More and more people struggle to understand why people in the Middle Ages built enormous churches, went on pilgrimages for month and tried to live a lifestyle that is alien to modern hedonists. Especially the saints, who played a decisive role in everyday Christian life, have been suffering from a bad reputation since the Reformation period. And yet, many depictions that can be found on bracteates can only be understood by remembering that medieval people had a close connection to the saints and constantly expected them to intervene in the real life.

This bracteate takes us to Nordhausen of the time between 1160 and 1180. Back then, abbess Bertha was head of the wealthy abbey of the Holy Cross. The abbey was named after a particle of the cross given to the nuns by Otto III around the turn of the millennium. Relics connected to Jesus Christ were the most precious of all treasures. Therefore, Nordhausen became a place of pilgrimage and accumulated such wealth that the nuns started to construct a massive church from 1130 on.

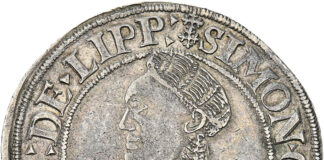

At that time our bracteate was minted. It depicts abbess Bertha kneeling in front of Saint Eustace. His face is turned towards her. He has the martyr’s palm branch in his right hand, in his left hand he holds the cross staff, which often appears as a sign of ecclesiastical power, in this case it may well be interpreted ambiguously as the symbol of the abbey’s most important relic.

The scenery isn’t unusual: one encounters depictions of worldly rulers kneeling in front of saints in numerous churches. Today, we understand these pictures rather symbolically. For Bertha, however, Saint Eustace, to whom the church had originally been consecrated, was the obvious contact person when it came to pushing ahead with the construction of the church. Devout Christians believed that the fact that Otto III had acted in favour of the abbey was due to the influence of this saint. After all, he had the power to lead people – perhaps in a dream – to donate generously to the abbey.

Legends have it repeatedly that saints protected careless construction workers from falling from the building; they showed the architect where the tall and straight trees needed for the roof could be found in the forest, and much more. Therefore, for the abbess managing the construction, there was no better person to ask for help than the saint at whose altar the faithful would pray in a new and magnificent church.

That’s why every ambitious church project needed a powerful protector. And thus, it was not surprising that emperor Otto I put so much emphasis on the fact that the abbey he founded in Magdeburg, and which he wanted to turn into an archdiocese, had a patron with as much power as possible. For this purpose, his connection to the Burgundian king came in handy. He had saved his dominion and in return he received the relics of Saint Maurice and of some of his fellows. The objects had been kept in the abbey of Saint Maurice, which had been founded in 515 and was under Burgundian control at that time.

A warrior saint was obviously a perfect fit for Magdeburg, which was then located at the eastern border of the Holy Roman Empire. In an elaborate procession, the mortal remains were brought to Regensburg, where Otto received them in person. Thietmar of Merseburg reports that they were transferred to Magdeburg, where they were taken “into custody by the unanimously gathered citizens and the rural population”.

You might wonder why some old bones were worthy of such a welcome ceremony, well, this bracteate gives us the answer. The border residents hoped for effective protection: they wanted Saint Maurice to fight for them when it came to defending Magdeburg. And therefore, he is depicted like a margrave, with lance and shield in front of the city wall.

By the way, fighting saints were a rather common thing in medieval times. Saint James, for example, was called the Moor-slayer because people believed they saw him intervene in the Battle of Clavijo on a white horse in 844.

Actually, we don’t have to go back in time that much to find a saint who was ascribed a real-life victory. Otto I had expressed his gratitude to Saint Lawrence, on whose day of remembrance the Battle of Lechfeld against the Hungarians took place, by founding a diocese in Merseburg and consecrating it to him. We are seeing here a bracteate from this very diocese – of course featuring the martyrdom of Saint Lawrence. The necessary relics came probably from Pope John XIII, who legalised the two dioceses of Magdeburg and Merseburg in the context of the Synod of Ravenna.

