Countless stories tell of the Californian gold rush which brought thousands of men to America, the Promised Land. But the gold made only very few rich. The majority died as a result of the exertion during the travel, the hard work and the disappointment when they returned back home, poorer than they had come. Their story should be told here.

Norris, Grieg & Norris. Privately minted gold coin 1849 weighing a “half eagle”, i.e. 5 $. From auction sale Hess-Divo AG 309 (2008), 706.

Coins for California

Certainly, the gold rush has left its mark numismatically, too. The first Californian gold coins were minted by the private company Norris, Grieg & Norris. Thomas H. Norris, Charles Grieg and Hiram A. Norris were engineers, colleagues working together, who had realized that coins were needed in that area as a convenient means of payment. They founded their own company and started coining gold currency on a private basis and with the same fineness as the official 5 $ pieces. They weren’t all too successful, though. When the first year wasn’t over yet, they were already forced to close down their business. Only one single piece, a unique specimen from 1850, hints at further plans.

Much more successful was John Little Moffat, a metallurgist from New York, who offered his services in San Francisco. Together with some friends, he established the Moffat & Co. Company and assayed not only the fineness of the gold consigned but also produced small gold bars of it.

When they proved unsuitable for circulation, he began, in the beginning of August 1849, to issue his own pieces following the model of the official gold coins, which differ only in regard to their legend, SMV (= Standard Mint Value) CALIFORNIA GOLD. Moffat & Co. weren’t the only mint, but the most successful one. Other companies, like Templeton Reid, Cincinnati Mining & Trading Co. Massachusetts & California Co., Miner’s Bank, J. S. Ormsby, to name but a few, manufactured gold coins at a large scale at the beginning of the gold rush that today are highly coveted rarities and obtain maximum prices at auction sales.

Moffat & Company. Octogonal 50 dollar piece from 1851. From auction sale Hess-Divo 323 (2013), 887.

The happy times, however, were about to come to an end finally. On 30th September 1850, the Congress authorized the treasury’s secretary to establish an authority for assaying as well as buying gold. Because Moffat & Co. were quite successful in business, they were brought in – and they got company: Augustus Humbert was being sent, a master watchmaker from New York, whose job it was to check on them. He was the one responsible for the first official currency made of Californian gold, octagonal ingots, whose reverse had a striking resemblance to the mechanically engraved watch cases of those days.

These ingots and the ‘ordinary’ US coins could circulate simultaneously, but the former were no official means of payment. The problem of these specimens was that they had too great a weight. Compared with the official 10 and 20 $ dollar coins below weight, they contained much more gold – which was a nuisance to the banks who couldn’t get rid of their own currency anymore. Consequently, they took revenge by exchanging the ingot with the too big intrinsic value with 3 % discount only. That, in turn, made the ingots become much less popular; Moffat & Co. was forced to produce their old 10 and 20 $ dollar coins instead again, this time on behalf of the US government.

United States Assay Office 20 $ 1853. From auction sale Künker 109 (2006), 1400.

On 14th February 1852, John Moffat was fed up with gold and coins. He decided to engage in the development of a diving bell and hence separated from Moffat & Co. As a result, his company was finally converted into an official assay office that issued coins by order of the United States.

Already on 14th December 1853, however, the official assay office already closed down, the Congress having decided as early as 1852 to establish a mint of its own in San Francisco which was scheduled to start working in 1854. That, on the other hand, proved to be impossible since the minerals required for alloying hadn’t arrived in time in San Francisco.

Kellogg & Company. 20 dollar piece 1854. From auction sale Hess-Divo 309 (2008), 707.

So the company Kellogg & Co., founded by a former Moffat & Co. employee and the official assay office, stepped into the breach. It coined as long as 1855, when the San Francisco Mint finally produced enough coins to cover the requirements.

As late as 1854, gold coins worth $4,084,207 with the mint mark S for San Francisco were manufactured. The number was to increase year after year. Soon, the brick building of the first mint became too small.

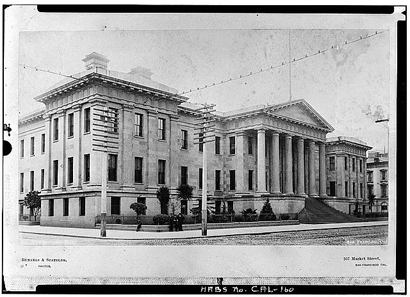

Building of the second San Francisco Mint, inaugurated in 1874.

A new and stately factory, whose design was based on a Greek temple, was built in 1874.

Privately coined 1/2 dollar piece 1857. From auction sale Hess-Divo 323 (2013), 891.

Despite the official mint, there remained a small niche for private coining. After all, California was small on change and so the government allowed gold smiths to produce 1/4 and 1/2 dollar coins, which today are relatively easy to come by in the coin trade. They continued to circulate, even though the so-called “Private Coinages Act” from 1862 prohibited any private coining.

The end of the gold rush

Already in 1855, it was foreseeable that the individual gold prospector had no chance anymore to make a fortune in California. Hence, the hysteria seized and everything went back to normal. Mining companies were founded, with large capital brought in. A great number of former gold diggers got themselves a new job there. Lawyers and doctors remembered their old profession in which they started to work again in the promising and aspiring new state. Wives and families followed the successful men. Justice, law and order arrived, too. There were hardly any marks of this episode still detectable in 1860. What good did the gold rush bring after all? Well, it brought gold worth 639 million dollars as well as a new state being developed speedily. In addition, the new state was quite conveniently situated, geographically speaking. With California the USA had a base likewise on the western side of the continent, thanks to the gold rush. The civilization, as it were, was able to gradually expand until even the remotest part of America was peopled by white settlers.

Likewise a new path across the Pacific Ocean had opened up for the USA. With San Francisco the United States possessed a port much better suited for the trade with Asia than the traditional European ports. It seems only logical that President Fillmore sent an American fleet as early as 1852 with the goal to force Japan to engage in trade.

How about Sutter?

What has become of Sutter? He had filed a lawsuit against the Federal Government in Washington and against 17,221 people for illegal settlement. The US Land Commission judged in favor of Sutter in 1855, but when Sutter was on his way to Washington to let the verdict be confirmed by the Supreme Court the court building was being burnt to the ground and all record destroyed. The mob, outraged by the verdict, marched onto Sutter’s plantations and battered one son to death; the other one committed suicide, from shame of not being able to stop the disaster. Sutter continued to fight for his right, but the War of Secession intervened in 1861.

After the war over, Sutter’s once huge fortune had been massively reduced, but that didn’t make Sutter give up. He went to Washington to assort rights but his bill was adjourned again and again. When a senator, a friend of Sutter’s, visited the then 77 year-old to tell him that his compensation was sure to be granted in the next Congress’ meeting, he found Sutter dead. The deceased owned only just 22 cents.

The two previous episodes you can read again here: part I and part II.