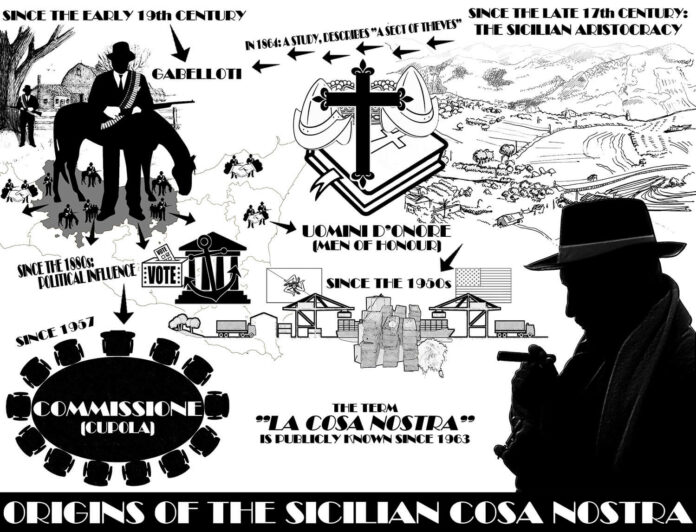

With the unification of Italy, a new phenomenon emerged in rural Sicily: the mafia. In the 18th century, noble landowners in South Italy had started to move to their comfortable residences in the cities. This triggered a significant change in traditional structures: the absent families gradually lost control over their huge estates in the country – the latifundia. The new lords of the estates were the “gabellotti”, tenants who sublet the land to peasant families at horrendous prices, got paid in money or in kind, and gave part of the proceeds to the actual land owners.

These gabellotti did not only exploit the peasantry but also put pressure on landowners: they offered lords, barons or counts protection from robbers, rustlers and rebellious peasants. In case the noble lords did not want this protection, the gabellotti gave substance to their offer: by cutting olive trees, vines and killing cattle.

To make sure the estates were actually protected, the gabellotti needed helpers. Piece by piece, a criminal network emerged revolving around the core business of extortion.

With the gradual expansion of voting rights, the mafia also penetrated the political world. Immediately after the founding of the state, census suffrage only allowed half a million man to give their vote: the electoral census amounted to 40 lire – a fortune that only the mostly aristocratic and conservative upper class was able to hold. However, by 1913, suffrage was extended to almost all adult male Italians. This meant that many conservative deputies in Rome feared losing their mandate to a social revolutionary opponent. This was remedied by the mafia: there were enough people who voted conservative deputies among Sicily’s rural population – because voting the right people equalled protection from reprisals. By the way, the relationship between “cliens” and “patronus” in ancient Rome, which was based on protection and duties, worked quite similar: the “cliens”, a Roman citizen who was free by law but economically and socially dependent, accepted protection from a “patronus”. The patronus represented him in dealing with the state, in return, the cliens must perform certain services for the patronus and support him with his vote in the magistrate elections. The political life of ancient Rome was decisively determined by these relationships.

In such a way, the mafia extended its control over Sicily’s rural population. In return, the deputies that were elected thanks to the help of the mafia prevented anti-mafia laws from being adopted by parliament. Thus, the connection between Roman politics and the mafia grew stronger and stronger until the influence of the Honoured Society was no longer limited to the south of the country. As a result, the economic and social modernisation of Italy was severely hampered by crime interfering with politics.

We can hardly understand what a census of 40 lire meant at the time. Even at the end of the 19th century, most Italians could only dream of such an amount of money. Many families lived off agriculture and led a life in extreme poverty. Compared to Great Britain, France or Germany, Italy’s industrialisation had only just begun – and was limited to northern Italy. In the north there was electricity as well as transportation and sales opportunities – an infrastructure that did not exist in the south. But even agriculture itself was hardly mechanized, and many families could barely live on the land they sat on. In addition, there was a huge crowd of landless seasonal workers who toiled for a pittance on the large latifundia in the south. Moreover, Italians were the most heavily taxed people of Europe in around 1880. The war cost the young state a lot of money and the colonial expansion policy also swallowed up vast sums.

In 1898, a poor harvest led to a massive increase in the price of bread: it rose from 50 to 60 centesimi per kilo, in some places even up to 75 centesimi. This triggered a wave of revolutionary unrest that spread rapidly from South Italy to the rest of the country and culminated in a full-blown uprising in Lombardy. After bloody battles, the army was able to put down the revolutionaries. The assassination of Umberto I (1878-1900) in 1900 was the last echo of these bitter domestic struggles.

In the next episode, we will see how inflation drives up the cost of living to incredible heights and puts one man at the top of the country after World War One: Benito Mussolini.

Here you can find all parts of the series “From Lira to Euro. Italy’s History in Coins”.