by William McKivor

A short time ago a discussion was held on these pages concerning the donation of material to museums, and the problems that museums have in funding, space for exhibits, and in hiring and keeping curators. As I was the one who basically said to consider what you were doing before turning all over to a museum, I do need to clarify a couple things. In reading the answers to my letter, I quite agree with the gentleman at the Jewish museum, and the collector who found a perfect fit for his material. So, yes, if the museum fits, as they say, donate away!! I was of course not considering any type of museum except one that was Numismatic, or had a good numismatic section. All my curator friends are located in such museums, making their recommendation to me all that more important.

I was then invited to share an item from my collection with the readers of Coins Weekly, which caused an internal debate for about a week. I finally decided that, of all the items I own that came from the proprietors and builders of the Soho Mint, the most important item in my view is a medal. The piece pictured is one that was owned by Matthew Boulton, and put aside by him.

This medal was struck at the Soho Mint in 1803, during an argument conducted in three countries in three languages on two medals!! Matthew Boulton, depicted on the obverse of the medal above, was at the forefront of the Industrial Revolution. He and his partner, James Watt the engineer, had worked for many years perfecting the steam engine. By 1785, they had examples of their engines at work in mines from Cornwall to Scotland, and were beginning to get them into other commerce. Hooked up to knitting machines, milling machinery, and even a coin press, they were beginning to see the fruits of their labors.

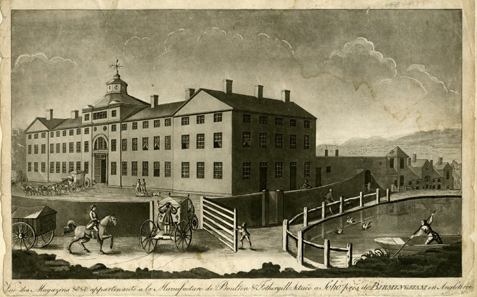

The Soho Mint by Francis Eginton, 1773. British Museum, London. Source: Wikipedia.

Boulton built a mint on their property, called the Soho Mint. Completed in 1789, Boulton wanted to coin for the world, beginning with England. He also wished to alleviate the proliferation of counterfeit coins, which were at the time considered to make up over 50 % of all coins in circulation.

While experimenting with the new steam powered mint, he took other contracts. The first thing to be struck on a steam press was a copper trade token, most likely for the Cronebane Mines, but possibly for Charles Rowe at the Macclesfield mines. He was given a contract to strike both, and the dies were sent to him. These were to be struck out of the collar, as there was no self ejecting collar yet invented, which kept him from speeding up the presses.

In light of this need, Boulton hired a engineer from France, one J. P. Droz, who showed him a multi-step press and coin ejecting collar that, well, was not quite perfected – but when it was, Droz assured him, Boulton would have his automatic coin ejecting collar. Droz also held that he was the premier engraver and die sinker in the world, and his new press and new collar would change the way money was struck. Boulton hired him.

Promises are about all that Boulton ever got from him. The special press and collar was always “close to ready” but never completed, his die work was fine, if you could get him to do it – and finally Boulton simply called an end to the association, paying him off for work never done and letting him go.

Droz found a home at the Paris mint, gaining as good a reputation there as the bad one he had earned in England.

In 1803, Droz made a pattern coin for Spain, in an attempt to gain a coinage contract from Spain for the Paris mint. On it, he listed a lot of things that Boulton had done, and called them his own, the self ejecting collar among them. He said that anyone else claiming these things was a fraud. All of this was on a French pattern medal or coin, and in Spanish. Boulton found out about it.

Boulton immediately answered, in French, on a medal made at the Soho Mint. Pictured above, the photo has information on the machinery used, the speeds involved, and the number of coins that could be produced. In French, with Boulton planning to send copies there to refute the claims of J. P Droz, translation of the reverse reads “In 1788 M. Boulton, Soho, England, made a steam machine for coining money, and in 1798 a superior one. Both machines can be worked by children with ease, and the speed increased to the degree required. The circles mark the diameter of the pieces, and the figures the number which can be struck per minute” This establishes a time line for the beginnings of steam powered coining, and the numbers could only have been accomplished with a self ejecting collar.

A letter from a workman at the mint to Boulton, who was in London, tells that shortly before 4 PM on the second Tuesday in October, 1790, the collar finally worked, and was in use. This invention alone forecast the beginning of modern coinage. No longer did a pressman or helper risk their fingers taking coins out as they were struck – the new collar allowed faster press speeds which the steam engine could supply.

The firm of Boulton and Watt not only coined money for other countries, trade tokens, and medals, but also their manufactory built steam engines for all trades, and even manufactured complete mints!! They built entire mints for Russia, Denmark, India, Mexico, Bolivia, and even, finally, a new Royal Mint in England.

One that got away was the United States, as the war of 1812 stopped negotiations, and the USA did not gain a steam powered mint until 1836. At one time in the early 1800’s Boulton and Watt were responsible, in one way or another, for nearly half of the world’s coinage. To say they achieved the minting success they were looking for seems correct, though it was, from their point of view, a very difficult road.

Matthew Boulton (1792), by Carl Frederik von Breda. Source: Wikipedia.

My collection consists of many medals, tokens, and coins struck by the Soho Mint from 1789 to the late Soho period in the 1820’s, and owned by the proprietors. Many of them have copper shell boxes, many have paper wraps signed by the owners of the mint or perhaps in some cases a secretary, all put aside to keep by the families.

James Watt, Jr, was the only true collector of the four owners, Boulton, Watt, and the two sons, Matthew Robinson Boulton and James Watt Jr. A sale of the Watt family items was held in London at the auction house of Morton and Eden on November 14th, 2002.

The new building of the Birmingham Mint, once Soho Mint. Photo: Oosoom/ Wikipedia.

The Boulton family material was held by London artifacts dealer Tim Millett, and between the auction and dealing with Tim, I managed to buy a good amount of the Boulton, and some of the Watt material.

Boulton and Watt sat at the pinnacle of the industrial revolution, and at the forefront of modern coining. They were held in esteem at the time, over 200 years ago, and are still held that way now. I was very lucky to have been able to gain a nice collection of items owned by these two families.

I would be happy to share it with the readers of this column at www.thecoppercorner.com – click on the Boulton and Watt pages, for a small history, and a view of many of the items in my collection.

Suggested Reading:

- Richard Doty, The Soho Mint and the Industrialization of Money, Smithsonian Institution, British Numismatic Society, Spink, London 1998.

- George Selgin, Good Money – Birmingham Button Makers, the Royal Mint, and the beginnings of Modern Coinage, Independent Institute, 2008. Soft cover, 2011.

References used:

- The Token Coinage of Warwickshire, W.J. Davis, Birmingham, 1895.

- The Soho Mint and the Industrialization of Money, Richard Doty, London, 1998.

If you are interested in the Soho Mint, visit its website!