On March 11, 2019, the Osnabrück auction house Künker is auctioning off a sestertius of Vespasian, with a well-known topic on its reverse side. The Emperor stands as triumphator to the right with spear and parazonium (= a dagger that was used as a mark of rank in the legions), resting his foot on a helmet. In front of him, a crying woman is crouching underneath a date tree, which was understood as a sort of coat of arms for the province of Judea. The circumscription reads IVDAEA CAPTA, meaning Judea has been captured.

Vespasian. Sestertius, 71, Rome. Very rare. Extremely fine. Estimate: 50,000.- euros. From Künker auction 318 (11-12 March, 2019), No. 1093.

This iconic coin was struck in 71 AD in Rome on occasion of the triumphal procession of Vespasian and Titus after their victory over the Jews.

Vespasian. Denarius, 72/73, Antioch. Very fine / Extremely fine. Estimate: 250.- euros. From Künker auction 318 (11-12 March, 2019), No. 1097.

Titus. Denarius, 80/81, Rome. Extremely fine +. Estimate: 500.- euros. From Künker auction 318 (11-12 March, 2019), No. 1132.

The motif was later taken up again and again by Vespasian and Titus. The defeat of the Jews became a central motif of Flavian coinage. In the following, we will look at the reasons for that.

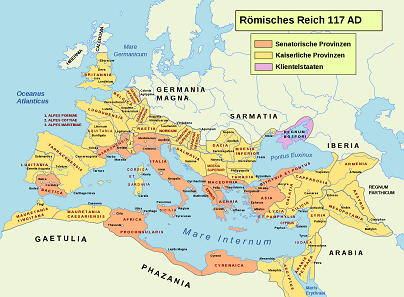

The Roman provinces at the time of Rome’s greatest extent in 117 AD. Map: Furfur / Andrei nacu, cc-by-sa 1.2.

Actually, Judea was quite far away from Rome. And actually, after the great wars of conquest under Augustus, the Roman Emperors were militarily rather set on preservation. So, actually, the conditions for a lasting peace would have been quite favorable, if it hadn’t been for one existential issue between Rome and the Jewish believers: How to define the relationship between subject, Emperor and God?

The center of the imperial cult in the province of Asia: the temple for Roma and Augustus in Ephesus. Claudius. Cistophorus, 41/42, Ephesus (Ionia). Rare. Nearly extremely fine. Estimate: 1,500.- euros. From Künker auction 318 (11-12 March, 2019), No. 1036.

Because in the entire Roman empire, it was the imperial cult that held together people of the most diverse religious beliefs. Not that a Spanish Celt, an Ephesian merchant or an ancestor of the Mauritanian Bedouins actually believed that the man in Rome with his wreath of laurels was in fact a god. And that wasn’t expected, either. What was expected, however, was the nominal homage, the celebration of the rites of the imperial cult as a sign of recognition. And part of that was, according to Roman ideas, placing a statue of the Emperor close to the local gods.

The Temple in Jerusalem. Model Israel Museum, Jerusalem. Photo: UK.

Which, for the Jews, was obviously impossible. And that is why Flavius Josephus’ story of the beginning of the great war between Jews and Romans may in fact be true: A Greek merchant is said to have provocatively sacrificed birds in honor of the Gods in front of the Jewish temple in Caesarea. As a consequence, the priest discontinued the prayers and offerings for the Emperor. As such, that doesn’t seem like a big deal, but add the fact that the people of the province were far from happy about the high taxes, and the affair quickly blew up. When the Roman governor Florus invaded the Jerusalem temple in order to cover the missing taxes with part of the (really big) temple treasury, the revolt broke loose.

In the “Antonia Fortress”, at the beginning of the war, a cohort (= in theory, 480 men) of the Legio X was stationed. Model Israel Museum, Jerusalem. Photo: UK.

The Roman garrison in Jerusalem was overrun, the Masada fortress captured. And in addition to the fight against the Romans, an internal Jewish conflict arose about whether or not to try and drive away the invaders.

A numismatic testimony of a free Jerusalem: Shekel, Year 2 (= 67/68), Jerusalem. From Künker auction 318 (11-12 March, 2019), No. 787.

Cestius Gallus, the governor of Syria, reacted quickly. He rapidly put up an army and invaded Judea. But, to the horror of the Roman authorities, the rebels gained a triumphant victory in the Battle of Beth Horon. 6,000 Roman legionnaires are said to have been killed. The Legio XII Fulminata lost its aquila. Cestius Gallus fled to Syria, and Simeon ben Gamliel proclaimed the Judean Free Government in Jerusalem.

