by Ursula Kampmann

translated by Teresa Teklic

May 8, 2014 – Do you also start daydreaming when you think of Sicily’s fantastic coins? The Arethusa’s head, crab and eagle or the natural beauty of the celery leaf! We’re going to visit the cities where these coins originated. Accompany us on our journey through the paradise of each coin collector! Today we’re visiting the Roman Villa Casale and Morgantina. And to top things off, we discover a coin treasure.

Saturday, April 12, 2014

Finally! Finally we were going to Sicily. Finally we were on the plane together with 178 other tourists wanting to see the beautiful Italian island. Finally we took leave from German perfection and organisation.

A huge car to carry the luggage for three weeks. Photo: UK.

Our enthusiasm didn’t last very long though: as soon as we got to the Sixt counter we already missed the German perfection and organisation. The E-class mid-range car we had booked turned out to be a tiny Smart. Yes, absolutely certain, that was the pre-booked car (it wasn’t) and another one wasn’t available. Did we want it or not?

Well, we wanted to get to our accommodation. And we were successfully talked into buying an insurance (quote: Every second new Smart on this island gets stolen, and also, the insurance doesn’t even cover the Province Catania because too many cars are stolen here, so in case of theft you’ll have to pay anyway).

Attention! Sudden braking may cause decapitation by suitcase! Lucky enough we didn’t have to brake suddenly… Photo: KW.

A brief introduction to driving a semi-automatic car? Or maybe a manual – preferably in a language we understand? Totally overrated!

So we were stood in the parking lot, trying to decode the mysteries of a technology which did not reveal themselves to us. By the way, we weren’t the only ones. The shared desperation about not being able to move or even start their cars created a sense of solidarity among all the Northern Europeans in the parking lot. With combined efforts we solved the first mystery, how to open the trunk of a Smart (very bizarre – first you push up the rear window only, then you can push down the metal part of the car’s back). Hard to believe, but with just the right amount of physical violence directed at our luggage and extensive verbal abuse directed at the absent Sixt staff, our two bigger trolleys and the smaller hand luggage eventually fit into the vehicle (please, you really can’t blame us for having too much luggage, after all we expected a small mid-range car with an actual boot).

They call it a ‘clutch’ – operating it is anything but trivial. Photo: KW.

Oh, and if you think all you have to do to start a Smart is turn the keys – you’re wrong. A sophisticated technique of adjusting hand gear and pedal is necessary to start the car, reverse or even change gears (yes, you can do that!). A short explanation would have been extremely helpful. But as it was we practised our understanding of the car’s phenomenology and attempted to interpret the reactions to our behaviour in such a way that we would be able to produce the desired effects not just by pure coincidence in the future (by the way, it would take us almost four whole days to start the car on command).

Of course we took the wrong exit leaving the airport. But we did successfully locate the Masseria Pezza del Medico near Catania where we had booked a room for the first three nights on Agriturismo. The only obstacle in our way seemed to be a white gate. It was closed and wouldn’t move an inch.

At some point I had the clever idea to call the Masseria. After all I had the booking confirmation with all the names and addresses with me and there were three phone numbers at the entrance gate. The first number didn’t exist. The second was answered by the mail box. And the third by a grumpy man who had never in his life heard of a Masseria Pezza del Medico.

By this point I almost wished we’d been one of the many tourists waiting to be picked up by men and women with colourful signs saying “Club Méditerranée” or “Studiosus” at the airport. Well, there was only one thing left to do: walk.

Somewhere around here there had to be the farmhouse with the rooms we’d booked. Of course there was nothing whatsoever in sight. But, as they say: nothing ventured, nothing gained. So I started walking down the dusty road along orange plantations (in different circumstances, I would probably have found that pretty romantic) and after a good quarter of an hour I met a giant farm dog barking at me (the barking was meant as a friendly gesture, I was told later). A small but very upset woman welcomed me with reproaches. Why hadn’t I contacted her earlier? If she’d known, she would of course have been at the gate to let us in! Well, you always know better in hindsight.

So eventually we arrived. Our rooms were ready and we the only guests. Still our padrone insisted on cooking a delicious four-course dinner. We tried local olives and decided that we didn’t want to switch with the package tourists at the airport after all. Especially when padrone Eugenio joined our company. His wife Marisa is from Malta and her English impeccable. Eugenio’s isn’t. But thanks to plenty of wine my rudimentary Italian was sufficient to start a lively conversation.

Eugenio proudly told us how he bakes his own bread and that the olives he served us came from his own trees. We told him where we came from and why we were here. And then someone mentioned the word “numismatici” – and Eugenio said that he was still in possession of a box of coins inherited from his great-grandmother, who had lived near Caltanisetta. The coins had been discovered when working on the fields. Of course we were curious – and it was agreed that we would take a look at the contents of this legendary box after dinner the next day.

