On August 29, 1526 Louis, King of Bohemia, Hungary and Croatia, met his death in the Battle of Mohacs against the Turks.

Counts of Schlick. 1 ½ talers 1526 on the death of Stephan von Schlick in the Battle of Mohacs. Legend (in translation): In the year of our Lord 1526 at the age of 40 he suffered death while fighting for his country against the Turks. From Künker sale 289 (March 14, 2017), No 1534.

Strictly speaking, Louis’ order of succession was regulated. He had stipulated that his brother-in-law, Ferdinand I from the House of Habsburg, was to become his successor. The Hungarian estates, however, thought differently. They believed the contract to be null and void and decided to nevermore elect any foreigner as their king. Only a Hungarian would be qualified to assume this office.

1729 Portrait of John Szapolyai.

In a second step, the estates elected the Voivode of Transylvania, John Szapolyai, king. Back then, he was the richest member of his country’s aristocracy and possessed an army. He benefited from a logistical mishap that led his army to arrive in Mohacs too late to be slaughtered, too.

Ferdinand I. Reichstaler, posthumous striking from 1573/1576 Hall. From Künker sale 292 (March 16, 2017), No 5949.

Of course, Ferdinand I insisted on his right. He was the brother of Charles V meaning he had resources in abundance. And so, it was of little concern to him that, in his election in December 1526, it was a mere handful of powerful Hungarians who supported him. That could be changed. Ferdinand led an army to Hungary and took one castle after another.

The opinion of the assembly of the estates, therefore, swung when, in newly-captured Buda, he explained why he was entitled to the throne. They accepted him as their king and thus Ferdinand could have considered himself the sole rightful King of Hungary had it not been for John Szapolyai.

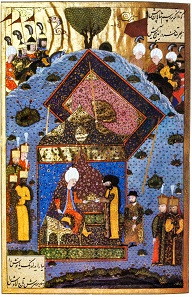

Suleiman the Magnificent passes the crown of Hungary to John Szapolyai. Contemporary Turkish miniature.

John Szapolyai turned to the one and only ally left, the Turkish Sultan against whom the Hungarians had striven on the battlefield of Mohacs a moment ago, and asked him for his help. It was granted. Suleiman requested John to make the oath of fealty and led an army himself towards the West.

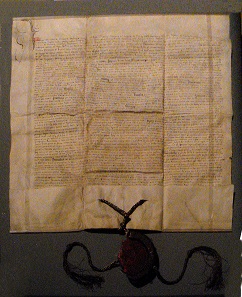

Treaty of alliance between John Szapolyai and Francis I of France.

Nothing could be more wrong than thinking that this war was a clash of religions. On the contrary, it was all about the question whether Hungary would become subject to the rule of the Habsburgs or, rather, the Ottomans. It was a question of power. This is illustrated by a contract between John Szapolyai and the Christian King Francis I of France who was a firm opponent of the Habsburgs. In the battle for Hungary, France fought on the side of the Ottomans.

Nevertheless, there is a reason why Charles V brother of Ferdinand stressed the fact that this war was against the enemies of Christianity. This was the only legal way to demand military and financial help from the empire’s estates.

Ferdinand I. Siege coin of 2 ducats 1529. 3rd known specimen. From Künker sale 289 (March 14, 2017), No 1535.

Suleiman didn’t meet with a great deal of opposition. In Mohacs, Szapolyai paid homage to the Ottomans. One fortress after another fell, and, on September 26, 1529 the Turks were at the gates of Vienna.

Panoramic view of the city of Vienna at the time of the first Siege of Vienna. Wien Museum.

The majority of people living in Vienna had fled, including Ferdinand I with his courtiers of course. Of the 3,500 men of the urban militia only 300 remained. Of the promised imperial army a group of a hundred arrived just in time. The main burden of defense was borne by 12,000 well-paid German and Spanish mercenary soldiers.

Ferdinand I. Siege coin of 1 ducat 1529. From Künker sale 289 (March 14, 2017), No 1536.

For this reason, a large emission of siege coins was issued, not only in gold but also in silver, to ensure that the soldiers could buy the necessities of life instead of having been forced to loot. Many of these siege coins have survived into our times. For centuries, they have been preserved with awe, as a memento of the “great victory of the Christians”.

Ferdinand I. Siege coin of 1 ducat 1529. From Künker sale 289 (March 14, 2017), No 1537.

The nearly 17,000 soldiers in Vienna were faced with the Turkish army consisting of about 150,000 combatants. What separated them were the city walls which were quite impressive ones. What’s more, the heavy artillery of the Turks had gotten stuck during the advance through the muddy Danube wetlands. And so the Turks resorted to a technological alternative: They dug mines, tunnels below surface that were planned to reach the city walls, to cause the fortifications above to totter upon the well-directed collapse of the tunnels.

Ferdinand I. Siege coin of 1/2 ducat 1529. From Künker sale 289 (March 14, 2017), No 1538.

The city’s population, however, received help from miners from Schwaz in Tyrolia. They knew precisely how to dig and support galleries. The Schwaz miners responded to the Turkish mines by digging countermines. They constructed their own galleries to find and destroy the enemy’s mines way before the city wall where they couldn’t do any harm. We can’t imagine the underground fights in the narrow galleries, illuminated by the flickering light of the miners’ lamps only, horrible enough. It was not possible to use fire weapons, to prevent any risk of the explosives detonating.

On October 12, 1529 the Turkish army successfully breached the city wall. But the garrison managed to beat back their assault. And Suleiman summoned his crown council. Autumn was approaching. Supplies for the winter weren’t backed, and so it was decided to withdraw the Turkish army. A victory? A defeat?

Religious medal Sonntagberg by P. Seel (middle of the 17th cent.). From Künker sale 289 (March 14, 2017), No 1547.

Naturally, the Christians considered themselves victorious and glorified the rescue of Vienna through numerous legends. One of these is depicted on this religious medal: Turkish horses are said to have been going down on their knees in front of the Pilgrimage Church of Sonntagberg and refused to further carry their riders about to plunder and heist.

Ferdinand I. Siege coin of 6 kreuzers 1529. From Künker sale 289 (March 14, 2017), from Lot 1543.

Actually, the situation was anything but clear. After the withdrawal of the Turks, Vienna was almost stormed by mutinous imperial troops. Having arrived too late, they didn‘t receive their five-time “storm salary”. Only two weeks later, their claims were reduced and satisfied, and so they withdrew.

Medal on Wilhelm Freiherr von Rogendorf, commander of the imperial cavalry during the Siege of Vienna. From Künker sale 289 (March 14, 2017), No 1551.

At any rate, Vienna was not taken and the Habsburgs were forewarned. When Suleiman sent a second army in 1532, it didn’t reach Vienna. It was crushed in the Battle of Fahrawald. The main reason was that Charles V was able to mobilize the joint army of the German Empire, and for that he paid by concluding the Peace of Nuremberg with the Protestant princes. The Reformation most likely hadn’t become established so quickly had it not been for Charles V being forced to get the Turks off his brother Ferdinand’s back…

Map of divided Hungary. Source: PANONIAN / CC0

Hungary was divided in 1533. Habsburg got a piece of Croatia and the city of Agram and a small fraction of Hungary roughly extending to Lake Balaton. The remaining major part was administered directly by Constantinople or through Christian vassals. Does this peace deserve to be called a Christian victory?

The Künker Auction at which these coins will be offered can be found here.

And the relevant CoinsWeekly auction preview can be read here.