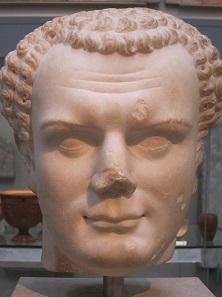

Vespasian. British Museum 1850-3-1.35. Photo: UK.

Even for an Emperor not particularly interested in power, but rather committing himself to the arts, like Nero, there was no choice but to send a general to crush the rebellion. Nero chose Vespasian, a proconsul of rather insignificant descent. His father had been a “mere” eques, for Roman standards quite a flaw. Thus, Nero thought, Vespasian was perfectly fit to lead a large army without becoming a dangerous competitor for the Emperor. A big mistake!

For Vespasian was an organizational genius, an unpretentious, results-oriented commander who took things like the common good seriously.

Upon his arrival in Judea, together with 60,000 men, he started to take back control of the rebellious province one city at a time. His task was facilitated by the fact that the different Jewish parties fought among themselves. And the victory was already foreseeable when Nero was declared public enemy.

Acte fetching Nero’s body after his suicide in order to bury him. The State Russian Museum, Saint Petersburg.

Actually, Vespasian had been ready to recognize Galba as Emperor. But before his son Titus even reached Rome in order to pay homage to him, Galba was dead, and Vespasian one of the most promising candidates for his succession. Due to his fight in Judea, he disposed of a large army. He had promising sons and good prospects of establishing a new dynasty. With the help of the governors of Egypt and Syria, he asserted his claims and had himself be declared Emperor by the army.

We don’t need to repeat in detail what happened in the Year of the Four Emperors. The result was that Vespasian seized power. And he now had quite a problem, because in terms of descent, career, personal appearance and connections, he was far behind what the Roman upper class expected of their Emperor. Nonetheless, in mid-70 AD, in the lex de imperio Vespasiani, the senate conferred on him all the powers of Princeps.

Titus. British Museum 1909.6-10.1. Photo: UK.

Around the same time, his son Titus conquered the city of Jerusalem. For the Jewish inhabitants, it was a disaster. Flavius Josephus writes about 1.1 million people being killed during the siege. Which is sure to be an exaggeration, but even the massacre of 15,000 to 20,000 people, as historians estimate today, is terrible! The city was destroyed, the temple razed to the ground. And from then on, the temple tax of 2 drachms had to be paid to the Roman Temple of Jupiter Capitolinus – what a humiliation!

The triumph of Titus. Painting on Limoges dinnerware of Jean de Court, 16th century AD. Photo: UK.

Even though some cities in Judea still weren’t conquered, Titus returned to Rome and, together with his father, celebrated their triumph in June of 71 AD. That was important for the new Emperor as well as all the other members of his dynasty.

Vespasian. Denarius, 69/70. Very fine +. Estimate: 250.- euros. From Künker auction 318 (11-12 March, 2019), No. 1089.

Because the Romans were convinced that a victory over foreign enemies was always linked to the favor of the Gods. Never would they have let Vespasian and Titus win if they hadn’t approved of their ruling over Rome. That was a true argument that no member of the Roman upper class could contest. Even though, for the average Roman, Judea was at the end of the world, it was after all the only victorious war of the last few years that the Romans had fought not against other Romans, but some sort of ideological opponent.

Vespasian. Quadrans, 71. Extremely fine. Estimate: 500.- euros. From Künker auction 318 (11-12 March, 2019), No. 1095.

That’s why the defeat of Judea plays such a crucial role in Roman propaganda. Again and again in the following years, the victory over the Jews was reflected on coins. In addition to that, there is the extraordinarily well-written account of events by a client of Titus’, named Flavius Josephus. He had his own reasons of highlighting the romantic elements of the war.

Thus, the first Jewish-Roman war received much more attention than any other military conflict during the entire Roman Imperial Period.

The Wailing Wall. Painting by Jean-Léon Gérome around 1880. Israel Museum. Photo: UK.

Which might be why we tend to slightly overrate this fight’s significance for Rome. Although one certainly cannot overestimate its meaning for those affected. Entire families were eradicated, the homeland destroyed, people driven away or sold into slavery – for its victims, every war is terrible!

The catalog of the Künker Spring Auction Sales is available online.

Our detailed auction preview provides an overview of the other pieces offered in this auction.

During her visit at the Israel Museum in Jerusalem, Ursula Kampmann got to see a coin hoard composed of shekels dating from the First Jewish War. Her report is available on CoinsWeekly.

“Siege coins” were minted in the fourth year of the war and they celebrate the Jewish holiday of Sukkot. David Hendin tells you more about the history of these coins on CoinsWeekly.