translated by Annika Backe

The year is 1874. Once again, the representatives of the members of the Latin Monetary Union gather for a crisis meeting. As a matter of fact, the currency is in danger. In the previous years, silver has experienced an incredible slump in prices. And now all countries are minting far too many silver 5 franc pieces because they generate the largest seigniorage. The gold coins, in contrast, which are much more expensive in comparison, disappear from circulation.

France loves to hold Germany responsible for this currency turmoil. Gullible Fritz was to blame, who, following the model of the British, had switched to the gold standard in 1871. Tons of German silver money would now be melted down and thus depress the London Fixing.

Well, a small amount of German silver may well have flowed to London, but the real masses actually came from the New World, where industrial methods made it possible to yield much more silver than could ever be absorbed by the market.

View from one of the cemeteries to Virginia City, or rather what is left of it. Emerging from the hill, the silver ore runs underneath the city, right to the houses in the valley. Photograph: UK.

In Virginia City, the Silver City, for example, up to 25,000 people were busy exploiting the bonanzas – as the silver deposits that were part of the Comstock Lode were called.

Ore with high silver content from the Consolidated Virginia Mine, which, between 1873 and 1880, yielded gold in the then value of $105 million. Photograph: UK.

In the 20 years between 1860 und 1880, they mined 6,971,641 tons of pure silver. To transport this amount of silver today, it would take a freight train stretching from Madrid to Moscow.

A look at today’s Main Street of Virginia City with its many saloons and souvenir shops. In the 1870s, this used to be a major city that had its own opera house. Photograph: UK.

Today, there is only little that could tell of the former world-historical significance of Virginia City. The city is a minor tourist attraction. There is a small train, with which you can drive through the very steep site, and a Western theater where gunmen are shooting at each other twice a day.

Yes, these are actually wild mustangs, even if they do not look different from normal horses. Photograph: UK.

Wild mustangs are grazing in front of the hotel, and that feels quite right for everyone who has watched Bonanza in his childhood days. After all, the Cartwright TV-farm was located not that far away from Virginia City, a day’s ride southwest towards Lake Tahoe. (By the way, Virginia City was marked on the very map that is being burnt in the opening of Bonanza.)

Marshall Mint, where the official assayer office used to be. Photograph: UK.

In the Marshall Mint, where people buy bullion coins and jewelry nowadays, during the silver boom, the office of the official assayer of precious metal was located, …

“Indications? Sure!” From J. Ross Browne, A Peep at Washoe, published in 1861.

… who checked and determined the silver’s value.

Ponderosa Saloon, the former Bank of California. Photograph: UK.

The entire subsoil of Virginia City is riddled with tunnels and shafts. And it gives you to a strange feeling once you realize that you may descend …

From the Ponderosa Saloon, you may enter into the first shafts of a mine. Photograph: UK.

… from the Ponderosa Saloon, where the Bank of California used to be located, into the underworld.

Visit to the underworld. Photograph: UK.

You do not get very far, though. 300 meters at the most, this is how far you can get into the hill. The biggest attraction is the accompanying guide switching off the electric light when he wants to show that a candle is enough to illuminate the darkness inside the mine.

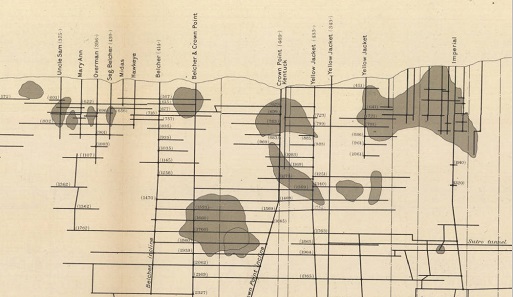

The network of tunnels running underneath the city. Photograph: UK.

In what is modern Virginia City, it is hard to imagine the incredibly innovative and technically modern way in which the vast deposits of silver were being exploited in the past.

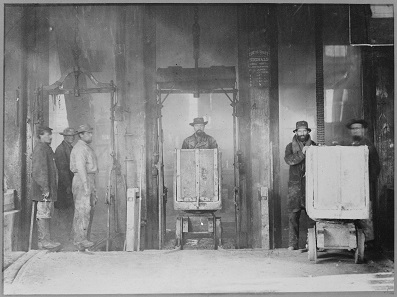

Return with packed box-cars. Photograph: National Archives and Records Administration 519526 / Wikipedia.

