The history of Austria’s paper money from the beginning of the 18th century onwards is characterized by many ups and downs, by strong and soon-after fading trust in the newly-introduced banknotes which, because of the war, were issued in huge numbers, from printing presses that were constantly running at full blast. At the end of 1797, close to 75 million guldens in paper money were already in circulation. The annual government spending had increased from less than 100 million guldens (at the end of Empress Maria Theresa’s reign) to 572 million guldens in 1798 (under Francis II).

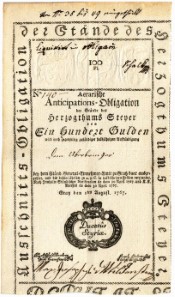

Lot 5273. Aerarische Anticipations- & Domestical-Obligation at 100 guldens from the duchy of Steyer 1767, and Lot 5274. Wiener Stadtbanco 10 guldens 1784.

These large amounts could only be handled with paper money. Gold and silver coins vanished over time, replaced by Vienna Bancozettel [literally “banknotes”] and copper coins. In 1810, not unrelated to the war against Napoleon, the paper money in circulation already amounted to over a billion guldens.

Numerous milestones in the monarchy’s monetary history can be listed chronologically:

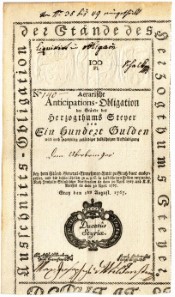

Lot 5282. Einlösungsschein at 1 gulden 1811, and Lot 5283. Anticipationsschein at 2 guldens 1813.

The state bankruptcy in 1811 led to the replacement of the old Bancozettel with newly-issued Einlösungsscheine [literally “redemption notes”]. Thus, the Bancozettel were devaluated to a fifth of their face value. Emperor Francis I supposedly said about this: “Whatever. A bankruptcy is a tax like any other. You just have to arrange it in such a way that everybody loses the same amount!” The government also introduced another currency, the Anticipationsscheine [literally “anticipation notes”].

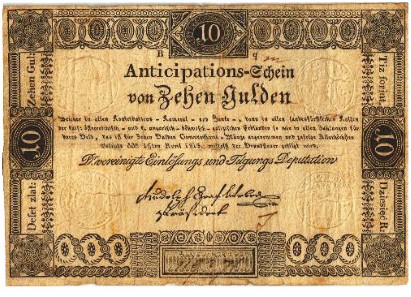

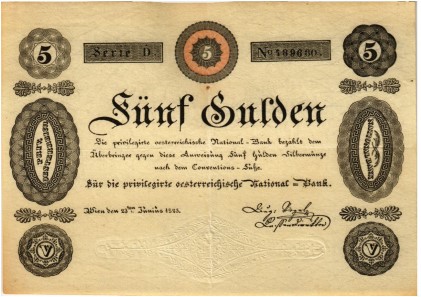

Lot 5284. “Privilegirte Österreichische Nationalbank”, 5 guldens 1825.

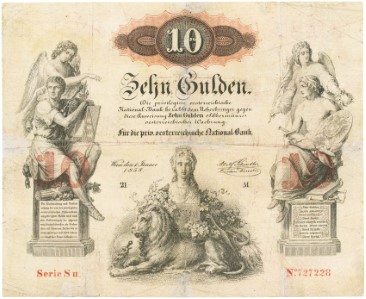

Mid-1816, the Austrian central bank “Privilegirte Österreichische Nationalbank” was founded with the aim of ensuring that no more paper money would be issued at forced exchange rates.

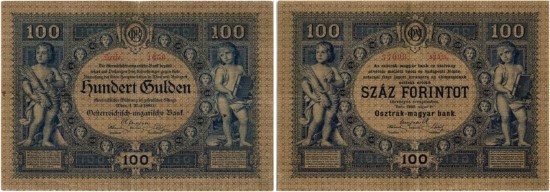

Lot 5310. Österreichisch-Ungarische Bank, 100 guldens/forints 1880 // Lot 5314. 100 kronen/corona 1902.

From 1848 onwards, during the years of wars and revolutions, the large empire was forced once again to issue interest-bearing and non-interest-bearing Cassa-Anweisungen [literally “bank payment orders”] and Reichsschatzscheine [literally “empire treasury notes”]. Besides, there were special editions for Hungary and the territories of Lombardy–Venetia. Small denominations increasingly found their way into the local money circulation in the form of emergency money editions from municipalities and even privates. In 1857, the gulden at 100 kreuzers (as opposed to 60 kreuzers before) was first introduced as Austria’s currency; in 1878, the Österreichisch-Ungarische Bank [Austro-Hungarian bank] was founded; from 1892 on, the gulden at 2 kronen was fixed as Austria’s currency; and with the beginning of 1900, the krone became the only legal monetary unit.

Lot 5340. Österreichische Nationalbank, 50 schillings 1935.

Then came World War I, with an initial banknote circulation of about 3 billion kronen, which increased to over 40 billion by the end of 1918. The collapse of the monarchy changed everything all over again. In the beginning, the newly-created countries continued to use old banknotes with special prints; once again, emergency money editions were printed, and on top of that, inflation began in 1921. Another monetary milestone worth mentioning was the introduction of the schilling currency in early 1925.

Lot 5342. Alliierte Militärbehörde, 1000 schillings 1944.

During the annexation of Austria into the German Reich starting in March 1938, the Reichsmark was introduced, and after World War II, the currency was once again schillings; in between, both the Western Allies and the Russian occupation authorities had printed banknotes as interim money. Nowadays, with the euro, there is finally a stable currency guaranteeing trustworthy money for the citizens from Vorarlberg to Burgenland.

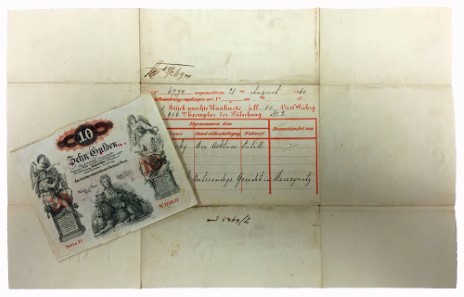

Lot 5293. 10 guldens 1858 (counterfeit and original) and envelope.

Such a huge empire, consisting of the most various cultures and peoples, numerous languages and social structures, understandably was hard to govern, and a joint monetary policy was an almost impossible task. Thus, it comes as no surprise that forgers took advantage of the banknote system’s weaknesses, starting with Napoleon who tried to harm the economy of the countries that were to be occupied with forged documents, up to more or less talented money counterfeiters. The most famous counterfeiter of Austrian banknotes was Peter von Bohr (1733-1847). With great effort, the authorities tried to take the forgeries out of circulation and get a hold of their criminal producers. And, as is customary for a well-organized state with plenty of civil servants, everything was documented, centralized and added up. For example, the envelopes in which the counterfeits were kept and then sent to Vienna are interesting historic documents.

Looking back, Austria’s banknote history which, for the uninformed, may seem quite chaotic, does have its charm. How about making this a new specialized field of collection? On October 25, 2018, the 52nd auction of the Zurich-based Sincona AG will be held. Among numerous banknotes as well as stocks and bonds from all over the world, there are also 78 lots of Austria, telling of the partly chaotic history of the alpine republic’s banknotes.

The auction catalog is available online.