by Ursula Kampmann

It is rather unspectacular what can be seen on our German 1, 2 and 5 Cent coins: a simple oak branch with four big leaves and another small one, a twig on the left with two acorns – boring, one might say.

An oak branch as the motive of our 1, 2 and 5 Cent coins.

By that, however, he would compromise himself since the oak symbol is very old and closely connected with Germany, its national identity and its democracy for nearly 300 years.

Sacred oak of Zeus in Dodona / Epirus (Northern Greece); of course, it is a new planting where archaeologists suppose the tree originally was located.

In ancient Greece, the oak was regarded the tree. The word drys (= oak) originally denominated all trees. Being the tree the oak naturally stretched quite far. Never stopping to provide wood for building ships, single specimens and, for that matter, groves were scared. Anyone who dared to set his hand to such a sacred tree was executed although some cities later settled for a considerable fine.

Classical Greek belief had integrated many vegetation deities of previous civilisations.

Thessalian League. Victoriatus, 2nd-1st cent. B. C. Head of bearded Zeus with oak crown r. Rev. Athena Itonia advancing r. 6.04 g. SNG Oxford 3800. From auction sale MAG 88 (1999), 162.

The veneration of trees was part of the urban ritual with the oak usually attributed to Zeus. After all, it was the oak most often hit by lightning – in those days it was believed that the father of the gods expressed his love with that sign. There was generally a close connection between trees and people in the 5th cent. B. C. Not only were some humans transformed into a tree (one might think of Philemon and Baucis or Daphne), that process was well-known vice versa as well. A legend says that man was not – as commonly believed and written by Hesiod – made of clay but descended from the oak.

Taranis with wheel and thunderbolt. Le Chatelet Gourzon Haute Marne / Wikipedia.

Sacred trees were known not just to the Greeks but to the Romans and, of course, to the Celts and the Germanic peoples. The Celtic protector of the oak was called Taranis derived from taran (= to thunder). He was the god of battle as well as the sky. His tree was cared for by druids, the Celtic priests, whose name may be translated as “oak knowledgeable”. According to tradition, they sacrificed two white bulls under an oak every sixth day after new moon. One druid, clad in white garments, climbed up into the branches to cut mistletoe growing on the tree with a sickle while his colleagues were ready to collect the mistletoe in a white cloth. Pliny (XVI, 249 et seq.) writes that nothing was more holy to the Celts than those mistletoes that grow on oaks. It was strictly prohibited to fell oaks with mistletoes on them.

The Romans regarded the oak as the tree typical for the North and associated the tree with the wild vastness of the unconquered Germania. Tacitus in his Germania already attested the country “gloomy forests or nasty marshes”; he was followed by Pliny in his Naturalis Historia (XVI, 5 et seq.). He describes Germania as a country covered up to the seashore with oak forests allowing no sunbeam to touch the chilly ground. The Germanic oaks in the Hercynian forest came into being along with the world and were untouched for centuries. They excelled all other natural miracles with their tremendous size, their outlandish appearance and their fateful immortality.

((Fig. 5 – The Battle of the Teutoburg Forest. Drawing of Crown Prince Frederick III. Clearly visible are the oaks under which the Prussian Prince let the battle take place.))

Of course, the Germanic peoples had their sacred groves, too. If Tacitus (II, 12) is to believed Arminius concentrated his troops in a grove sacred to Thor before he defeated Varus. The booty was stored in a sacred grove as well. The Annals tell us that Germanicus visited the battle field in the Teutoburg Forest in A. D. 15 and came across the sculls of the soldiers killed in battle hanging from the trees.

Hence, for the Romans the oak was connected with the rebellious peoples of the North. Resistance was something Rome could not tolerate. The renitent comrades-in-arms of the independence movement had to be crushed. Those who were wiped out were the “oak knowledgeable”, the druids. The Romans left the oaks but the veneration was not quite the same after the victory of Christianity. The Christians preferred the martyrs’ palm; the oak became a nuisance to the rigid church fathers. The places where the believers were close to the idyllic vegetation deities had to disappear. That was a matter for the boss. The Second Council of Arles (A. D. 452) issued the following edict: “When in a diocese the unfaithful light torches, venerate trees, fountains and rocks and the bishop responsible neglects to destroy those sanctuaries, he commits a sacrilege. The landlord or the administrator is to be issued a caution; if he does not comply he will be excommunicated.” It was difficult to charge fountains and rocks but there was a chance with trees. Many a devoted missionary became a lumberjack from conviction.