Fortunately, the silver mines of the city were a favorite subject-matter of magazines that came into being at that time. So we can look at pictures of the miners and their work.

Not to mention the report written by Mark Twain, who always makes good reading. He had worked in the Comstock Lode himself. When he realized that working in the mines was quite tedious and, what is more, not lucrative from the financial point of view, he signed up as a reporter for the Territorial Enterprise in Virginia City in 1862. It is fun to read his account of this time, which, in terms of mockery, is no way inferior to his travelogues from abroad. Therefore, as eye witness, Mark Twain gets a chance to speak. We quote a small excerpt taken from Chapter 52 of “Roughing it”:

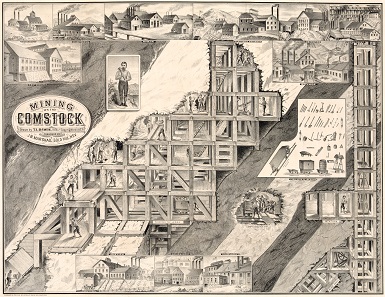

Probably the most famous depiction of the Comstock Mine. The mined ore deposits were underpinned with a standardized framework to prevent a collapse. Source: Wikipedia.

“Virginia was a busy city of streets and houses above ground. Under it was another busy city, down in the bowels of the earth, where a great population of men thronged in and out among an intricate maze of tunnels and drifts, flitting hither and thither under a winking sparkle of lights, and over their heads towered a vast web of interlocking timbers that held the walls of the gutted Comstock apart. These timbers were as large as a man’s body, and the framework stretched upward so far that no eye could pierce to its top through the closing gloom. It was like peering up through the clean-picked ribs and bones of some colossal skeleton. Imagine such a framework two miles long, sixty feet wide, and higher than any church spire in America. Imagine this stately lattice-work stretching down Broadway, from the St. Nicholas to Wall street, and a Fourth of July procession, reduced to pigmies, parading on top of it and flaunting their flags, high above the pinnacle of Trinity steeple. One can imagine that, but he cannot well imagine what that forest of timbers cost, from the time they were felled in the pineries beyond Washoe Lake, hauled up and around Mount Davidson at atrocious rates of freightage, then squared, let down into the deep maw of the mine and built up there. Twenty ample fortunes would not timber one of the greatest of those silver mines. The Spanish proverb says it requires a gold mine to “run” a silver one, and it is true. A beggar with a silver mine is a pitiable pauper indeed if he cannot sell.

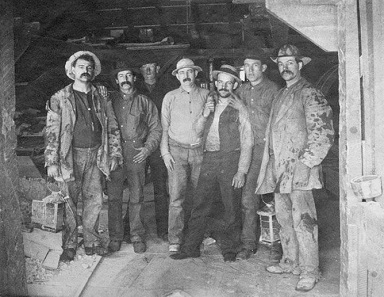

Miners of the Gould and Curry Mine. Because of the intense heat deep down, they do not wear any outer garments. Source: Wikipedia.

I spoke of the underground Virginia as a city. The Gould and Curry is only one single mine under there, among a great many others; yet the Gould and Curry’s streets of dismal drifts and tunnels were five miles in extent, altogether, and its population five hundred miners. Taken as a whole, the underground city had some thirty miles of streets and a population of five or six thousand.

Seven miners of the Comstock Lode. The image’s original caption read: To Labor is to Pray. Source: Wikipedia.

In this present day some of those populations are at work from twelve to sixteen hundred feet under Virginia and Gold Hill, and the signal-bells that tell them what the superintendent above ground desires them to do are struck by telegraph as we strike a fire alarm. Sometimes men fall down a shaft, there, a thousand feet deep. In such cases, the usual plan is to hold an inquest.

Miner of the Comstock Mine. Photograph: National Archives and Records

Administration 519527 / Wikipedia.

If you wish to visit one of those mines, you may walk through a tunnel about half a mile long if you prefer it, or you may take the quicker plan of shooting like a dart down a shaft, on a small platform. It is like tumbling down through an empty steeple, feet first. When you reach the bottom, you take a candle and tramp through drifts and tunnels where throngs of men are digging and blasting; you watch them send up tubs full of great lumps of stone–silver ore; you select choice specimens from the mass, as souvenirs; you admire the world of skeleton timbering; you reflect frequently that you are buried under a mountain, a thousand feet below daylight; being in the bottom of the mine you climb from “gallery” to “gallery”, up endless ladders that stand straight up and down; when your legs fail you at last, you lie down in a small box-car in a cramped “incline” like a half-up-ended sewer and are dragged up to daylight feeling as if you are crawling through a coffin that has no end to it. Arrived at the top, you find a busy crowd of men receiving the ascending cars and tubs and dumping the ore from an elevation into long rows of bins capable of holding half a dozen tons each; under the bins are rows of wagons loading from chutes and trap-doors in the bins, and down the long street is a procession of these wagons wending toward the silver mills with their rich freight.”