Sunday, April 13, 2014

Although curious about the coins, we would have to wait until the evening to satisfy our curiosity. After all we were her to explore the region. The weather was fantastic, sunny with little clouds without being too hot. We decided to visit the highlight of our trip right away, the Villa Casale in Piazza Armerina. Despite of several previous trips to Sicily we had never seen this attraction (World Heritage Site since 1997) before because its location is so difficult to access using public transport that it requires considerable efforts. Unfortunately, we had only ever travelled with public transport before…

We drove upcountry, towards Enna. The streets were in a remarkable state. I haven’t seen that many pot holes in a very long time – and we’ve seen many really bad roads in Europe and in Turkey, believe me! No wonder nobody dares to charge tolls for this miserable highway.

Floor plan of the Villa Casale. Photo: KW.

On our arrival at the Villa Casale in the late morning, a huge, empty parking lot was awaiting us. One, maybe two busses were parked there and perhaps 30 private cars. But the size of the parking lot was an unmistakable indicator of the enormous masses of visitors which must come here during the main season…

The ovens heating the Villa’s private baths. Photo: KW.

And the excavation is without doubt worth the visit. 45 of the rooms of the former Roman villa have been preserved and are ready for public viewing, most of them decorated with fantastic mosaics. The villa was built in late antiquity, presumably in the early 4th century. This was the heyday of Sicilian rural life. Sicily’s corn fields made the island rich – or rather, the corn field owners. While previously the aristocracy would have lived in the larger cities, the nobles preferred the spacious luxury and comfortable life at their country estates during the time of the Tetrarchy. The Villa Casale isn’t the only proof of that. Several, even larger, buildings from this epoch still exist in Sicily, even if they aren’t as well preserved.

Slave carrying water. Mosaic from the thermal baths. Photo: KW.

Scholars disagree on who once built the villa. Some really like the idea that it belonged to Emperor Maximianus Herculius or at least his son Maxentius. However, the fact that several other, partly larger, estates existed on Sicily at the time speaks against this theory. And considering that Diocletian’s retirement home, where he cultivated his famous cabbage, encompassed 30,000 square metres renders the hypothesis of the imperial summer cottage even more unlikely.

The former owner of the villa? Detail from the mosaic in the great hallway. Photo: KW.

It seems more likely that the luxurious mansion belonged to a private person. Perhaps it really was Lucius Aradius Valerius Proculus Populonius, governor of Sicily between 327 and 331. He had been the organiser of the infamous games in 320 in Rome, about which people would still be talking for years. The fact that the circus and the hunt are central themes in the villa’s mosaic speaks in favour of this hypothesis. (On the other hand, he wasn’t the only aristocrat who liked hunting and the circus…)

The frigidarium in the thermal baths. Photo: KW.

We entered the architectural complex through the thermal baths and were in love with it the moment we saw the first mosaic. Sea monsters and fishing Erotes decorated the floor of the frigidarium. Immediately the camera was drawn and the mosaic recorded from every imaginable angle possible. Until we turned around the next corner and realised that there were even grander mosaics still to come. Of course we took a myriad of pictures of this mosaic too. (You can see where this is going.) Only to realise that the next room was even more breathtaking, and so on. Honestly, the Villa Casale alone is worth a trip to Sicily.

The room of the two apses, depicting a chariot race in the Roman Circus Maximus. Photo: KW.

At this point, we are going to skip most of the 300 pictures we took that morning and present you with a selection of the most stunning mosaics and, respectively, with those most interesting to us numismatists. For instance this chariot race in the Roman Circus Maximus, …

Traian. Sestertius, 103-111. Rv. Circus Maximus. From auction sale Numismatik Lanz 144 (2008), 475.

… which has also been depicted in a similar manner on this coin.

The Little Hunt. Photo: KW.

The “Little Hunt” mosaic in the (winter) dining room is a unique example of elaborate beauty and attention to detail.

Boar hunting. Detail from the ‘Little Hunt’ mosaic. Photo: KW.

This excerpt shows a boar hunting. The hunter visibly carries a boar spear, whose construction prevents the spearhead from penetrating the animal’s body too deep for removal of the spear.

Rest. Detail from the ‘Little Hunt’ mosaic. Photo: KW.

In the centre of the mosaic hunters are roasting a bird to eat it in the cool shade of a canopy mounted in the trees. The horses are tethered. The net for the stag-hunting is fastened to the tree’s crown. And just like today, the participants of the picnic drink an awful lot as long as the bird is still roasting over the fire.