The Battle of the Teutoburg Forest. Drawing of Crown Prince Frederick III. Clearly visible are the oaks under which the Prussian Prince let the battle take place.

Of course, the Germanic peoples had their sacred groves, too. If Tacitus (II, 12) is to believed Arminius concentrated his troops in a grove sacred to Thor before he defeated Varus. The booty was stored in a sacred grove as well. The Annals tell us that Germanicus visited the battle field in the Teutoburg Forest in A. D. 15 and came across the sculls of the soldiers killed in battle hanging from the trees.

Hence, for the Romans the oak was connected with the rebellious peoples of the North. Resistance was something Rome could not tolerate. The renitent comrades-in-arms of the independence movement had to be crushed. Those who were wiped out were the “oak knowledgeable”, the druids. The Romans left the oaks but the veneration was not quite the same after the victory of Christianity. The Christians preferred the martyrs’ palm; the oak became a nuisance to the rigid church fathers. The places where the believers were close to the idyllic vegetation deities had to disappear. That was a matter for the boss. The Second Council of Arles (A. D. 452) issued the following edict: “When in a diocese the unfaithful light torches, venerate trees, fountains and rocks and the bishop responsible neglects to destroy those sanctuaries, he commits a sacrilege. The landlord or the administrator is to be issued a caution; if he does not comply he will be excommunicated.” It was difficult to charge fountains and rocks but there was a chance with trees. Many a devoted missionary became a lumberjack from conviction.

Boniface felling the oak of Thor. Copperplate drawing by Bernhard Rode, 1781.

The “Apostle of the Germans”, Saint Boniface, to name only one example, felled in autumn 723 a huge oak with ostentation. His victim was consecrated to Thor and stood near the Hessian city of Geismar. A number of Chatti to be converted had gathered around the venerated tree in the hope that their god would not let go this humiliation unpunished and strike the churchman dead with a lightning. As a matter of fact, Thor did not defend himself, and his oak was split into four which Boniface took to build a chapel consecrated to Saint Peter. (Instead of lightning, some Germans unwilling to be converted chopped the head of the oak malefactor.)

When Christianity prevailed the sacred trees were made profane. Some local remains of a tree veneration namely in popular belief – Joan of Arc, for example, was condemned amongst other things because of her alleged unnatural veneration of a tree – and the epiphany of Virgin Mary especially in oaks (in Portugese Fatima, for example) notwithstanding, in Medieval Times the oak served rather practical purposes, as for pig fattening or as shade-giver in trials.

Famous was the oak of Saint Louis, King of France between 1226 and 1237 who, according to legend, took exemplary care of jurisdiction especially for plain people. Wherever he was asked to judge in an argument, he looked for the nearest oak, sat under it, called all involved parties and decided a (naturally fair) verdict.

Portrait of Francesco Petrarch.

The oak as a symbol was rediscovered in the Renaissance. A new sentiment of nature had emerged when Petrarch climbed to the top of the Mont Ventoux at Carpentras in 1336. He wanted to experience similar feelings like Philip V of Macedon on the Haemos as the devoted mountaineer had read in Livy. What had begun as an imitation of the ancient protagonist soon developed a dynamic of its own. Poets and thinkers apprehended nature in a novel sense, not practically oriented. They looked for the example, tried to interpret, to find the microcosm in the macrocosm, i.e. an image of the entire world in a single plant.

The characteristics once alleged to the oak were remembered. One praised its strength and used it as symbol for it in emblemata, pictures that intend to verify a common truth with an epigram with an example taken from nature.

This image depicting a very early Modern equalisation of the oak and the German Empire was accompanied by the following epigram: Was sehr fest ist kann nit bewegt werden. / Ob schon von Est das vngstümm Meer / Mit seinen Wellen brausset her / Vnd du wütrich Türck von auffgang / Den an der Donaw wohnt machst bang, / So wirstu doch vermögen nicht / Ein schaden zuthun, dieweil verficht / Keyser Carle mit gewaltiger Hand / Vnd mit Heeres macht Leut vnd Land. / Gleich also wie ein Eychbaum bleibt / Fest vnbewegt stehn, ob schon treibt / Hinweg die leichte Bletter dürr / Der grosse starcke Wind vnghürt. – King Charles, fighting the Turks, is compared here with an oak, solid and unconquerable.

