates, I’d received a reply in flawless German …

Tuesday, April 15, 2014

In the (not too) early morning, we took off north on the highway. After all, Sicily isn’t too large. So we drove the close to 300 km from one end of the island to the other in our mini-Ferrari in a bit less than 4 hours. We didn’t stop. Too vivid was the memory of the Sixt staff warning us from the many car thefts in Sicily. And when we did stop, at one of the two motorway services this road had to offer, one of us always stayed behind to watch car and luggage. In hindsight probably a pretty unnecessary precaution. The warning had apparently just been a warning and designed to talk us into buying the expensive additional insurance.

Children playing in front of what looks like the setting of an Italian Western. Photo: KW.

Looking up the Italian Wikipedia entry for the district town Castellammare del Golfo is pretty shocking. There is a long article on the mafia and a quote from a renowned expert saying that Trapani and especially the area around Castellammare del Golfo are one of the mafia’s strongholds. Connections to the US were traditionally very close: many infamous Mafiosi from Castellammare had been actively involved in the US during the Prohibition and belonged to the gang around “Lucky” Luciano, Al Capone’s rival.

In real life, you barely notice any of this. What you do notice is Castellammare’s chaotic traffic and Balata di Baida’s remoteness. And right at the edge of the world, when you think there’s nowhere to go from here, lies the Agriturismo Camillo Finazzo, where we were going to spend the following nights.

View from the agriturismo’s terrace. Photo: KW.

The quietude of the abode was countered by the cheerful pragmatism of former Hanoveranian Annemarie Heine. Many years ago, love brought her to Sicily. Today she rules, just like a real Italian Mama, over a host of sons, daughters-in-law and grandchildren.

She welcomed us warmly, shooed away the dogs, who were almost jumping into our car for excitement, and showed us to our bungalow. With some pride she pointed out the relatively big window (not in the wall, in the door) that lets in enough light – a fairly unusual sight in Sicily. Sicilians don’t really get why you would want daylight in your room.

Our bungalow. Photo: KW.

That evening Annemarie cooked for us. The highlight was the long table with places for everyone joining the meal. This was not only great fun but also reminded me of the travel reports of the 19th century when travellers could choose between table d’hote and table separée. In the course of the shared meal animated conversations and discussions of travel plans sprung up. If you want to imagine this in greater detail, I can recommend the film adaptation of “A room with a view”. Annemarie silently dominated the scene from the head of the table without saying much. She seemed to take great joy in not having to go out into the world, but having the world come to her, to Balata di Baida.

Wednesday, April 16, 2014

Our first destination was Segesta, home to one of the most stunning temples on Sicily and not too far from Balata di Baida.

Segesta. Didrachm, c. 475/70-455/50. From Gorny & Mosch sale 190 (2010), 55.

Segesta lies beautifully embedded in a pretty hilly landscape. If we are to believe Vigil and his Aeneids, it was founded by a king named Acestes, son to the river-god Crinisus and the naiad Segesta. Silvia Hurter dedicated her last great monograph to the didrachms of Segesta. She accounts for the dog depicted on the obverse by reading him as a stand-in for the river-god Crinisus, a unique portrayal.

The “cirneco dell’Etna” – maybe an ancient dog breed? Photo: Wikipedia / Pleple2000. CC BY-SA 3.0.

She also comments on the possibility that the dog breed to which the depiction alludes may have survived on Sicily. Although, as she admits, such claims have to be considered with great care, as most European dog breeds were an outcome of breeding in the 19th century.

Segesta. Tetradrachm, end of the 5th c. From Gorny & Mosch sale 175 (2009), 41.

But let’s stick to the facts. Just like Eryx and Entella, Segesta was founded by the Elymi. We don’t know much about this people, only that they didn’t understand themselves as Greeks and that the Greeks thought the Elymi barbarians. Between Segesta and Selinus, which on today’s roads lie some 60 km apart, existed a long-lasting conflict. At issue was the border between the two territories and probably even more so the fact that Selinus barred the Segestans easy access to the sea.

Now, Selinus allied with Syracuse. And the Athenians thought that a welcome occasion to form an alliance with Segesta. When, in 416, a new war broke out between Selinus and Segesta, the Elymi turned to Athens for help. What followed is the famous story of how the Athenians travelled to Segesta to estimate the city’s wealth. It seems that they were tricked. Anyhow, they believed Segesta to be much richer than it actually was, invaded Sicily – and failed miserably. But we’re going to hear more about this in the quarry of Syracuse.

Segesta. Trias, end of the 5th c. From Gorny & Mosch sale 211 (2013), 73.

