Batalha means battle. The word’s meaning instantly shows in its English translation. A town does not just get a name like that for being the scene of “a” battle, only for being the scene of “the” battle in Portuguese history. What the Battle of Hastings is for England, the much less well-known Battle of Aljubarrota is for Batalha. To the Portuguese, however, it is just as important as the Battle of Hastings to the British.

Tuesday, 14 April 2015 – Batalha, Tomar and Fatima

We set off at 8.30 am since we had planned a very tight schedule for the day: Batalha, Tomar and Fatima, two UNESCO World Heritage cities and one of the world’s most famous pilgrimage sites were really ambitious for just a few hours.

First we took to the highway. Unfortunately I used my map for navigation instead of the road signs so that the exit we took, though geographically closer to Batalha, led to our destination by passing many tiny villages and hardly any road signs at all. At one point I was convinced that we were totally lost until the gigantic cathedral suddenly popped up in front of us, towering above everything else.

Batalha is the place where the Portuguese fought “their” battle, the Battle of Aljubarotta, the battle which is the foundation of their national pride, the battle which separates them from Spain.

In October 1383 King Fernando I of Portugal died. He left behind only a daughter and no son, and that daughter had been married by her father to Juan I of Castile of all people. According to medieval legal practice the crown should have belonged to their common heir.

The Portuguese were not at all happy about that. They did not want to be swallowed up by Castile. And luckily there was a pretender that everybody could agree on: Joao, grandmaster of the Order of Aviz, and illegitimate son of Pedro I of Portugal, father of the deceased Fernando.

He soon found many supporters in Lisbon and among the gentry. With Nuno Alvares Pereira at his side, a gifted strategist who relied on English defence strategies to fend off the Castilians repeatedly, he managed to fight off the Spanish attacks for several years, a period that is remembered in Portuguese history as the Interregnum.

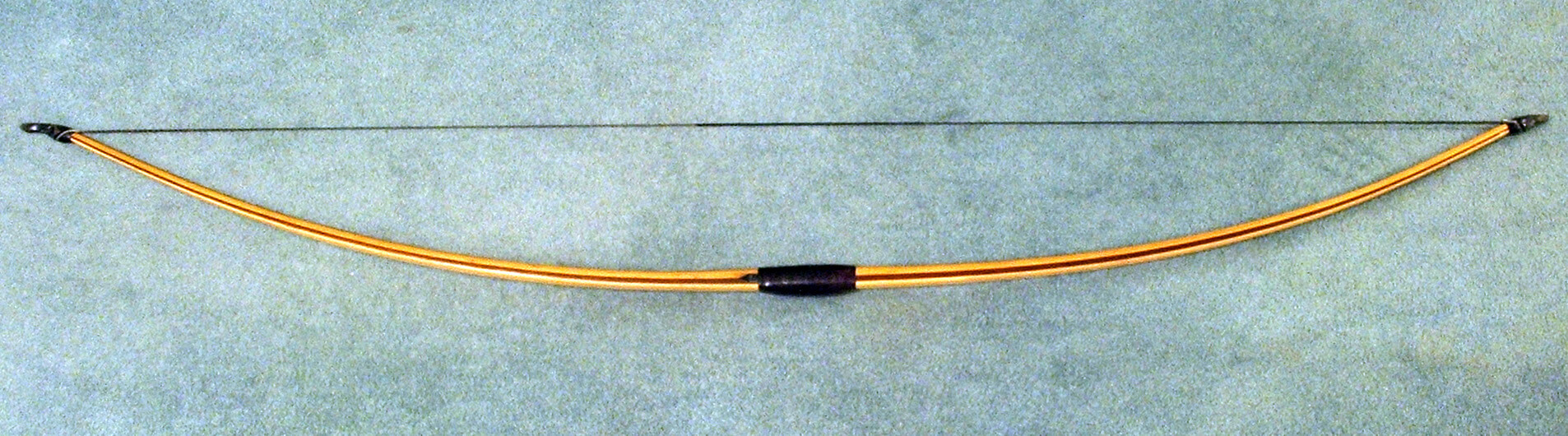

An alliance with England turned out to be the decisive factor. It brought Joao exactly 100 of the legendary longbow archers who had erased the elite of the French knighthood not even a generation ago. So Joao dared proclaim himself King of Portugal on 6 April 1385, causing an immediate counterstrike by Juan of Castile. He is said to have led 31,000 men against Portugal, among them countless French knights. The Portuguese could only counter this with 6,500 men – and that is including the English archers. Even though these numbers would most likely not pass an examination by a modern statistician, they still show that the Castilians must have far outnumbered the Portuguese.

