Olympian victor and hegemon of Greece

Macedonia – not long ago, that name hit the headlines of political news again. Utilizing catchphrases like “Macedonia remains Greek”, the national Greek propaganda tried to oppose the use of the emotionally charged name in naming a new state. In doing so, present day Greeks granted Macedonia something the members of the Argead dynasty, the Macedonian ruling house, had to fiercely fight for. All those Athenians, Thebans, Spartans and true Hellenes regarded the land at the border of the Greek world as extremely barbaric. After all, the Macedonians had not participated in the battle against the Persian King but had bowed to him. Plus, that underdeveloped part of the world had no democracy, no aristocratic rule or even a real tyrant. All that would have been decent – but: in Macedonia the king was elected by an army assembly. That was very shady.

Map of ancient Macedonia. Source: Wikipedia.

For that reason, there was a debate in the Ancient world whether the Macedonians were allowed to take part in the Olympian Games after all. By tradition, only true Hellenes could participate. According to the testimony of Herodotus V, 22, already the participation of Alexander I, King of the Macedonians 498-454, in the Olympian Games was discussed. He had to proof his Greek origin which he successfully did by affiliating the name of his – the Argead – dynasty to his descent from Argos.

A controversial Greek pedigree of a ruler in a semi-barbaric land is easy to live with if one possesses enough gold and silver mines and stays at home, as good as gold. However, if one attempts to gain hegemony over all Greek – and that is exactly what Philippos II did – that becomes a real problem.

Portrait of Philipp II of Macedonia. Ny Carlsberg Glyptothek. Image: Gunnar Bach Pedersen / Wikipedia.

Philippos II certainly made an effort to propagate Greek culture in his land. He conquered one city after another and established contact to the Pythia at Delphi. He even behaved like their defender when he fought the Phocians in 352 after they had looted the treasure at the Delphian temple to gain enough money for their soldiers. What Philippos deliberately concealed was that the battle was about the supremacy in Central Greece as well.

In his attempts Philippos not only used weapons and diplomacy but – like the Persians did once – his money as well. The Macedonian and Thracian phyla always had rich silver deposits at their disposal. In addition, Philippos gained a seemingly inexhaustible source of gold when he conquered the Pangaion Mountain on the mainland opposite the island of Thasos. The gold was supposed to flow to the Greek cities to further support the policy of the Macedonian King. Naturally Philippos tried to present himself in the brightest light possible on his coins – so he chose new images that stressed two aspects: for one thing that he was favoured by the gods, for another thing that he – without the slightest doubt – belonged to the Greeks.

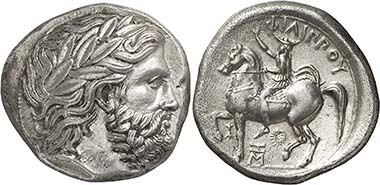

Tetradrachm of Philipp II, made posthumously c. 315/4 – 295/4 B. C. in Amphipolis. From auction Gorny & Mosch 146 (2006), 162.

The new tetradrachms, issued in 348/47 for the first time, continued to show on the reverse Zeus which the Macedonians were in rapport with. He was regarded father of the eponymous hero, Makedonos. Zeus’ appearance clearly reflects the intent. Depicted is a paternal looking man of middle ages with chin-length hair and beard. He wears the laurel wreath that was given to the victors in Olympia. Not only the laurel wreath points at Olympia, but his aspect in its entirety reminds of the statue created by Pheidias for Olympia.

The coin’s reverse refers to the centre of the Greeks, too. A young rider on horseback holds a long palm branch in his hand as sign of his victory. The coin therefore recalls the victory in Olympia Philippos achieved in 356. Plutarch, Alex. 3, reports that the Macedonian King received three important messages at the same time: Parmenion had defeated the Illyrians, his horse had been victorious in Olympia and he had begotten a child, the later Alexander. Philippos rated only the Olympian victory so significant to have it depicted on his coin. Philippos of course did not take part in the race personally but a professional equestrian riding his horse gained the victory. The win nonetheless dignified Philippos alone.

After all, for the Greeks a victory did not result from human effort but from divine favour. They granted the victory not the one with the best trainer, the best equipment or the best daily form but the one they deemed worthy or simply they liked best.