Detail from the mosaic in the hallway of the great hunt. Photo: KW.

The mosaic in the hallway of the great hunt also answers certain questions of numismatic interest. Numerous coins depict animals being slaughtered in the circus. But have you ever thought about how the beasts got to the capital from all those different countries?

Philippus I. Antoninian, 248. Rv. Mahout riding elephant in a circus. From auction sale Künker 204 (2012), 798.

For instance, how did you get a heavy elephant across a shaking bridge into the bilge of a cargo ship?

Detail from the mosaic in the hallway of the great hunt: elephant. Photo: KW.

Here’s how: you put it into a net and lead it across by pulling on heavy chains tied to its tusks.

L. Livineius Regulus. Denar, 42 BC. Rv. Bull at the games in Caesar’s honour. From auction sale Gorny & Mosch 195 (2011), 372.

And what about this raging bull?

Detail from the mosaic in the hallway of the great hunt: bull. Photo: KW.

Easy! You just stick a slat on his horns before it can stick anything (or anyone) else on them and pull!

Caracalla. Denar, 206. Rv. Circus scene. To the left, an ostrich. From auction sale Numismatik Lanz 125 (2005), 863.

This reverse, issued for the Secular Games of 204, shows that even ostriches made an appearance in the Roman circus.

Excerpt from the mosaic in the hallway of the great hunt: ostrich. Photo: KW.

And this is how the birds travelled to Rome.

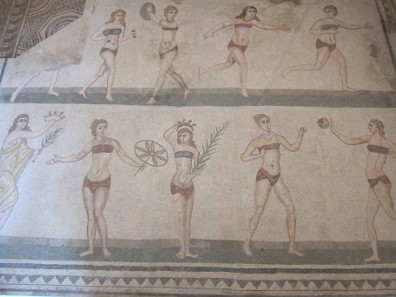

The ‘bikini girls’ mosaic. Photo: KW.

The depiction of the “bikini girls” is probably even more famous, although nowadays I guess these young ladies would have to consult a plastic surgeon first before launching a career in Italian television.

By the way, at a closer look you can see clearly that in this room another, older mosaic with geometrical patterns lies below the actual mosaic.

As much as there is to tell, here are only two more pictures with numismatic references:

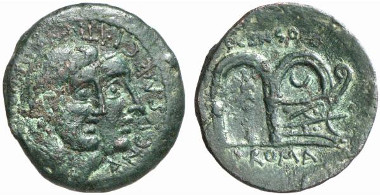

C. Marcius Censorinus. As, 88. Rv. Two ship houses, one of them with ship. From auction sale Künker 124 (2007), 8306.

There’s the As of Caius Marcius Censorinus. On the coin he prides himself with his ancestor Ancus Marcius, who, together with his (fictitious) grandfather Numa Pompilius, adorns the coin’s obverse. According to tradition it was that Ancus Marcius who had the first ship houses built in the harbour of Ostia.

Mosaic in one of the Perystile’s arcades. Photo: KW.

Such ship houses form the background of this picture of fishing Erotes.

Table with prize crowns, below bags containing prize money. Photo: KW.

Or this table covered with prize crowns.

Odessos (Moesia Inferior). Gordianus III. AE. Rv. Prize crown. From summer sale Rauch, September 18, 2013, 823.

We have seen those prize crowns on numerous coins from the Roman provinces.

Detail showing the bags containing prize money. Photo: KW.

The two moneybags below the table, on the other hand, are rather an unusual sight on coins…

Pergamon (Mysia). Elagabal. AE. Rv. Prize table, below two purses. From Auktion Gorny & Mosch 195 (2011), 332.

…which doesn’t mean they don’t exist.

Detail from 27.

For instance on this coin from Pergamon, which depicts them unobtrusively below the table, just like in the mosaic.

You might think that we’d seen more than enough for one day by this point. But after some refreshments we were on our way to the nearby excavation site of Morgantina – this may ring a bell with some of you who remember it from the book title “Morgantina Studies II. The Coins”.

Morgantina. AE, around 200 BC. Rv. To the right: soldier. Below, the inscription HISPANORVM. From auction sale Gorny & Mosch 164 (2008), 55.

If you do, you’ll remember that the ancient settlement was identified with the help of coin finds. The renowned Turkish archaeologist Kenan Erim, who excavated Aphrodisias, thought there was a connection between a large concentration of coins all inscribed HISPANORVM and a passage from Pliny. The report talks about the conquest of Morgantina by the Romans who then gave the city to a group of Spanish mercenaries.

