by Vanna Arrighi

Since September 17, 2011 visitors can see a marvelous exhibition at Palazzo Strozzi in Florence. It is named Money and Beauty and is dedicated to the link between early modern banking and art. On exhibit is not only art, but documents, numismatists dream of like a book in which those responsible of striking coins have noted their decisions on the design. Vanna Arrighi has written a very special comment on this spectacular source for numismatics.

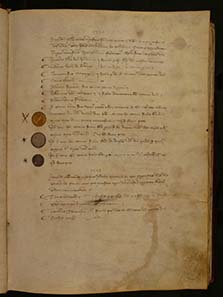

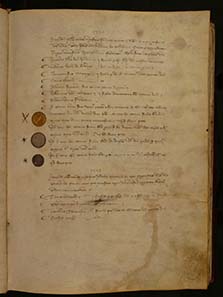

“Fiorinaio”. 1317-1834 parchment register, bound in leather and wooden boards; minute chancery in the different hands of the notaries who served the Mint Officials 47.5 x 35 cm Florence, Archivio di Stato, Ufficiali della moneta, later Maestri di zecca, 79, fol. 14r.

The Fiorinaio is a register containing copies of the various coins struck in Florence from the 13th to the 19th century, arranged in chronological order and interspersed by reports on appointments of the officials responsible for coinage, and rules governing their activity. These officials, called Signori della Moneta up to 1373 and Ufficiali della Zecca afterwards, were entitled to choose the symbols and decoration imprinted on the coins struck during their term of office.

The register was begun in the month of March 1317 by Ser Salvi Dini, at the time notary to the mint officials. On the first pages he transcribed earlier information and documents, dating back to1252, the year when the first gold florin was struck, and then continued to record current entries up to 1321 (fol. 11v). After this date the register was kept by others until 1834.

Before the 16th century, two officials were responsible for coining money, one designated by the Arte di Calimala (also called Arte dei Mercanti or Mercatanti, the international merchant’s guild), the other by the Arte del Cambio. The former was responsible for imprinting the so-called “sign,” or mark, on gold florins, while the latter did the same for silver alloy coins. They usually held their position for six months, although longer or shorter terms are documented. At first the coins were usually imprinted with imaginary designs but after 1375 it became customary to imprint the family coat of arms.

The two main officials were assisted by a staff of sentenziatori (judges), also calledassayers, approvers or revisers, responsible for quality controls of various kinds (weight, engraving, quality of the alloy); appraisers and repairers, who corrected any defects; and skilled labourers (smelters, engravers, incisors) who actually manufactured the coins.

Minting was done mainly at the initiative of private individuals, notably merchants and bankers, who, in need of cash, delivered gold and silver—in the form of metal bullion or foreign coins—to the mint, to have it melted down and cast in florins. When the coined money was consigned to its owner, the officials detracted a percentage destined in part to the city treasury and in part to the mint. In very rare cases, the Florentine government requested the coinage of money.

In republican times the mint was situated near Palazzo della Signoria, first in rented quarters, then, from 1363, in premises purchased especially for it. This register includes (fol. 70) the purchasing contract for a building in Via dei Forbiciai, that was to house the mint.

This article of Vanna Arrighi about the Fiorinaio comes from the catalogue “Money and Beauty. Bankers, Botticelli and the Bonfire of the Vanities, curated by Ludovica Sebregondi and Tim Parks, Florence, Palazzo Strozzi, 17 September 2011-22 January 2012, Florence, Giunti Editore, 2011, pag. 124.

If you want to know more about the exhibition, please read our article and click here.