Gotland was a special kind of island. Independent peasant families lived there on their own property for which they didn’t have to render any services to a landlord. Which in turn meant that they were able to conduct their own business, in which they were rather successful. Testimony of that are the over 700 treasures with around 180,000(sic!) coins that have been found on the island.

For a summary of Gotland’s history, please read part 3 of the “Numismatic Miniatures from the North”.

To learn about the history of Visby and Gotland in more detail, you should definitely visit the historical museum which, together with plenty of others, makes up the Gotland Museum. I neither can nor want to judge the modern art in Gotland – it simply doesn’t interest me enough. But the historical museum, that I can judge. And it is phenomenal!!!!

The historical museum is not only rich in unique objects, it is also didactically excellent, and everything is labeled in both Swedish and English.

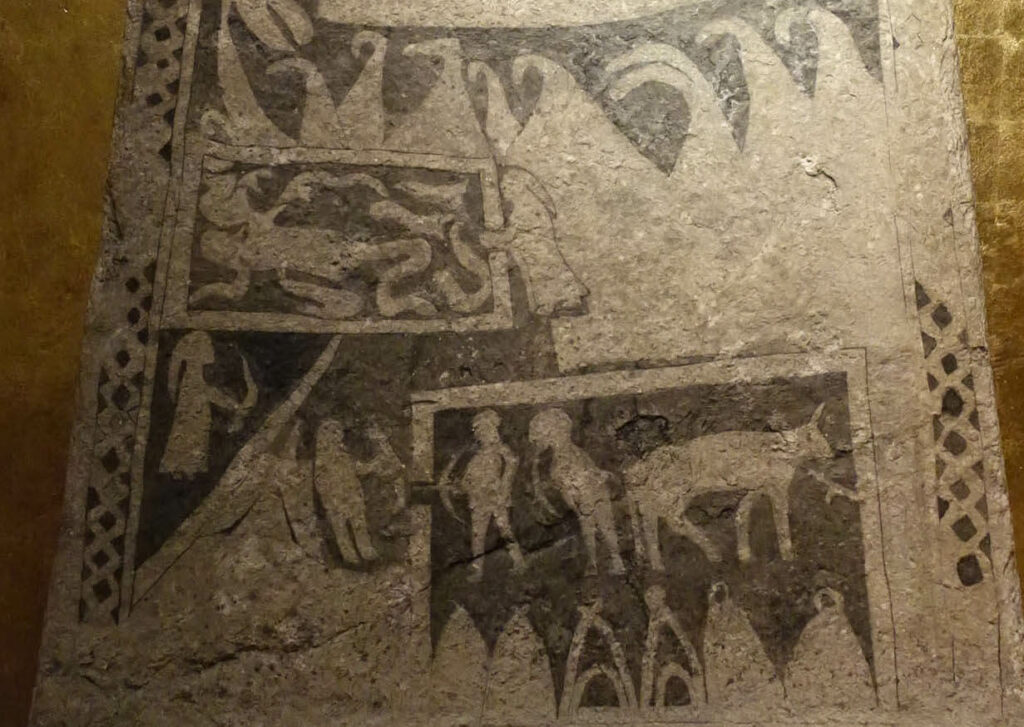

When you enter the first hall next to the ticket counter, you’re overwhelmed by the plentiful Gotland picture stones, the most interesting and best-preserved of which are assembled here. They were created between the 5th and the 14th century and bear witness to the wealth of the Gotland people and the courage with which they multiplied that wealth. Ships are often at the center of the images. We see them gliding along underneath billowing sails or driven forward by oarsmen’s powerful strikes.

Another theme often depicted is battle. One stone even tells of a man who was left in a snake pit. He is welcomed in Valhalla by a beautiful virgin – well, she isn’t all that beautiful on the stone, but we know how it was meant – with a horn filled with foamy mead.

Another theme often depicted is battle. One stone even tells of a man who was left in a snake pit. He is welcomed in Valhalla by a beautiful virgin – well, she isn’t all that beautiful on the stone, but we know how it was meant – with a horn filled with foamy mead.

Some of the hoards date back to Roman times, most of them are from the Viking era, i.e. from AD 800 till AD 1150. Already in Roman times, the Gotland men must have earned massive treasures as mercenaries, pirates and/or merchants, that probably weren’t of much use on the island. So they were buried, perhaps as nest eggs, in the ground.

To take a look at these treasures, the historical museum is the place to go! For there is a treasure room, exhibiting a marginal part of these riches. “Marginal” being relative: The room consists of numerous showcases where thousands of coins, ingots and valuables are on display.

The spectrum ranges from a hoard of Roman denarii to a magnificent Roman wine set adorned with a golden torc weighing 800g.

Now, a torc might make you think of a Celtic tribal chief, but that interpretation doesn’t fit here. The ring actually has a diameter of 24 centimeters, which should have been too wide even for the Viking with the thickest neck. Therefore, it is assumed today that this item was made for a statue. By the way, something similar is featured on the Gundestrup cauldron, which can also be viewed in the North, in Copenhagen …

Furthermore, you can admire some examples of the so-called “Scandinavian bracteates” in Visby. These aren’t coins in the actual sense of the word, but rather a derivative of the Roman gold medallions that were used to honor allied barbarians. Those who couldn’t get a hold of one directly from the Romans, had one made themselves – the style obviously being far from that of the Roman originals.

And talk about the medieval finds!!!! Some of them just are incredibly large. The Spillings Hoard, for example, contains about 67 – sixty-seven (!!!!) – kilograms of silver, the objects stemming from 20 different countries, mostly in the Orient.

