On 15 March, 2019, the Osnabrück auction house Künker is auctioning off a rare testimony of German history: The gold gulden struck in Frankfurt on occasion of Maximilian II’s coronation as King of the Holy Roman Empire, of which only two specimen are known, not only commemorates the first coronation of a German Emperor held in Frankfurt, but also a man who brought a period of peace to a religiously torn empire.

Frankfurt. Gold gulden 1562 on the coronation of Maximilian II as King of the Holy Roman Empire. Very rare. 2nd known specimen. Very fine to extremely fine. Price: 10,000 euros. From Künker auction 321 (15 March, 2019), No. 6646.

Maximilian II (*1527) was the eldest son of Ferdinand I, whom his older brother Charles V assigned the position of Emperor of the Holy Roman Empire. He grew up in Innsbruck, educated by important humanists. We do not know when exactly the young man first started to develop a tendency towards a liberal interpretation of the Catholic faith, but it is well documented that his family reacted immediately. Maximilian was sent off to strictly Catholic Spain. And Charles V took him with him when he fought the Lutheran princes in the Schmalkaldic War. However, Maximilian was not very popular with his imperial uncle, having demanded the protestant leaders’ release too vehemently.

Maximilian II at the age of seventeen. Oil painting by William Scrots. KHM.

Thus, it is no surprise that the family was suspicious of the young man. Could someone like him be trusted with the position of Emperor? Charles V insisted that Maximilian be skipped in the succession and that his own son Philipp II become Emperor after Ferdinand’s death.

Ferdinand I. Ducat 1557, Klagenfurt. Very rare in this grade. Extremely fine to FDC. Price: 1,000 euros. From Künker auction 321 (15 March, 2019), No. 6401.

“Not pontifical, not evangelical, a Christian” – what might seem to us today like a modern statement by Maximilian, was a scandal to his contemporaries. The Pope threatened to dismiss the Emperor who fathered such a son. Subsequently, Ferdinand I kicked out Maximilian’s court preacher, and Maximilian asked his protestant friends for help. But they had had enough with the loss of the Schmalkaldic War. Nobody came to help Maximilian, so he had no choice: In 1562, he pledged to remain adherent to the Catholic church. The family was reconciled, and the path was free for Maximilian to become ruler of the Holy Roman Empire of the German Nation.

Maximilian II as King of the Holy Roman Empire. Gotha.

On 20 September, 1562, Maximilian II was crowned King of Bohemia. On 28 November, 1562, the election as King of the Romans followed, without Cologne’s Archbishop Friedrich IV of Wied, whose predecessor Johann Gebhard von Mansfeld had died on 2 November, 1562. Even though the Cologne cathedral chapter elected a successor in a record time of 17 days, Friedrich IV did not make it to Frankfurt in time for Maximilian’s election.

The Emperor, the electoral princes and the city fathers of Frankfurt took advantage of that. For centuries, the Archbishop of Cologne had crowned the King in Aachen, because Aachen was part of his metropolitan district. However, what had made sense geographically at the time of Charlemagne, was obsolete in the 16th century from a logistic point of view. Frankfurt was better located and had better infrastructure. On top of that, it was also cheaper to have election and coronation at the same place. So, the politicians decided to have the coronation at the same place two days after the election. Of course, no precedent was to be set by that … Nonetheless, no king was ever crowned again in Aachen.

Coronation procession of Emperor Matthias I, 1612 in Frankfurt.

A later testimony gives insight on what the coronation festivities must have looked like. There is a detailed illustrated chronicle about the coronation of Matthias I, which leaves out neither the big feast and subsequent dance in the richly decorated city hall, nor the tournament and banquet in the Frankfurt city hall.

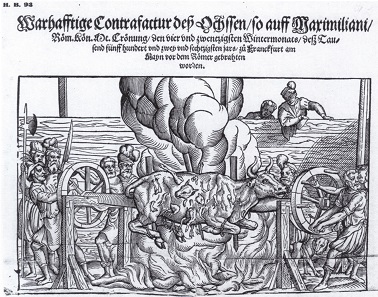

The banquet for the people on the Römer plaza. Single-sheet print from 1563.

Essential part of the public feast was a giant ox filled with other creatures. We know of deer, pork, veal and plenty of poultry to fill in the spaces in between. This ox made such a big impression that other Emperors insisted on having this pompous meal, too. Johann Wolfgang von Goethe himself, who witnessed the coronation of Joseph II on 3 April, 1764, tells about this custom in his autobiography Dichtung und Wahrheit: “About the roasted ox, a more serious battle was, as usual, waged on this occasion. This could only be contested en masse. Two guilds, the butchers and the wine-porters, had, according to ancient custom, again stationed themselves so that the monstrous roast must fall to one of the two” [translation by John Oxenford].

Coins being thrown into the masses. Detail of a copperplate engraving on occasion of the coronation of Matthias I, 1612.

It was part of the ceremony that the holders of the arch offices were at the new king’s service. The Elector of Palatine carried over a piece of the ox, the King of Bohemia fetched a cup of wine from the city fountain which, on occasion of the coronation, poured out the juice of the vine. And everybody waited eagerly for the Arch Treasurer to perform his duty of throwing one bag of silver coins and one bag of gold coins into the masses.

Was the item offered by Künker inside this bag, too? Or was it a gift to a subservient person? After all, the delegates from Nuremberg and Aachen received plentiful rewards for having brought the Imperial Regalia to Frankfurt.

With Maximilian II, the German Empire got a ruler who worked together with everyone in order to solve practical problems. Thus, it is quite a special historic testimony that Künker is auctioning off on 15 March, 2019. The coronation gulden represents a tolerant and pragmatic Emperor for whom religion was important, but not crucial.

You can read a comprehensive auction preview of the complete auction in CoinsWeekly.

And on the Künker website you will find the auction catalogues.