In that context, the oak was able to become a symbol of the state as well. The epigram’s inventors wanted to show with an image of the oak the powerful, impregnable tang of the united state that could not be defeated by a tempest from outside but from time or discord only. It is interesting that the oak was regarded a symbol of the German Empire as early as Baroque Times.

Johann Heinrich Voß. Sepia drawing by J. N. Peroux.

It was no wonder then that six students met in the city of Göttingen in a moonlit night under an oak to found a covenant on September 12th, 1772. Johann Heinrich Voß had the idea, translator of Homer’s works and quite familiar with the ancient literary sources. He knew about the connection between oaks, Germanic people and the fight against the Romans. The Roman, however, was not to be found in Italy but in France, the origin of civilization some intellectuals with national pride thought to suppress the German. The aim of the covenant was to establish a counterweight to that alien civilization and to create a distinct German poetry. Voß wrote about that in a letter: “We clad the hats with oak leaves, laid them under the tree, grabbed each other’s hands danced around the stock, called the moon and the stars as witnesses of our covenant and promised each other eternal friendship.” Amongst those who felt a close connection to that movement were such well-known poets as Ludwig Hölty (Üb immer Treu und Redlichkeit), Gottfried August Bürger (Lenore fuhr ums Morgenrot empor aus schweren Träumen) and Matthias Claudius (Der Mond ist aufgegangen). Following their spiritual father Klopstock, they spread the picture of the oak as requisite for national sentiment in countless works. Arminius embraces Thusnelda in the shade of an oak or intends to die in the shade of Thors’ oak, the bard strides under oak leaves shading his burning forehead, Christian Friedrich Schubart poetized in 1786: Freiheit! Freiheit! hörst du tönen / Aus dem alten Eichenhain. / Wandelst bald mit Teutschlands Söhnen / Wieder an dem freien Main. // Freiheit! Gottes größter Segen! / Freiheit, ach wann wandelst du / Mir Bestürmten auch entgegen? / Bringst mir wieder Seelenruh? (Liberty, liberty! That you hear from the old oak holt. Soon you will be strolling with Germany’s sons again at the free Main River. Liberty! God’s biggest blessing! Liberty, when do you come to me, perturbed? When will you bring me peace of mind?)

Liberty, Germany and the German oaks – that triumvirate unexpectedly gained enormous political topicality by the fact that bigger and bigger parts of the country were controlled by the Frenchmen. Foreign rule aggrieved the German country like the Roman in their days and hence all German Hermanns dreamed about expelling the tyrants. Of course, that was bound to happen under German oaks. The Napoleonic Wars made sure that the patriotic national poetry raged itself out. Countless testimonies can be found of how every German poet, thinker and, most of all, politician – including every halfway ambitious national hero – praises German oaks, plants them or orders them for grave decoration. That became fashion even at the imperial court. Frederick William III donated the Iron Cross sheeted with three oak leaves on March 10th, 1813, the birthday of his queen Louise who had already died. The draft was made by him personally.

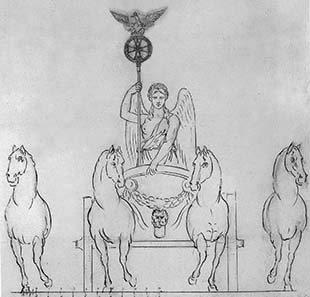

By the victory sign designed in 1814 the goddess of peace becomes Victoria announcing the victory over the French.

It was him as well who, in the middle of May the following year, awarded Karl Friedrich von Schinkel the contract for designing a special victory sign for the quadriga of the Brandenburg Gate just reclaimed from Paris. Schinkel described the sign of the national victory as follows: “The idea of the design to be executed was to equip the Victoria with the Prussian banner instead of the usual palladium. That Prussian banner consists of an oak wreath encompassing the Iron Cross above which the Prussian eagle seems to ascend with spread vans.”

Prussia. Frederick William III, 1797-1840. Taler, Berlin, 1813. Jaeger 33. From auction sale Münzen und Medaillen AG 91 (2001), 117.

In the enthusiasm following the victory the oak wreath even found entrance into the Prussian coinage for a short time.

Prussia. Frederick William III, 1797-1840. Taler, Berlin, 1813. Jaeger 37. From auction sale Münzen und Medaillen AG 91 (2001), 118.

Admittedly, it disappeared on the taler as early as 1816, on the 4 groschen in 1818. Only long after the bourgeois revolution of 1848 the oak wreath occasionally showed up on Prussian coins again.