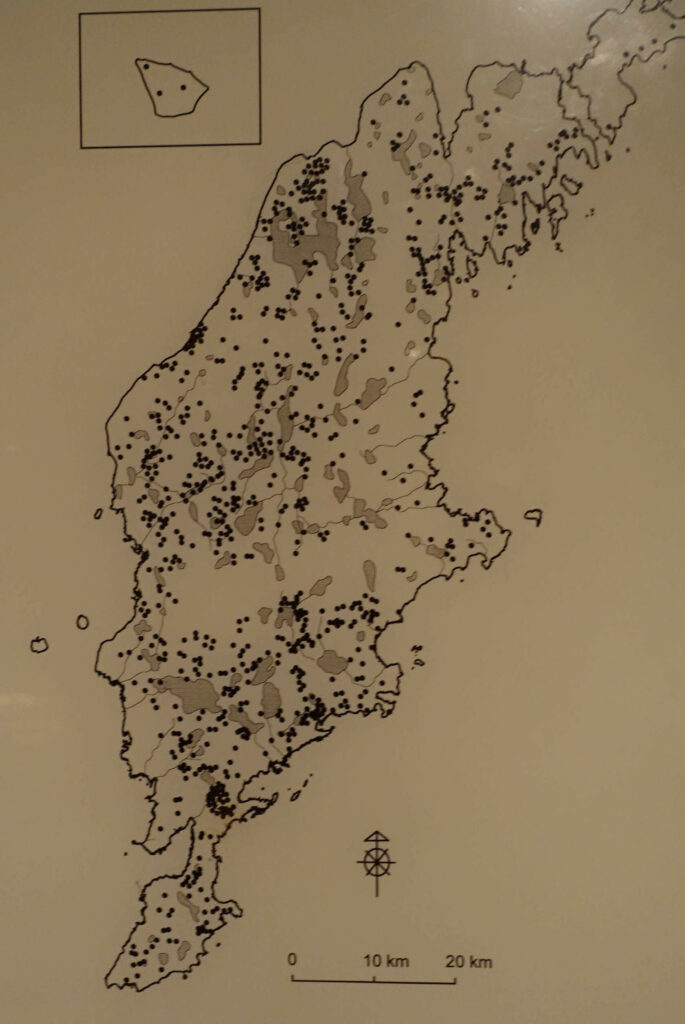

All these hoards were discovered – and this is descriptive of the social structure of Gotland – not in the city of Visby, but in the open countryside, scattered all over Gotland. From the 9th until the 11th century, the rich silver treasures were found in the heartland, and only from 1075 onwards, the findings of hoards concentrated more and more along the coast.

It was the wealthy trader-peasants who, as heads of their families, amassed, multiplied and buried the family riches. Through smart farming, they multiplied their assets and transported their goods not into the nearest city, but across the sea, in order to sell them at a larger profit. However, they don’t seem to have reinvested that profit, but instead hid it in the house as a family treasure. Why it was never unearthed again, who knows? Maybe the family father died at Visby while defending Gotland’s liberty, and forgot to tell his heirs the secret. Maybe the silver just wasn’t needed and therefore left hidden. Because in the Viking legends, unearthing a treasure always comes with dangers, too.

No need to go back to Siegfried and the Hoard of the Nibelungs. A different story is more present here: that of Stavar the Great. He defended his country against the Norwegian Viking Erik Jarl. And gave his life doing so. But in 1880, he appeared to his descendant (admittedly, the latter was quite inebriated at the time). Stavar promised the drunken Göran to give him the treasure, for he was his descendant. Göran, however, remembered that treasures were always associated with doom, and renounced. Thus, Stavar only gave him a few coins from the hoard and promised to try again with his descendants. Who in turn contacted the competent archeologist when they gave up the family farm in the 1950s. In no way did they want to lose the claims to their treasure. Unfortunately, I wasn’t able to find out whether they did indeed receive at least part of it when, in 1975, “their” treasure was found by playing schoolchildren on the property of their farm.

You have come to realize by now: It is worth not just staying in Visby but discovering all of Gotland. For Gotland not only offers the highest concentration of treasure cases, but also the sheer incredible number of over 100 Roman churches. The country was rich, very rich. And one might very well wonder if the number of hoards found receded so drastically after 1150 because the trader-peasants then preferred to invest in their salvation in form of a church.

These churches are all of quite similar design. They have a chancel, a nave and a front steeple whose first floor was often integrated into the church interior.

The masonry is remarkable. Its quality is incredible!

At least as meaningful are the numerous paintings that have been discovered in these churches.

The interior of the churches also presents a lot of similarities. Not just the richly decorated baptismal font with sculptures is exceptional.

The offertories are also interesting and in some cases elaborately designed.

What I found especially noteworthy was the typical Gotland “collection bag”, which is more of a “collection board”. To a board with carvings, a second, rimmed board is attached onto which a donated coin would be put.

But why were Gotland’s peasants so wealthy? There was of course the intermediate trade which can bring in a lot of money. Nonetheless, there had to have been some original products as a seed capital …

We found the answer to this question in the museum of Bunge, an open-air museum showing Gotland farmsteads from different eras. Aside from the fact that the island of Gotland is naturally fertile, and its fishermen surely caught lots of herrings that can be cured with salt and sold to all Christians who are regularly fasting, well, apart from that, Gotland’s peasants produced an essential good for the shipping industry: They boiled tar and shipped it, together with other consumer goods like beeswax, grains and rope, directly to the Baltic Sea harbors, in order to make their own profit. But as opposed to the trader-bankers from Italy, they didn’t invest the money they made this way in counts, but rather buried it in the ground.

Thus, Gotland became a true treasure island, which not only offers history and coins aplenty, but also the biggest treasure an island can offer these days: peace and quiet.

You will find all parts of our series about Sweden, its history and its coinage on this page.