However, Otto I had taken things too far. His behaviour resulted in the fact that there were no less than three important dioceses at the eastern border of the Holy Roman Empire: Halberstadt, Merseburg and Magdeburg. There were too many of them for their rulers to be able to afford the pomp they considered to be suitable.

The Bishopric of Halberstadt was older than the two dioceses founded by Otto I. It originated from the Carolingian era. However, that wasn’t reason enough. Better ones had to be found if Halberstadt wanted to maintain its importance. It came in quite handy that the bishop of Metz had so many debts that he had to sell some of the relics of Saint Stephen! The bishop of Halberstadt was delighted to pay for them.

Why? Well, in medieval times, the mortal remains of saints were not considered to be objects that people could possess and do with them whatever they considered appropriate. Quite the opposite, relics had their own will and decided for themselves where they wanted to go: the body of Saint James, for example, had itself be carried to Spain in the ship and only revealed itself to hermit Pelayo. Or the corpse of Saint Gebhard of Constance; it refused to be buried in the Konstanz Cathedral by becoming so heavy that nobody was able to move it. At some point, people gave up and buried him, following his wishes, in Petershausen Abbey.

Thus, it had to be Saint Stephen himself who caused the financial problems of the bishops of Metz. The saint preferred to be in Halberstadt than in Metz. Therefore, he became a holy citizen of the city, who was willing to protect its citizens and clergymen.

The fact that Saint Stephen decided to help Halberstadt was exactly the argument the bishop was in need for because Stephen was better than Saint Lawrence of Merseburg! According to the Acts of the Apostles, he had been the first martyr of Christianity and thus outclassed Lawrence who was a deacon of Pope Sixtus II (257–258). Indeed, a little later not Halberstadt but Merseburg was dissolved, only to be founded again under emperor Henry II.

Whereas the saints we’ve mentioned so far are regarded rather as mythical figures today, medieval people knew that all of them had lived and done impressive things, and they were sure that saints lived next to and with them, even though, at least until the 10th century, they expected them mainly to be among clergymen.

An example for this is Saint Martin featured on this bracteate of the bishop of Mainz. We have enough historical evidence to catch a glimpse on the real man. He was born in the first third of the 4th century in Pannonia. Martin was the son of a Roman officer and thus legally bound to serve in the military for 25 years. After his service, he decided to pursue an ecclesiastical career. In 371 he became bishop of Tours. In 397 he died with a reputation for holiness.

Saint Martin quickly became the patron saint of the Merovingians, and when they founded the archbishopric of Mainz, they obviously chose Saint Martin as its patron. Therefore, he also came to the diocese of Erfurt, which had been merged with Mainz in the middle of the 8th century, and that’s where this bracteate was minted.

Heinrich von Harburg (1142–1153) knew to use Saint Martin as an argument, too. The reforming popes would have loved to cut the close connection that united the archbishop of Mainz as imperial vicar with the emperor. However, the Merovingians’ Saint Martin was a worthy opponent of the popes’ Saint Peter.

In general, the knightly princes of the empire were gaining new self-awareness in the High Middle Ages when these bracteates were minted. Each of them could be raised to the rank of a saint. As combative warriors of the Christian God, they set off on armed pilgrimages. One of these knights, Louis III of Thuringia, can be seen here. He died in 1190 in the Third Crusade and was the uncle of a saint. His nephew, Louis IV, was venerated as a saint in Thuringia after he had died in the crusade. But whereas his wife Elizabeth is still one of the most popular saints today, the Church stopped the veneration of a man who died on the crusade of the banished emperor Frederick II.

After all, in addition to the faith in the power of the saints there was obviously also the will of the rules to use this faith to their advantage. Nevertheless: for medieval observers, the depictions on Romanesque bracteates were much more than mere decoration. To those who try to reduce the faith in saints of medieval times to modern opportunism, the message of these splendid bracteates will always remain a mystery.

Find the full preview for the Künker auctions here.

Find out more about the coins of medieval Mainz.

Recently we asked ourselves why the middle ages were so warlike.