The opposed forces met on 14 August 1385. Once again the longbow archers smashed the knights who had been confident of victory. More than 5,000 Castilians are said to have died in the Battle of Aljubarrota. Although Juan of Castile still did not drop his claims after the defeat, Joao’s rule was secured. From then on the House of Aviz ruled over the country.

Joao married an Englishwoman, Philippa of Lancaster, a sister of the English King. The marriage was part of the Treaty of Windsor from 1386, the oldest still valid diplomatic treaty in Europe.

And where the standard of general Nuno Alvares Pereira had been raised during the battle, a small chapel was erected. It was given to the Dominicans in 1388, together with enough funds from the royal treasury to build a fantastic, magnificent monastery, designed to serve as tomb for the dynasty.

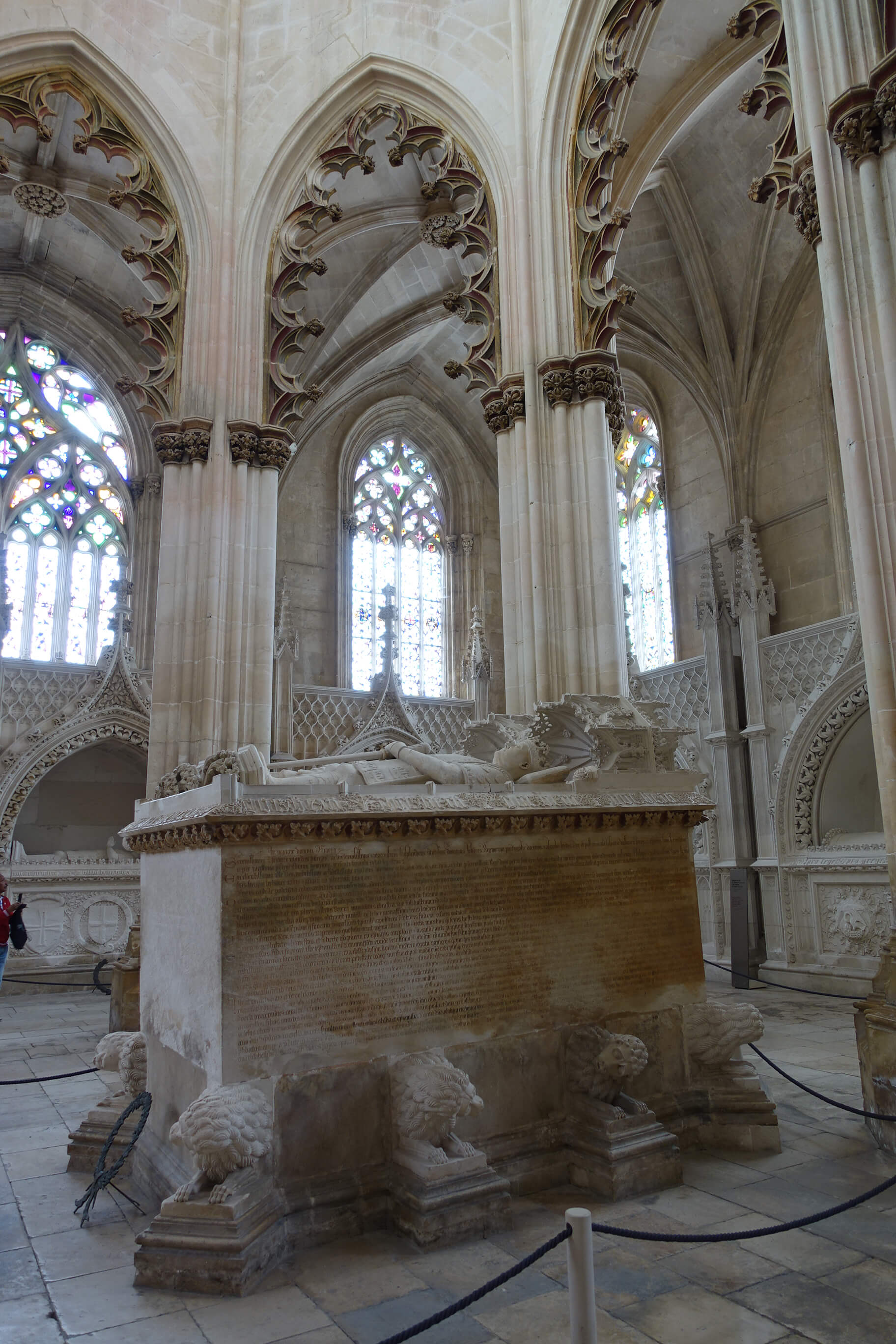

On entering the church, the rich architecture can be somewhat overwhelming. No wonder it took more than a hundred years to build the monastery. And even when construction works stopped in 1517, the impressive complex still had not been completed.

Located right next to the entrance is the Founder’s Chapel with the sarcophagus holding the bones of Joao I and his spouse Philippa in its centre.

Buried next to the king and queen are their children, among them famous Henry the Navigator.

The splendid cloister which can be entered from the church will teach any photographer a lesson in stoicism. The problem is not that there are too many people around. Visitors were rather trickling in. Still, there was always at least one visitor in the way of you getting a picture of the cloister without any people in it. It seems that today not only those with a camera are taking pictures but also the thousands of mobile phone users who urgently need pictures to share on various social networks. A wish I can empathise with (kind of).

But there is a point when you have a really hard time keeping your composure. That point is reached when phone users not only take pictures right in the middle of the cloister but deem it necessary to remain there while sharing it with his friends and also to remain there while waiting for their friends to like the picture. In the meantime, dozens of other photographers, who would also like to take a picture but without them in it, start queuing behind them.

Well, I guess such moments teach us how differently the importance of the individual can be perceived. The sense of self-importance of the selfie-producer lies far from what all the other photographers, who cannot take their pictures because he is in the way, think of him.

The chapter house today serves as the national memorial site for the dead soldiers of WWI, which makes it not unlikely that you will run into one or the other patrolling soldier in the cloister.

This also explains what at first sight seems like a fairly misplaced exhibition on the Portuguese military in the refectory.

