On 13 May 1717, Maria Theresa was born as the second child of Emperor Charles VI. Her older brother had died shortly after his birth and there would not be any more sons. Therefore it was soon evident that she would be the next ruler of the Habsburg hereditary lands.

Maria Theresa at the age of 11, painting by Andreas Möller. KHM, Vienna.

The Pragmatic Sanction and the succession to the throne of Maria Theresa

At that point in time, this had only been possible for a few years. Her father Charles, who had been considered a possible claimant for the Spanish crown during the War of Spanish Succession, had experienced what it means for a country to see their ruling dynasty die out. That is why Charles, only 28 years old at the time, issued the Pragmatic Sanction in 1713, which entailed two main changes:

1) The Habsburg hereditary lands could no longer be split between different branches of the family.

2) If there was no direct, male heir, then female succession would be enforced.

Maria Theresa. Gold medal at 10 ducats 1741 by A. Widemann on occasion of her coronation as Queen of Hungary in Bratislava. Very fine +. Estimate: 4,000 euros. From Künker sale 294 (28/29 June 2017), No 3421.

This was already the case after Charles’ death in 1740. Of course nearly all European states were hoping to be able to draw an advantage from it and annex parts of the Habsburg Empire with all kinds of pretences – just like it had been done with Spain. Consequently Maria Theresa, the 23-year-old archduchess of Austria, Queen of Hungary and Bohemia, was forced to simultaneously fight against Prussia and Bavaria, Spain, Saxony, France, Sweden, Naples, the Electoral Palatinate and the Electorate of Cologne in order to maintain her country’s integrity.

After the end of the Spanish War of Succession, the Spanish Netherlands had gone to Austria. As a result, there are coins of Maria Theresa from Antwerp (mint mark: hand) and Brussels (mint mark: angel’s head): Maria Theresa. 2 Souverain d’or 1762, Brussels. Very fine / Very fine to extremely fine. Estimate: 600 euros. From Künker sale 294 (28/29 June 2017), No 3426.))

But she did not fully succeed. She had to forfeit Silesia and K?odzko, Parma and Piacenza. That was bad but not existence-threatening. Because of his early regulation of the line of succession, Charles VI had spared the Habsburg Empire the Spanish fate.

Maria Theresa. Reichstaler 1741, Vienna. Extremely fine. Estimate: 500 euros. From Künker sale 293 (27/28 June 2017), No 1620.

The mints of Maria Theresa

When Maria Theresa assumed office, she took over the denominations as well as the weight and fineness of her father’s coin. Thus the most important coin was the taler, which – as she confirmed in the coin instruction of 17 July 1741 – should be issued at 28.82 g of 875 silver.

Table of the most important denominations:

| Taler | Gulden | Quarter taler | 15 Kreuzer | 6 Kreuzer | Groschen | Kreuzer | Pfennig | |

| Taler | 1 | |||||||

| Gulden | 2 | 1 | ||||||

| Quarter taler | 4 | 2 | 1 | |||||

| 15 Kreuzer | 8 | 4 | 2 | 1 | ||||

| 6 Kreuzer | 20 | 10 | 2 | 2,5 | 1 | |||

| Groschen | 40 | 20 | 10 | 5 | 2 | 1 | ||

| Kreuzer | 120 | 60 | 30 | 15 | 6 | 3 | 1 | |

| Pfennig | 480 | 240 | 120 | 60 | 24 | 12 | 4 | 1 |

The coins of her father were the models for Maria Theresa’s first emissions: Charles VI. Ducat 1738, Kremnica. From Künker sale 294 (28/29 June 2017), No 3420.

Certainly, the ducat was still minted, but it was outside the system and was valued at four gulden nine kreuzers.

Charles VI. Reichstaler, 1739. Kremnica. Very fine to extremely fine. Estimate: 200 euros. From Künker sale 293 (27/28 June 2017), No 1619.

After the Austrian War of Succession and the first two Silesian Wars, Austria’s finances were ruined. Maria Theresa thus used an effective method to regenerate. In the 18th century, this method was to lower the silver content of the denominations and to mint more fractions, whose intrinsic value was far below its face value anyway.

Maria Theresa. Reichstaler 1751, Hall. Almost extremely fine. Estimate: 150 euros. From Künker sale 293 (27/28 June 2017), No 1628.

Maria Theresa actually issued three edicts in just four years: In 1747, she demanded that the minting of talers, half-talers and quarter-talers be limited in favour of fractions, in 1748 and 1750 she reduced the metal content of all coinages. In order for the officials to be able to recognise the “bad” coins, a saltire was put after the year. Of course this “secret mark” did not stay secret for all too long…

Maria Theresa. Ducat 1765, Kremnica. Almost extremely fine. Estimate: 400 euros. From Künker sale 294 (28/29 June 2017), No 3428.

However, the exchange rate of the golden ducat was not adjusted to the debasement of the silver coins, which lead to the gold coin becoming underpriced in Austria. Of course, as a consequence, there were a lot of gold coins taken out of the country – a lot more than the empress would have preferred.

