History is not an accurate science. It is based on sources and the interpretation of these sources is in the hands of those who use them. That is why history in the hands of nationalistic states is so dangerous. Governments have a tendency to monopolise history and use it as a means to their ends. And sometimes they are successful enough to change the face of history even after their own downfall. Guimaraes makes a good example of this, a town from the High Middle Ages whose medieval edifices are in surprisingly good condition.

Saturday, 18 April 2015 – Guimaraes, Marco de Canaveses and Portugal today

It was raining when we got up. It was raining when we started driving. And it was raining when we arrived in Marco de Canaveses. You have never heard of Marco de Canaveses? Don’t worry about it. You did not overlook a major attraction in the Baedeker. There is, strictly speaking, just one attraction in Marco de Canaveses: Café Pianissimo. It does not derive its importance from having any Michelin stars but because it is owned by a friend of ours. Adao Pedro Pinto de Jesus, the best man at UBS in Schaffhausen, the best waiter – apart from his brother Paolo of course – at Café Vordergasse, the man who can turn the grumpiest sourpuss into a happy fella in a second.

We have known Pedro for many, many years. He came to Switzerland because there was (and is) not enough work in Portugal. 10 million Portuguese live in Portugal. Plus a good 4 million who live abroad. And that is without counting the Brazilians descendants.

Just like many other Portuguese, Pedro comes from a big family. Since his mother lost her husband early, she was not able to financially support any expensive job training of her sons. So Pedro moved to Switzerland, worked as a waiter, watched and learned. Until a UBS manager recognised his talent for dealing with people and asked Pedro to work for him. As a customer consultant at the bank, Pedro was hugely successful. And then he left again. It was not easy working with colleagues who could not stand the fact that a Portuguese without education scored better results than all the Swiss employees with their Swiss high school diplomas and university degrees.

Pedro returned home, to Marco de Canaveses. There he opened a café, just as special as Café Vordergasse in Schaffhausen. And the success was incredible. He does not just make enough money to support himself, he also provides work for several people.

So. We wanted to visit Pedro. Which turned out to be harder than expected. With our typically German-Swiss arrogance, we had expected that a town we had never heard of before could not be more than a handful of houses scattered around a town centre. And how wrong we were. Marco de Canaveses is a local hub with aggressive traffic, too few parking spots, and far too many one-way-streets. After driving round in circles for a good hour, both of us were seriously annoyed and had pretty much lost hope of ever finding the Pianissimo. And again we were wrong. The first person we asked knew the Pianissimo and, not speaking English, showed us the way with many gestures. It was not far. We had parked just 300 meters away from it.

There was a big hurray when we showed up. We had not been able to give the exact day of our visit in advance, but although we had announced our visit loudly, neither Pedro, nor his brother Paolo, who is still our favourite waiter at Café Vordergasse, had believed us. So there we were and immediately we were invited to celebrate Paolo’s 50th birthday the following day. Of course we promised to be there before we drove on to the nearby Guimaraes, where we would spend two nights in a pousada that might be the most beautiful in all of Portugal.

Should you ever stay there, you must know that the pousada is not that easy to find. At first, it appears visibly exposed on a mountain. The problem is that there is but one street leading up to it. And to get to this street, you need to trust the signs which seem to obviously lead you astray. The first time we circled the town we refused to believe that the sign, which sent us off to an obscure-looking side road at a 30 degree angle. And now we paid for our disbelief with driving circles after circles around the city. It took more than an hour until we accidentally came across the turn that led to the pousada again.

We had gotten along extremely well with the manager of the last pousada. When he heard that we were on the way to Guimaraes, he said he would call a friend who was the manager there. Was it the phone call or did we just get lucky? I don’t know, but the room we stayed in was beautiful with a fantastic view over the whole city of Guimaraes. The only downside: it was still raining. And even worse, we still had not found a shop that sold umbrellas.

It was raining when we visited the town centre of Guimaraes. We jumped from eaves to eaves and still had water dripping down into our collars. What to do? Go to a museum at once, of course!

