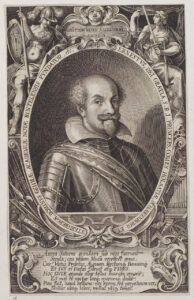

On 28 January 2021 auction house Künker offers a small series of coins minted by the rulers of the House of Schaumburg in auction 346. The highlight is certainly a splendid 10fold ducat by Ernst III, Count of Schaumburg and Holstein-Pinneberg. Despite his titles, Ernst III did not consider himself above devoting his time to the extraction of coal and sandstone. This made him so rich that he could afford to mint magnificent coins like the piece offered at Künker.

A Renaissance Prince with a Talent for Business

Ernst III was born, as the Schaumburg court historian Cyriacus Spangenberg tells us, on 24 September 1569 between 6 and 7 a.m. At that time, people probably didn’t make a fuss about his birth. Ernst was the youngest son, and his father already had four sons from his first marriage at the time of Ernst’s birth. Thus, Ernst’s chances of becoming a ruler were rather poor.

That’s why his parents sent him to the University of Helmstedt to study law already at the age of 15. This was common for a young man who aspired a career in the service of the emperor, important princes or in the administration of the Holy Roman Empire. The education included a subsequent “Grand Tour”, during which the young man learned several languages and courtly behavior. In addition, he had to broaden his network, certainly in terms of politics, but perhaps also regarding economic relations.

Thus, Ernst III did not only travel to Italy and to the court of the emperor, he also went to the Netherlands, one of the most important customers of sandstone, which his home county was rich in. In the Netherlands, certainly he did not only familiarize himself with the latest artistic developments, as art historians used to bring up again and again, but also with a system called cameralism. In the era of early absolutism, this term described an economic policy that was meant to enable a ruler to cover the costs of representation and a standing army by fostering several sources of income.

Ernst III seems to have shown promising potential because Landgrave Maurice of Hesse-Kassel agreed to give him his sister as his wife. In 1597, Ernst III married Hedwig of Hesse-Kassel.

At that time, nobody knew that Ernst III was to inherit his brother’s estate in July 1602. For Ernst, it was a stroke of luck that the 16-year-old son of Count Adolf XIV died shortly before his father, with the result that Ernst surprisingly inherited the Counties of Schaumburg and Holstein-Pinneberg.

And that wasn’t the only surprise: Ernst made use of what he had learned during his Grand Tour. He optimized the most important branches of Schaumburg’s economy. As early as on 19 October 1601, he adopted his first, well thought-out decree for the reorganization of the coal mines. And more decrees were to come.

Coal Mining

Since the Middle Ages, a legal conviction prevailed in the German States according to which whatever lies under the ground was the property of the ruler of the territory. And that did not only apply to silver and gold, but also to coal.

At the beginning of early modern times, coal usually wasn’t used for heating – and the same was true for the alternative product charcoal. It was too precious for that. Thanks to its long-lasting, even heat, coal played a decisive role in the ore extraction industry. Coal was essential for melting gold, silver and iron. In other words: to a clever prince, a coal mine on his own territory was just as valuable as silver mines.

And Ernst made sure that coal mining was professionalized in his counties. Under his rule, more than 300 men extracted about 30,000 tons of coal per year. A major part of it was delivered to the silver mines in Brunswick. Bremen was an important customer, too.

Sandstone from Bückeberg

Ernst made use of both coal and sandstone extracted from Bückeberg. We should not forget that there was a construction boom in Europe at that time. To make most of his sandstone, Ernst III installed a port on the Weser river near Petershagen in 1607, from where sandstone was shipped to Bremen. From Bremen, it was exported to the Netherlands, the Nordic countries, the Baltic states and Switzerland. There it was known as “Bremer Stein” (Bremen stone) and “Grauwerk” (grey stone).

Thanks to large profits from the coal and stone industry, Ernst III rehabilitated his counties. He was soon considered so wealthy that Emperor Ferdinand II approached him for a loan of 100,000 guldens. Ernst agreed, and in 1619 he was granted the non-inheritable title of prince and the right to found his own university.

Buildings Commissioned by Ernst III

We don’t have to mention all the buildings that Ernst III financed thanks to his income from the coal mines and the quarries. But we would like to recall Bückeburg palace, the town church of Bückeburg and the princely mausoleum in Stadthagen, one of the main works of the Mannerist sculptor Adriaen de Vries.

The Division of the County of Holstein-Schauenburg

On 17 January 1622, Ernst III died childless. A cousin inherited the estate. In 1642, his line became extinct too. Thus, the counties of Holstein-Schauenburg were split up. Holstein-Pinneberg was shared between the King of Denmark and the Duke of Schleswig-Holstein-Gottorf. The County of Schaumburg was given to Philip I of Lippe, except for a small part of it that was inherited by the Landgrave of Hesse-Kassel. This was the end of the story of Holstein-Schauenburg, and the chapter of Schaumburg-Lippe began.

The Connection Between Schleswig-Holstein and Schaumburg

Whether it be Schleswig-Holstein or the administrative district of Schaumburg, traces of the Schauenburg dynasty can be found to this day, and this does not only apply to the townscape. The stylized leaf of a nettle (“nesselblatt”) is a heraldic connection between the federal state in the north and the administrative district in Lower Saxony. This very leaf is depicted on the 10fold ducat of Count Ernst III of Holstein-Schauenburg.

Here you can read a comprehensive auction preview.

You can browse the complete auction catalogue on the Künker website.