But the border dispute between Segesta and Selinus was far from settled. Segesta asked the Carthaginians for assistance, who then conquered the entire northwest of the island. Selinus was destroyed and so were Himera, Akragas and Gela. In return, Agathocles of Syracuse destroyed Segesta in 307. Even though Segesta was rebuilt afterwards, peace had finally come to Segesta and Selinus.

Segesta. Aes, after 262. From Künker sale 133 (2007), 7235.

Thanks to its role in the myth around the father of the Romans, Aeneas, Segesta was given special status in the Roman Empire. The city was free and immune, which meant tax exemption and the right to pass its own legislation. Even so, the situation did not develop very well. The location was simply less than ideal, too far away from the transport routes, and consequently Segesta became less important, to the advantage of Panormos and Lilybaion. Only when the Muslims were forced to withdraw to Sicily’s heartland during the Norman conquest it became a place of interest again. But in the second half of the 13th century, Segesta was utterly desolate.

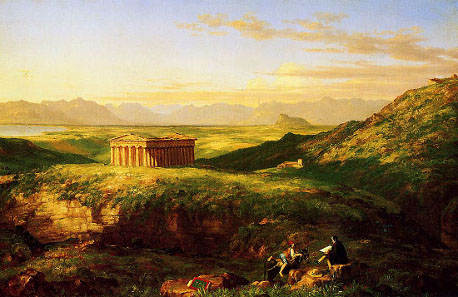

Temple of Segesta. Photo: KW.

This is the Segesta we are visiting today. We could already see the temple from the highway. Starting point to see the excavation is a big shop with a bar, which doesn’t sell admission tickets but at least the sought-after bus tickets which save you the 2-3 km uphill to the theatre. (Some people think they’re smart saving the 2 euros bus fare only to find out that perhaps they aren’t when the realisation hits them that the path is much steeper than they’ve anticipated …)

Temple of Segesta. Photo: KW.

It is a 10 minute walk from the bar to the temple of Segesta. We didn’t meet more than 3 tour groups and 50 or so individual visitors. Downright lonely, you could say. The temple is an extraordinarily well-preserved Doric exemplar, built some time in the late 5th century AD. I’ll desist from going into the number of columns and their measurements, these details tend to be forgotten after two minutes anyway.

Temple of Segesta. Photo: KW.

What is more interesting is that the construction was stopped halfway through. The temple lacks a cella as well as the fluting typical for this architectural style.

Thomas Cole, Temple of Segesta, in the foreground: artist at work. Painting from 1843.

Goethe, like uncountable other 19th century tourists, visited this temple. It was a must-see on the Grand Tour and is even said to have inspired neoclassicist architects.

The theatre of Segesta. Photo: KW.

The theatre – accessible by the aforementioned bus which leaves at the bar – was built for c. 3.000 spectators in the mid-3rd century BC.

Agora of Segesta. Photo: KW.

It lies in the centre of the little impressive excavation site of the ancient city, which has been explored by Italian archaeologists in the more recent past.

The oldest mosque on Sicily known to us. Photo: KW.

The building with a mihrab, a niche for prayer, probably presents the most interesting find and is commonly assumed to be the oldest mosque on Sicily. It tells the story of Islamic communities which, in the 12th century, during the heyday of the Norman rule, retreated to the more remote areas of the island to live their faith peacefully. They did this successfully until Frederick II came to power and aggressively moved against the Muslims in 1222. They are said to have mounted resistance until 1225. Perhaps, Muslims from here were among those who were forced to resettle in the Apulian Lucera.

We decided to walk back down instead of taking the bus and enjoyed the hike on the scenic trail, which again and again offered new views of the gorgeous temple of Segesta. We also gave friendly advice to all the poor souls who panted and sweated their way uphill, asking us how much further the bloody theatre was.

View of the richly decorated apse of the cathedral of Monreale. Photo: KW.

As the day was still young and we were still feeling adventurous, we drove straight from Segesta to Monreale, though by taking shortcuts and without even coming close to Palermo (and its traffic). A large parking lot is located immediately below the cathedral. It was more or less empty when we got there. And it didn’t take us long to find out why: it was siesta. The cathedral would only reopen in a good two hours.

“Madonna Lactans”, the Nursing Madonna, painting from the 14th c., formerly part of the cathedral of Monreale. Photo: KW.

We took the opportunity to have a look around the open museum. Yes, there was too much Baroque for my taste, but apart from that there were a few highly interesting objects.

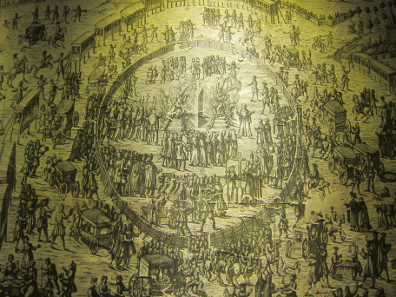

Francesco Cichè, Brother Romualdo and Sister Gertrude being burnt at the stake on April 6, 1724. Photo: KW.