And when you think you have seen it all, signposts lead you to the Capelas Imperfeitas or Imperfect Chapels. At first we did not quite know what to expect here but the second we stepped into the annexe, the sight took our breath away. A beautiful, elegant building, perfectly executed and with great attention to detail. But the roof has been missing since the 16th century!

Dom Duarte, son of Joao I, intended to build his own burial chapel. Only he died a little too early, in 1438. Even though his successors dutifully continued with the construction for a while, they never completed it.

This chapel, built with the greatest skill, artistry and sophistication, but missing something crucial – the roof – is the perfect symbol of Portugal. You could regard it as a symbol for the global ambitions of a nation that was the catalyst for so many developments but never really harvested the fruits of its seed. And what a relief that Portugal never gave birth to some Viollet-le-Duc, who could mutilate such a monumental imperfection with a flat and unsophisticated 19th century addition.

As yet Batalha fortunately shows very little traces of being a UNESCO World Heritage Site. Still missing are the streets with souvenir shops, overpriced cafés and cheap restaurants with bad food. The café just opposite the cathedral, where we had a sandwich, was mainly frequented by locals – despite its perfect location with a superb view of the cathedral. And the owner’s most profitable guests that day were not the tourists but the flock of schools kids, all of which bought ice cream and a bunch of sweets …

Anyway, we did not stay long but drove on to Tomar, the best preserved original monastery of the Knights Templar still in existence today. Quick reminder:

Philip IV of France had large debts. The Templars had money. So the king used his power to condemn the Templars as heretics and sodomites, and confiscated their fortune in France.

In Portugal one had a quite different take on the matter as the Reconquista was still in full swing. The Portuguese hoped for active support in the fight against the Muslims. If the order did not answer to the headquarters in Paris, even better. So King Dinis sent a messenger to the Papal court, which at the time resided in Avignon.

After more than a year, the plan to get a papal bull issued by John XXII (yes, the same Pope who fought Louis the Bavarian so fiercely) succeeded. In this bull John XXII declared that the possession and property of the Knights Templar was to be transferred to the newly founded Order of Christ. The new order should adopt the rules of the Order of Calatrava, and that was that, more or less. The Knights Templar had become the Order of Christ.

The king pretty much used the order for his purposes at will. Time and again a son or brother would be instated in an administrative position at the order so that its abundant resources could contribute to the expansion of the Portuguese empire. Not to forget that the Pope had trusted the order with the proselytization of the new territories.

