by Björn Schöpe

May 14, 2013 – The MintWorld staff has its office in Germany near the Swiss border. And it takes only 10 minutes by train to reach the next town, Steinen, in the green Wiesental, the ‘Meadow Valley’. There the company H2O has its headquarter. Actually, for the first time we met during the World Money Fair in Berlin. And we said immediately: ‘That sounds intriguing what these guys do, we really must take a closer look.’ And here you can read a report of our visit at H2O.

The company with the chemical name for water is specialised in minimising the consumption of this elementary resource. And companies from nearly all fields benefit from this service as a look into the showcase placed in the entrance proves: there you can find numerous references from Rolex to Canon, and from Audi to Bosch. H2O can be of interest for nearly every firm that uses water during their production process. In the showcase, though, there are no coins although today many important mints are satisfied customers of H2O like the Berlin Mint, the Mints of Baden-Württemberg, the Mints of India, Monnaie de Paris, Mint of Finland, former Saxonia, just to cite some of them … All these companies benefit from the goal H2O aims at: the liquid discharge production. What is that, anyway? Dipl.-Ing. Jochen Freund, H2O’s Product and Business Development Manager explains it to us on the spot.

H2O headquarter in Steinen.

The company was founded in 1999, in 2005 they moved to the new headquarter. However, this building is already getting too small for the business and the neighbouring area has been purchased. A new building is currently being projected. Indeed the mid-size business H2O has continuously grown. While the company’s volume in the first year amounted to 2 million euros, today it is of 14 million. Now some 90 people are employed at H2O and the company has a worldwide net of subsidiaries and sales offices. Basically H2O deals with how we treat the natural resource water.

Wastewater.

The water consumption in the industry is gigantic. To produce one ton of steel some 18 cubic metres of water are required, for a laptop a bit less is needed (15 cubic metres), the production of a car consumes even 400 cubic metres. After the production the water is being processed and cleaned as possible in order to dispose it into the sewer system. However, the water is still impure and not good enough for recycling; additionally the industry faces high costs since wastewater cost is much higher than the cost of fresh water.

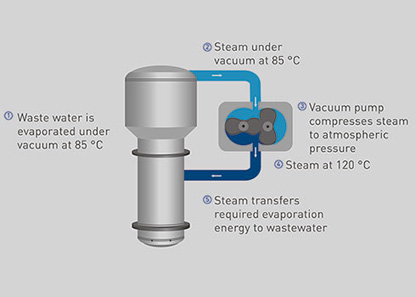

This scheme shows how Vacudest operates.

At this point Vacudest enters the scene, H2O’s product. Invented as far back as the 1980s the principle of vacuum distillation has been continuously improved since. Today it is employed even in large factories. The scheme shows how this machine operates. The industrial wastewater is evaporated under a vacuum at a temperature of ca. 85 degree Celsius. The steam is attracted by a vapor compressor and there, at normal pressure, heated up again. The energy which is produced during that operation serves for evaporating the wastewater. So, at the end of the process remains pure water on one side that is inserted into the production cycle (mints will appreciate particularly that the process water is free of hardness and thus more suitable for high quality blank production than fresh water); on the other side remains the impurification substance that sedimented and can be accordingly treated or recycled. No energy is required except for the vapor compressor, hence the running costs are low; often, Mr Freund explains, the acquisition costs have already amortised after two years. The company produces no more wastewater at all, the pure process water remains in the production cycle.

Vacudest.

These Vacudest wastewater treatment systems are produced in Steinen, however, this fact alone would not have made the company what it is today. When walking in the building you see immediately what H2O does in addition.

Before an evaporator is being produced it is necessary to know what kind of wastewater it will have to deal with. The demands are totally different between purifying wastewater from the coin producing industry or from the printing or cosmetics industry (indeed this system has been adopted in these industry branches too!).

In the H2O laboratory chemists analyse what the Vacudest will have to purify at the future customer’s company.

Therefore the potential customer sends a representative trial of their process water to H2O, where it will be analysed in the proper laboratory. Hundreds of such trias are stored at Steinen.

As for mints H2O only needs to know what coins are being produced in the facility (euro circulation coins, silver coins …). The chemists can refer to sufficient referential trials from other mints in order to determine the composition of the expected wastewater. Then the machine is calibrated according to the customer’s demands. Nevertheless the Vacudest may later be modified if required.

A view of the production hall at H2O where Vacudest machines in various sizes and production phases stand side by side.

The production hall is full of Vacudest machines in various production phases and sizes hence liquid capacities. The smallest model (XS) may purify up to 360 cubic metres per year while the XL edition can face up to 12,000 cubic metres of water per year.

Mr Freund underlines what limits the firm: it is not the potential demand but the shortage of skilled employees. Being so near to Switzerland it is difficult to find young, highly trained specialists who settle for a German salary. But H2O need highly skilled employees, hence they train them themselves. Currently 16 apprentices work at H2O – that makes 20 percent of the whole staff. Obviously H2O knows how to attract new employees.

Training programmes are a central aspect in H2O’s customer care.

In a room beside the large production hall you can see an open Vacudest. It makes clear a central point in H2O’s way of operating since this is a demonstration pattern which can even be rent but, which is over all used for training purposes. Indeed these machines must be used and maintained by trained personal. H2O trains the maintenance operators. After they worked with the machines for a couple of weeks and, hence, know where they may experience problems, H2O offers them an additional training seminar in their Steinen headquarter. At this point the operators know what to ask about the Vacudest. H2O ingeneers implement some errors and breakdowns into this demonstration pattern to give the trainees some challenge. There is most certainly no better way of training!

If the customer wishes technicians can access any Vacudest worldwide via internet from the headquarter.

You see it anywhere that the customer is at the centre of H2O’s activities. The Vacudest is geared to the needs of the customer. But on the first floor of the building, in the office, the customers are ever-present too: phone calls, e-mails, technicians who can access with their computer any Vacudest worldwide for maintenance purposes and help with problems, just in case problems should come up. As experience has shown the machines need regular maintenance and care but even under rough conditions dealing with aggressively inquinated water they operate reliably for many years.

Considering environmental issues H2O has the finger on the pulse. But the major argument why their machines sell so well are the financial savings, as Mr Freund states.

Thus we terminate a very instructive morning and say thank you to Jochen Freund and H2O for giving us that insight into a company which will certainly in future become a well known name in the coin world too.

If you want to learn more about the company and the technical details into which we did not delve here, be sure to visit the H2O website.