What are we to make of this gap on coinage? Why did not the King of Prussia want to have anything to do anymore with the oak so dearly praised before? The answer is simple – the pan-German oak wreath did not fit into daily politics anymore. The days of German nationalism were gone, and the particularism reared its head again. Prussia wanted to be Prussia not some part of Germany. Most of all, the oak wreath did not suit the restrictive Prussian policy of suppression of all democratic movements after the Carlsbad Decrees of 1819.

After all, the oak wreath was, from Antiquity onwards, a symbol not reserved for Germany but involving another connotation. The Greeks honoured citizens of outstanding merit with oak wreaths made of gold. The Romans as well cultivated that custom. Their “corona civica“, i.e. the citizen’s crown of oak leaves, played an even more important role. It was only bestowed on the one who had rescued a Roman citizen from a life-threatening danger. The honoured person was allowed to wear the wreath all times from then on and was granted tax exemption together with his father and grandfather. Everybody, including the senators, honoured him by ascending from the seat when he appeared at the games.

Augustus, 27 B. C. – A. D. 14. Denarius, Caesaraugusta, 19-18. Head with oak wreath l. Rev. laurel tree. From auction sale MMAG 93 (2003), 83.

That oak wreath became a political symbol when it was bestowed on Augustus , together with many other honorary titles and some decisive instruments of power, on January 13th, 27 B. C. Of course, all honours the senate bestowed on him had been carefully chosen by Augustus and his personnel in regard to their effect on the public. When Augustus chose the golden oak wreath he stressed his civil element, his benefits for Rome (although these benefits had been for decades that he engaged Romans against Romans).

Amsterdam. Medal 1648. Holy Roman Emperor Maximilian granted the city of Amsterdam their privileges in 1488. Scenery encompassed by oak wreath. Rev. Philipp IV sealed the peace with the seven provinces. Scenery encompassed by oak wreath.

In the Renaissance, the oak wreath was rediscovered as a symbol of honour for men who had taken a stand for the citizens’ rights. Anyone using the oak crown from then on, wanted to stress his closeness to citizens.

France. Louis-Philippe I, 1830-1848. 5 Francs 1848, Straßburg. Dav. 91. From auction sale MMAG 91 (2001), 686.

The best example for that is the coinage of Louis-Philippe, the French king, who rose to power thanks to the July Revolution of 1830. After Charles X of the House of Bourbon had discredited himself due to his restrictive policy, Louis-Philippe sought a compromise between liberal and conservative powers. He expressed his objective to selfless serve the state with the head gear he chose for his coin likeness, an oak wreath. Apart from that, he did not continue to call himself King of France but – like the executed Louis XVI did by order of the National Convention – Kind of the French.

Henceforth, the oak wreath was regarded a political statement readily used in the German Empire by those who wanted to stress their national views and their enthusiasm for democracy.

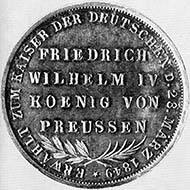

Frankfurt. Medal on the election of Frederick William IV as “Emperor of the Germans”. Diameter 45 mm.

Naturally, the liberal revolution of 1848 resulted in a new blossom of oak depictions. A medal on the election of Frederick William IV as Emperor of the Germans shows Germania resting on a stub of an oak that symbolises the perished first Empire of the German Nation. A small young shoot sprouting from the dead tree stands for the second German Empire that was not going to come into being (yet). Frederick William IV rejected the honour he was granted. He did not want to have a crown “baked from dirt and loam“.

It goes beyond the scope of this article to list every occurrence of the oak on German coins. From 1848 onwards, people regarded the oak as a steady symbol of pan-Germany which could be used again and again to evoke national elation.

Unity and justice and freedom were evoked by the oak on the 5 Mark coin of the Weimar Republic. Very different ideals were fostered by the National Socialists who crowned the victors of the Olympian Games of 1936 with oak leaves and presented them with an additional small oak in a pot. The oak could be used and misused for everything.

FRG. 50 Pfennig 1949, Munich.

It may be used as a fresh symbol when the reconstruction had to be undertaken after the German defeat of 1945. The woman with a headscarf planting a young shoot of an oak that could grow to a massive German oak again became a symbol for the reconstruction of Germany.

Hence, the small and unspectacular oak branch on the German 1, 2 and 5 Cent coins is a reminder of former greatness, hopes and missed chances. It is a good thing that it had been adopted for the new Euro coins. No other plant, no building, no ship would be better suited to symbolise German’s history of growing together to a democratic nations of citizens than the small and modest oak branch.