Maria Theresa. Half-convention taler 1765, Günzburg. Almost extremely fine. Estimate: 300 euros. From Küker sale 293 (27/28 June 2017), No 1613.

In order to prevent this, the empress made a coin treaty with her neighbour, Maximilian III Joseph, Elector of Bavaria, on 21 September 1753. The two neighbouring states thus agreed that they would mint coins which were matching in terms of weight and fineness and could thus circulate in both countries. The taler was debased once more. Instead of the 28.82 g from the start of Maria Theresa’s reign, they decided on 28.06 g. The fineness was lowered from 875 to 833. The value of one ducat was fixed at 4 gulden (=2 talers) and 10 kreuzers.

The new denominations were thought out so well that Austria kept the regulations of 1753 for more than 100 years.

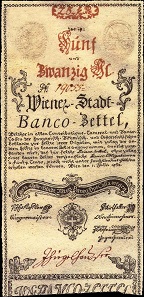

Bancozettel worth 25 gulden of the Vienna Stadt-Banco.

The Bancozettel

In 1763 the Seven Years’ War ended. It had left Austria with costs as high as 260 million gulden (= 130 million talers).While Frederick II mostly exercised coin fraud to meet the costs, Maria Theresa imposed a war tax. When this was not enough, she resorted to bonds. But the interest rates on these constantly increasing government bonds were quickly devouring more than half of the state budget. In 1761 alone, the new debt was 13 million gulden!

Maria Theresa thus had to find new ways. She decided to go with paper currency. The Vienna “Stadt-Banco” started giving out so-called “Bancozettel” in 1762. This worked well, since the state assured a high demand for them. One could pay taxes with them; some dues even had(!) to be delivered with one half the total amount in Bancozettel. Thus the demand increased even more, of course. If anyone had 200 gulden in Bankozettel, they could even exchange them for bonds at a 5% interest rate. This was so popular that in 1763, interest rates could be lowered to 4%. Bancozettel were traded with up to 2,5% agio! And whatever came back in Bancozettel to the Stadt-Banco was publically burnt.

It was until 1811 – almost half a century – that these Bancozettel were circulating, before so many banknotes were given out in the war against Napoleon that Austria had to file for national bankruptcy in 1811.

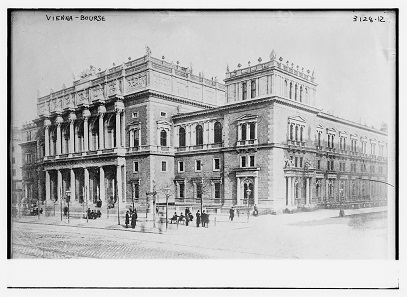

The Vienne Stock Exchange, built in 1877. Glass negative, 1910-1915. Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division, Washington, D.C. 20540 USA, hdl.loc.gov/loc.pnp/pp.print.

In order to simplify the trade with these papers and prevent secret speculations, Maria Theresa founded a stock exchange in 1771. This makes the “Wiener Börse” one of the oldest stock exchanges in the world. One could exclusively buy and sell government bonds, paper currency and foreign currency. Everything was managed by one exchange commissioner. Four brokers transacted business. Stocks however only started to come into play at the beginning of the 19th century.

Maria Theresa. Convention taler 1767, Vienna. Adjustment marks. Extremely fine. Estimate: 300 euros. From Künker sale 293 (27/28 June 2017), No 1633.

How much money does an Empress make anyway?

150,000 gulden (= 75,000 taler) – that is the amount Maria Theresa received each year from the “Geheimes Kammerzahlamt”. In addition, she got 8,000 gulden at the start of every month and 4,000 more gulden on the 15th of every month. All in all, the “Kammerzahlamt” paid her 324,000 gulden per year on total. By comparison, a day-worker would earn about 15 kreuzers, which is a quarter gulden, in the year of Maria Theresa’s death. A kilogram of bread cost about 4 kreuzers.

Francis I. 1/2 Reichstaler 1750, Graz. Very fine to extremely fine. Estimate: 150 euros. From Künker sale 293 (27/28 June 2017), No 1634.

But Maria Theresa still was not the rich one in the family. Instead it was her husband Francis I. He was doing well as a businessman and he encouraged both the nobility and the middle class to do the same.

He was running big model farms in today’s Slovakia, where fruit and wine were grown, livestock was raised and beer was brewed. He founded factories where majolica was made and cotton was processed. After his death in 1765, he left the incredible private fortune of 18 million gulden, which Maria Theresa used to restore the state finances.

Maria Theresa at the age of ca. 60 years. Painting by Joseph Rösch.

After Maria Theresa’s death, 3,943 gulden and 44 kreuzers were found lying around in Maria Theresa’s room, which could be interpreted as a sign that in 1780, when the empress died, the money problems were gone. She left a well-organised empire to her son Joseph II, which he then reformed into a modern state. This state, despite Napoleon, would grow into the multinational empire of the 19th century.

The Künker Auction at which these coins will be offered can be found here.

And the relevant CoinsWeekly auction preview can be read here.