The San Francisco Speculator. From J. Ross Browne, A Peep at Washoe, published in 1861.

Mark Twain says it: The silver mining in Virginia City had nothing to do with the scratching on the surface, as it had been done in the early years of the California Gold Rush. Exploiting the enormous silver deposits required money, lots of money. That money was collected in the stock exchange of San Francisco where shares in the claims could be bought. The problem was that one claim contained a legendary Bonanza, whereas the other did not. And who would have sold a share in a profitable claim? The only hope was for the claim, just purchased on the cheap, to turn out a bonanza.

It was a game of chance – with marked cards. Men were doing rich. But even more men lost their money.

The private stamp mill of James Fair, one of the so-called “Silver Kings”. Photograph: UK.

This was because a group of insiders monopolized their knowledge and bribed enough miners to stay better informed than the general public. James Fair, for example, who started as a penniless Irish immigrant but made his way into the U.S. Senate, possessed a small stamp mill in his well-shielded backyard, with which he could assayed the silver content of a newly-opened mine himself.

A box-car from the Comstock Mine. Photograph: UK.

This private stamp mill is on display in an incredibly packed museum that bears the beautiful name “The Way It Was Museum”. It houses a wealth of techno-historical treasures.

An assay furnace that almost looks like a doll stove. Photograph: UK.

Exhibits include, for example, two contemporary assay furnaces. Taken at that time, there are plenty of images of such objects extant. But only when you stand in front of such a furnace you realize that they actually are not much bigger than a doll stove.

The Mackay Villa. Photograph: UK.

Let us get back to the silver kings. The most famous of these was John William Mackay, whose villa can still be marveled at in Virginia City. He invested his money in the transatlantic cable that connected the Old and the New World for 25 cents per word.

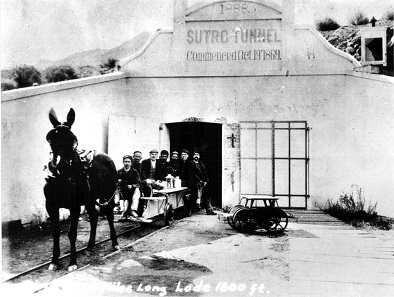

The Sutro Tunnel – a masterpiece of engineering. Photograph: UK.

Another contractor was Adolph Heinrich Sutro, a Jew of German origin, who immigrated to the United States at the age of 20. He had the idea to de-water and de-gas the shafts of the Comstock Lode through a long tunnel running underneath the mine.

Passage through the Sutro Tunnel. Source: Wikipedia.

After the tunnel was completed, he also used it to transport – of course against a fee – those people who wanted to take a shortcut to Virginia City. Sutro earned good money. And once he saw that the boom was drawing to a close, he sold his shares.

Legacy of Adolph Sutro: Cliff House, favorite restaurant with the people living in San Francisco. Photograph: UK.

He invested in real estates, located where San Francisco was expanding to a few years later. Sutro grew even richer and invested a marginal fraction of his wealth into attractions with public appeal, like the Sutro Baths or Cliff House, and had himself elected mayor in 1894.

Most of the silver kings converted their enormous wealth into political influence. No wonder that they managed to defer the adoption of the pure gold standard for the United States. To support silver mining, the Bland-Allison Act stipulated the purchase and coining of silver in the amount of two to four million dollars each month. When, in 1893, Congress ceased coining silver, the Comstock Lode was depleted and the ones who had made a profit invested their assets in other things than silver mining.

You can learn more about Virginia City on the website of its tourism commission. You will also find information on all attractions and the relevant opening hours.

A very good summary of the Comstock Lode is given in Wikipedia.

If you want to read Mark Twain’s “Roughing it”, you can find it in the Project Gutenberg.

At least as good a read is the Gray Brechin’s study of the influence of the silver kings in San Francisco. You can order the book at Amazon.

And may I recommend a hotel in Virginia City? We were very happy with the service at Silverland Inn & Suites.