Temple of Olympia, on the pediment the depiction of Pelops prior to the chariot race.

Anyone visiting Olympia could see how little – according to the Greek view – the victory had to do with effort when he looked at the East pediment of the Temple of Zeus where a local tale was shown. Oenomaus, mythical ruler of the Olympia territory, was foretold by an oracle that his son-in-law would kill him. He consequently tried to prevent his daughter to marry and assigned all possibly candidates an almost unsolvable task: to defeat him and the invincible horses, which he had been given by the son god himself, in a chariot race. After Oenomaus had already defeated and killed 13 suitors Pelops, eponym of the Peloponnese, asked for his daughter’s hand. Since he saw no chance of succeeding, he bribed Oenomaus’ charioteer who consequently changed the wooden naves for waxen ones. Hence, the chariot lost the wheels under way and Oenomaus was killed. Zeus did not grant the victory the better but the one he had chosen. The depiction on the Temple of Zeus shows the two contestants prior to the start to both sides of Zeus who looks at Pelops because he had already decided which one was going to be successful.

Like Zeus once had decided to aid Pelops he made clear with Philipp’s victory that the Macedonian King was his new favourite. The Olympian victory therefore was not “only” an athletic success for the ambitious king but was regarded a political criterion, too. Whom the gods favour in a mirthful tournament they would grant their favour in battle as well, in negotiations – in everything a human might need divine support.

It comes as no surprise, then, that Philippos had the victory depicted on his coins since they were designed for the broad Greek audience. With his coins he bribed the Macedonian-friendly parties in the cities, and with them he paid his mercenaries. Soon, Philippos’ tetradrachms circulated in all cities.

Tetradrachm of Philipp II depicting the King addressing the army assembly, minted in Pella c. 359-355/4. From auction Nomos 2 (2010), 55.

They replaced his old coins whose reverse was politically not quite respectable: the image showed the Macedonian King addressing his army assembly. As stated above, democracy, aristocracy or tyranny, those were the forms of the Greek government. By stressing the elective monarchy the Macedonian King would have discredited himself. The Olympian victory was a much more suitable subject to be propagated on coins throughout Greece. The new tetrachdrachms were a real success and they continued to be minted after Philippos was already dead.

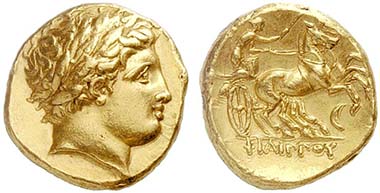

Gold stater of Philipp II, minted posthumously 336-328 in Amphipolis. From auction Lanz 148 (2010), 22.

The new gold coins, too, emphasized those two aspects Philippos wanted to hammer home to all Greeks: we Macedonians are Greeks like you and I, their King, am the gods’ favourite. Philippos utilized another victory he had achieved in Olympia. Plutarch, Alex. 4, 9, reports that the king had the victories his chariots had gained in the Olympian Games depicted on coins. Not only once but several times the gods conferred benefits to the ruler of the Macedonians. It was not solely Zeus who was on Philippos’ side. The obverse of the new gold staters shows Apollo with his juvenile face and the long hair bound by a laurel wreath. This is the master of Delphi looking at us. Philippos had always been on good terms with the Pythia, and after the defeat of the Phocians in 346 he even possessed two votes in the Delphic Amphictyony that supervised the oracle. According the hoard evidence, the new gold coins seem to have been issued since 345. Philippos had prepared his new role as hegemon of all Greeks well, economically and propagandistically. Everything was ready to attack the Persians to get the rich cities of Asia Minor under Macedonian protection. The preparations for a big campaign were already made when a disillusioned and abused boy called Pausanias, who once believed to possess the great king’s love, killed “unfaithful” Philippos. The king was a great man who came to a tragicomic end. His coins nevertheless continued to be minted. They were far too popular with the Greek cities for Alexander III renouncing them when he prepared the campaign against the Persians. More than 300 years later, Livy still speaks of the gold philippei that, after Macedonia had been defeated, were displayed in vast amounts to the marvelling Roman crowds in the triumphal procession.