The museum in Guimaraes is more than just a museum. It is almost something like a national pilgrimage site because several great national treasures are kept here, like the statue of the Madonna of Oliveira, who, so Joao I believed, gave the Portuguese the victory of Aljubarotta.

We have already reported about this in part 9 of the travel diary. The cathedral in Batalha was built in memory of the decisive battle, in which Joao I, an illegitimate son of Fernando I, won a victory against the Spanish husband of the deceased king’s legitimate daughter. And so the battle decided that Portugal would remain Portugal and not become annexed to Spain. (The uprisings, which ended the Spanish hegemony in Portugal in 1640 and reinstated the House of Braganza as ruling power after more than 50 years, on the other hand, are a topic that is generally much less addressed in Portugal’s touristic spots.)

Here you can read the story of the Battle of Aljubarotta again.

Anyhow, the museum in Guimaraes does not only display the statue of the Virgin Mary, but also a contemporary painting of Joao I, the first painting of a Portuguese ruler ever produced.

Another national relic is on display here as well, the gambeson worn by Joao I in the Battle of Aljubarrota. Yes, I admit it, I also heard this word for the first time here. A gambeson is something like a textile armour. A sturdy piece of clothing made of several layers of linen which are padded with cloth. A gambeson is worn underneath the metal armour and serves to protect its wearer from sword hits. It does not, however, offer protection from stabs. That is what chain mails are for.

It was still raining when we left the museum. We decided that the driest place we could be in this weather was our room and that tomorrow was always another day.

Sunday, 19 April 2015 – Guimaraes and the Douro Valley

The next day did come, and what a day! Dazzling sunshine greeted us when we got out of bed. We made plans to see the landmarks which make Guimaraes so famous: the Castle of Dom Henrique, the baptistery of Afonso Henrique, and the Paco Ducal.

Dom Henrique, better known as Henry of Burgundy, in his time the first count of Portugal, died in 1112. Under his rule Guimaraes was the capital and it stayed that way under his son Afonso Henrique too. At first. In 1143, he moved and Coimbra became the new capital.

What do most 12th-century castles in Germany look like? Right, unless they were restored in the 19th century, they are ruins. Which is exactly what the Castle of Guimaraes would be if Salazar had not recognised it as a monument of the birth of the Portuguese nation, whose maintenance was essential. So the castle was rebuilt.

Just like the nearby baptistery.

This is what the Paco Ducal, the “Ducal Palace”, looked like before Salazar took care of it.

The reconstruction works began in 1937, four years after the seizure of power by Salazar. In 1960 the “medieval” palace was completed.

It served as a museum – and as Salazar’s residence when he travelled and inspected the north of the country. There is, I hope, no need to emphasise what propagandistic benefit Salazar gained from establishing such a close connection between himself and the founder of Portugal.

What I do need to say, however, is that alarmingly few visitors are aware of the fact that the halls they are walking are not in an original 15th-century condition but staged by a dictator. Even the otherwise very well researched Dumont art travel guide failed to mention the parts that were newly created and treated the complex of buildings as if it had sprung straight from the Middle Ages into our 21st century as a whole.

But there was little time left for us. After all we were invited to Paolo’s 50th birthday in Marco de Canaveses in the afternoon. A surprise awaited us right next to the restaurant: there is a fantastic excavation site near Marco de Canaveses.

Although Tongobriga is listed as a “Monumento Nacional”, it is far less well-known than, for example, Conimbriga. Tongobriga is a Celto-Roman settlement that was already known to the geographer Strabo. Since the 1980s, excavations have been taking place in the area, which is roughly the size of 75 acres.

As I said, the restaurant was just next to the excavation. It is not always open. In fact, it is only open upon prior reservation. And we had made a reservation. Well, not we, but Paolo and his birthday guests.