Morgantina. Litra, c. 465 BC. From auction sale Gorny & Mosch 142 (2005), 1146.

The earliest historical evidence which mentions Morgantina comes from Diodorus Siculus who reports that Ducetios, leader of the local Sicels, took Morgantina when he established his own rule in the year 459. His realm fell apart. Could be that Morgantina became independent again or that Syracuse brought it under its rule. However that may have been, Syracuse surrendered the city to Kamarina during a war in 424.

Morgantina. Tetradrachm, around 340 BC. From auction sale Gorny & Mosch 199 (2011), 75.

But already in 396 Morgantina was reclaimed by Dionysius of Syracuse. The Syracusani held sway over the city until the Second Punic War when the Romans took it and, as mentioned above, handed it over to the Spanish mercenaries.

Morgantina. Eunos, 135-132. Stater. From auction sale Gorny & Mosch 207 (2012), 61.

This unique gold coin bears witness to another episode in the history of Morgantina, the slave uprising led by Eunos. Born a free man in Apameia in Syria, Eunos became famous as a charismatic soothsayer and miracle worker and surrounded himself with a large group of followers. When his vision of a successful invasion of Enna by slaves came true, he was crowned King Antiochos by his followers. Calpurnius L. Frigo and Publius Rupilius finally put down his rebellion and massacred 8,000 rebels in Morgantina and another 20,000 in Enna and Taormina. The inscription on the reverse, Philippos, refers to the Macedonian king and was meant to invest the coins with more authority.

The city is last mentioned by Strabo, who remarks that Morgantina didn’t exist anymore in his lifetime, i.e. in the 1st century AD.

The excavation site of Morgantina. Photo: KW.

From the lofty vantage point you can get an excellent view of the structure of the Roman macellum. A macellum was a Roman market place, usually selling meat, fish, vegetables and delicacies. The buildings resembled each other across the Roman Empire and are understood by archaeologists today as an important criterion to discern the degree of Romanisation of the city in question.

You can easily make out the contours of the central building in the middle, featuring a well or water fountain, while the shops were clustered around a small courtyard.

The macellum. Photo: KW.

From the lofty vantage point you can get an excellent view of the structure of the Roman macellum. A macellum was a Roman market place, usually selling meat, fish, vegetables and delicacies. The buildings resembled each other across the Roman Empire and are understood by archaeologists today as an important criterion to discern the degree of Romanisation of the city in question.

You can easily make out the contours of the central building in the middle, featuring a well or water fountain, while the shops were clustered around a small courtyard.

Nero. Dupondius, 64. Rv. The Macellum Magnum. From auction sale Gorny & Mosch 211 (2013), 577.

Only one Roman supermarket ever came to numismatic fame: the Macellum Magnum, a large, roofed and domed building, formerly located where the Christian church Santo Stefano Rotondo stands today.

The mint of Morgantina. Photo: KW.

Oh, by the way, apparently a mint has also been discovered in Morgantina. Still we decided not to walk down to the ruins as it was getting late and because we wanted to get back to our Agriturismo and inspect the box of coins we’d been promised!

May I introduce you: the lady who collected the coin finds many decades ago near Caltanissetta. Photo: KW.

Eugenio held his promise and promptly approached us with the box as soon as we had eaten our dinner. Wrapped in several smaller bags, the coins came in a box of maybe 25 x 20 x 50 cm. Eugenio’s great-grandmother is said to have collected the coins more than a century ago on her family’s land bear Caltanissetta.

Well, for some of the coins this surely wasn’t true. They were leaden counterfeits (and pretty bad ones too): some of them very creatively decorated medallions of some 8 cm diameter, some imitations of the most common type of Sicilian tetradrachms and yet some of the famous en face portraits of Catane.

However, a great part of them were real coins: several Hellenistic bronze coins, for instance two neat pieces from Himera, one with the Gorgoneion, one with a rooster. Besides the old lady had assembled a heap of Roman sesterces (no, not of a quality that would be interesting for collectors) and even more late Roman coins. A few Byzantine coins and even fewer Islamic and Norman pieces were also among the collection. The Spanish period (15th century and later) was represented in high numbers again. To our surprise there were also numerous coins from Malta.

Then again, the 19th century coins were presumably inherited rather than found. The family had also preserved a whole bunch of coins from the time of the fascist regime.

Our hosts greeted the whole thing with enthusiasm and announced that they were going to exhibit the coins in a glass cabinet in their public room.

And that was only the first day of our adventurous trip to Sicily! Stay with us when we visit Taormina next week and get excited about the city where the International Numismatic Congress in 2015 will take place!

And here you can find all episodes of “Sicily in full bloom”.