For instance the pictorial representation of a Spanish autodafé that was held in Sicily in 1724.

Moneychanger at the autodafé. Photo: KW.

The moneychangers supplying the bystanders with change are clearly recognisable in the crowd.

Monetiere: Italian for “coin cabinet”. Photo: KW.

Not to forget this grand coin cabinet from the 17th century that used to belong to an aristocratic household in Palermo.

The cathedral’s cloister. Photo: KW.

But the magnificent cloister of Monreale, which, fortunately, has longer opening times than the cathedral, almost surpassed everything else. It once belonged to a Benedictine monastery and offers not only 228 columns with richly diverse ornaments, but also a multitude of capitals of astonishing beauty and storytelling capacity.

Capital in the cloister of Monreale. Photo: KW.

Here, one of the wise virgins expecting her bridegroom with enough extra oil for her lamp.

Capital in the cloister of Monreale. Photo: KW.

King William II presenting his newly built Cathedral to the Virgin Mary.

Capital in the cloister of Monreale. Photo: KW.

Constantine the Great and Helena holding the True Cross between them.

Capital in the cloister of Monreale. Photo: KW.

Cain slays Abel and is expelled.

And if I have sparked your curiosity, there is a webpage specifically dedicated to the cloister which allows you to view each individual capital!

Bronze gate by Bonanno Pisano. Photo: KW.

We got especially lucky that day: due to construction works, we were able to sneak into a usually closed off area, to the famous gate of the Cathedral of Monreale created by Bonnano Pisano. The poor fellow came to fame because the leaning tower of Pisa was considered his fault.

Noah’s Ark: detail from the bronze gate by Bonnano Pisano. Photo: KW.

What people tend to forget, unfortunately, is that this man pretty much single-handedly revolutionised bronze casting. He was the first to cast a gate which presented its depicted scenes in real relief.

While we were still admiring the fantastic gate, a guard approached us and instructed us explicitly (and not very politely) to get ourselves immediately (!) back into the main hall. That we did and found ourselves facing the more than 6,000 square metres of mosaic completed by Byzantine artisans in a minimum of time.

Mosaic in the cathedral interior: William II hands the cathedral over to the Virgin Mary. Photo: KW.

Even though this mosaic may look like a proof of heartfelt piety, William’s II reasons for erecting the Cathedral to the Virgin Mary were more than mundane. When William had been still underage, the council had instituted Walter Ophamil as Bishop of Palermo against the queen regent’s wishes. And Ophamil was eager to strengthen his position, which meant that William had a rival for power in his own residential city. To restrict the episcopal influence, he founded a new bishopric right next to the municipal border of Palermo and there instituted a bishop of his own choosing.

View of the cathedral’s interior. Photo: KW.

What makes Monreale famous is the extraordinary wealth of images flooding your senses. You get an idea of the great art that has been lost in all the other Romanesque and Byzantine churches.

Mosaic in the cathedral’s interior: Noah’s Ark. Photo: KW.

As usual, the illustrations relating to the Old Testament are more than vivid.

Sepulchre of William II. Photo: KW.

The magnificent edifice was originally planned as final resting place for the house. In the end, though, only the family of William II found their final peace here: his father, his mother and his brothers.

Sepulchre of Saint Louis. Photo: KW.

Someone else who found his peace in this church, at least in pieces and for a while, was Saint Louis. As you may know, he died in 1270 after his stupid crusade to Tunis and his corpse seemed to become a promising business opportunity on the relic market. Ergo people were fighting about it.

A compromise suggested seething the saint-to-be in wine and vinegar until the meat would fall off the bones and facilitate the dispensation. King Philipp III could take the bones to France and Charles of Anjou received the entrails for his kingdom in Sicily. Thus they ended up in Monreale until in 1860, on his flight from Garibaldi, Francis II took them along, first to Gaeta, then to Rome and finally to his exile in Bavaria. After Francis’s death, the relics changed hands again. Cardinal Charles Lavigerie, archbishop of Algiers, transferred what had been left over at this point to Carthage, Saint Louis’s place of death. At last, the relics found some rest between 1890 and 1956. However, when Tunisia declared its independence, France wanted its property back. So the relics were transferred back to France, where they still lie today, in Sainte-Chapelle, the same place where the bones had been kept until the French Revolution.

We too were tired from such extensive travelling. We returned to Balata di Baida to rave about Segesta and Monreale in the company of the many other guests.

In the new episode of the numismatic diary “Sicily in full bloom” we will visit the Venus temple in Eryx and the famous Good Friday procession in Trapani. Don’t miss it!

And here you can find all episodes of “Sicily in full bloom”.