Only close family and friends were invited. Paolo’s mother, Lola’s parents, his many brothers with their wives and a host of cousins. All in all perhaps 30 people. And the two of us. You could have expected us to be pretty isolated, what with our Portuguese being practically non-existent. But more than half of the family had already lived abroad, worked abroad, or lived in other countries with their parents. So almost everybody spoke German well and welcomed us with a heartfelt friendliness that made us feel more than ashamed about the Swiss popular initiative “against mass immigration”. And don’t think Germany is any better!

There we were, being spoilt with Portuguese delicacies. First, tons of starters. For the main course, there was – among others – traditional bacalhau, a speciality of which every Portuguese consumes an average of 15 kg a year. Bacalhau is basically just cod that is preserved in a special manner. After being rubbed with sea salt, it is dried 150 days by wind and sun, give or take. Although, strictly speaking, the largest share of cod today comes from Norway, not from Portugal, but that is a different story.

I don’t know about the others, but we had a lovely evening and returned to our hotel much later than intended. Had it been up to Pedro, we obviously would not have driven home at all, but spent the night in one of the many guest rooms at his huge house. And even finding a pyjama, he promised, should not prove impossible!

So much about Portuguese hospitality.

Monday, 20 April 2015 – Braga

The next day, we did not set off quite as early as we had planned. Our destination was Braga, a city praised by all travel guides for its stunning beauty. But first we had our hands full with finding a parking spot in this beautiful Braga. Most spots were already taken and the city not exactly what you would call manageable or easy to find your way around.

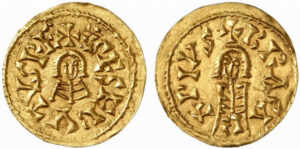

Braga’s fate resembles that of most Portuguese cities. First settled during the Megalithic Age, it became one of the centres of the Castro culture before the Romans conquered the territory. Then Augustus founded the colony Bracara Augusta and named it after the local tribe of the Bracari, which lends its name to Braga until this day. In the Migration Period the Suebi came to Portugal. They founded their kingdom in the north and made Braga its capital. In 584 the Visigoths took over. That Braga remained an important centre is indicated by the fact that coins were being minted here. Not to forget the two synods that were held in Braga with the purpose of drawing clear distinctions between the Christian teachings and those of Arianism and Priscillianism. And since Braga used to be the centre of the church in this time, later arch bishops continued to insist on a primacy in Portugal (which somewhat explains the lavish baroque decoration of the cathedral).

In the 8th century, the territory was conquered by Islamic troops. Still, it remained contested until it was reconquered by Ferdinand of Leon and Castile in 1040. For a short period of time, it became one of the residences of the Portuguese court until it lost its position first to Guimaraes, later to cities even further in the south.

Due to its location in the heartland, Braga did not profit as much as other cities from the Portuguese conquests. Still, it was a thriving commercial town, whose baroque architecture has survived the developments of the 19th century because it was on the periphery of change. This fact is being exploited by the tourist industry today. Braga is celebrated as the “city of churches”. And indeed, the city has more than enough of them.

If you have grown up with post-Reformation Protestantism, the weight of counter-Reformation baroque can feel almost suffocating. Each and every corner decorated with gold. And because the 19th century did not have the means to rid the churches of their baroque costumes and restyle them in the fashion of the time, visitors get a good idea of the pomp that came with giving Romanesque churches a baroque look. The organ in the Braga cathedral alone is worth the journey, even though I cannot say that I liked it.

So we took a stroll around Braga. After the third church, we gave up on our plan to see all of them; after two hours, we decided that Braga was a great city but not really a city we liked. Plus, we still had to get to Porto today to return our rental car. And in case we passed by the famous pilgrimage church Bom Jesus do Monte (you probably know it, it is the one on the mountain with the many steps), we wanted to take a look as well.

To cut a long story short, we did not pass by the church. Curious road signs combined with aggressive traffic convinced us that we had seen enough churches for today anyway. So we drove to the airport in Porto, returned the car and arrived at our hotel in Porto exactly 40 minutes after we had pulled up to the rental-car office. Cheers to Europcar!

Here you will find all episodes of our series “Global Power Portugal”.