In 1496 the knights of the order received the papal dispensation from celibacy, 1505 from poverty. These changes meant that new, secular members joined the order. Among the most famous are Bartolomeu Diaz, Vasco da Gama, Pedro Alvares Cabral and the German Martin Behaim from Nuremberg.

No wonder Manuel I could not think of a better coat of arms to feature on his coins – made of African gold from his newly conquered territories – than the cross of the Order of Christ.

Tomar became the headquarters of the Templars and later the Order of Christ in Portugal. Although construction works for the original castle had begun already in the 12th century, most of the buildings you can see today date back to the rule of Manuel I, who as a prince had been appointed administrator of the order, during Portugal’s Golden Age.

Today Tomar is a textbook example of the so-called Manueline style, a variation of the late-Gothic style, which became a trademark of Portugal under King Manuel I. The style combines ornamental elements from seafaring, such as knots, ropes or the armillary sphere, and the sea world, such as seaweed and shells, with other, more unusual forms, such as oak leaves, poppy seed capsules, and thistles, all of which occur in abundant combinations and are worked with the greatest attention to detail. The style is unique and, once seen, unforgettable.

Another highlight awaits admirers of Romanesque art: The church, built in the second half of the 12th century, was modelled on the example of the Holy Sepulchre in Jerusalem, a hexadecagonal (that makes 16 corners in case you were wondering) building with an embedded octagonal central room. It is the best preserved example of such a ground plan in all of Europe.

In Tomar we were moving between two tourist parties. An art form, really. Quickly into the one room as soon as the first group had disappeared and quickly out again before the next one advanced. Not exactly what I would call relaxing. Unfortunately the Templars make a very nice stop on each travel itinerary, which is why all-inclusive tours apparently cannot afford to do without them.

There is, however, a lot that could still be done about Tomar’s infrastructure. We simply were not able to locate a café worth visiting anywhere nearby – and no one seemed willing to make use of the beautiful, cool and shady garden in front of the castle …

So we got in our car and moved on to Fatima, knowing that pilgrimage sites usually care for the pilgrims’ physical well-being as much as for their souls’.

Fatima is built around the legend of a Marian apparition, seen by three local children on 13 May 1917 while herding their sheep. On the 13th day of every month Maria showed herself to Lucia, Jacinat, and Francisco, a phenomenon that soon attracted a large number of believers. On 13 October 1917 several ten thousand pilgrims witnessed the “Miracle of the Sun”, described by an eye witness as follows: “The sun, at one moment surrounded with scarlet flame, at another aureoled in yellow and deep purple, seemed to be in an exceedingly swift and whirling movement, at times appearing to be loosened from the sky and to be approaching the earth, strongly radiating heat.” (Translation of quote taken from here.)

The Madonna became a darling of the press because she had trusted the three children with three secrets, one of which was not meant to be published until 1960. Even though the first two had not been very original, the fact that the Vatican was holding back the third secret caused a lot of speculation. It was not until 2000 that Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger, in his function as Prefect of the Sacred Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith, decided to discover the secret to the public. It must have been a great disappointment for the newspapers that the somewhat confused text could not be summed up in one lurid headline.

Today Fatima, like so many other Catholic pilgrimage sites, oscillates between real piety, kitsch, and commerce.

It starts with Madonnas made of plastic and it ends with the Hotel Alleluja, which prides itself with having won the Travellers’ Choice Award 2015 and having a buffet that will satisfy even the hungriest pilgrim.

As Fatima’s old church was being renovated with great noise, we ended up at the new Church of the Santissima Trindaded (Church of the Holy Trinity), currently the largest new-built church in the 21st century. Round about 9,000 people can attend a mass while being seated. And all of them can see the altar as there are no pillars in the way.

Between the old and the new church lies the world’s biggest church forecourt. And by necessity so. On 13 October 2007 alone, 250,000 believers came together in this place to celebrate the 90th anniversary of the third prophecy of Fatima.

The matter got too holy for our taste. By now it had also started raining and we had seen plenty that day already. We returned to our hotel in Batalha.

Our next episode shows Portugal as highly controversial: In Alcobaca we will hear a love story that makes Romeo and Juliet seem like yesterday’s news. And in Peniche we are confronted with the long and troubling years of dictatorship under Salazar.

Here you will find all episodes of our series “Global Power Portugal”.