The city of Hamburg had a problem. All ships that intended to use its port and, in order to do so, went up the Elbe River, passed territories the Danish king made a claim to. He was not only King of Denmark but, being Duke of Schleswig and Holstein, also strongest power in the Lower Saxon Circle.

Christian IV of Denmark, c.1611-1616. Source: Wikicommons.

When Christian IV assumed power in Denmark in 1588, he considered northern Germany most suitable to expand into. The religious wars of the Thirty Years’ War opened a chance for him to increase his influence at the expense of the imperial central power: in 1625, he pushed his election as head of the Lower Saxon Circle through. Of course, Christian didn’t feel obliged to the empire but solely to his own agenda which he sold as a concern of the Protestants. His army was funded by The Hague Alliance, hence the two (Protestant) trading nations of England and the Netherlands. The plan was to get the big trading and harbor cities in the north under Danish (or Protestant, respectively) control. Verden and Nienburg were the first victims. When they were taken, the emperor sent his two commanders Tilly and Wallenstein with large troops north. Christian’s army was beaten in the Battle of Lutter. The Danish king was forced to sign the Treaty of Lübeck in 1629. Hence, he backed out of the war for the time being.

Ferdinand II. Emperor of the Holy Roman Empire, c.1635. Source: Wikicommons.

Hamburg had been given a reward, shortly before the Treaty was signed, in order to tie the Protestant city to the Catholic emperor.

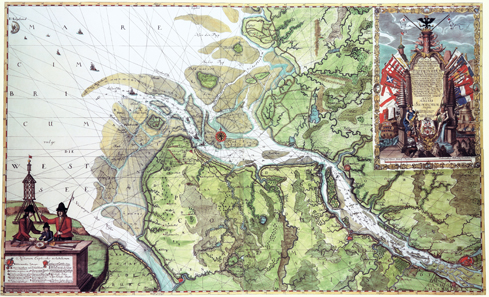

Map of the mouth of the Elbe River from 1721 by Samuel Gottlieb Zimmermann and Otto Hasenbanck. Source: Wikipedia.

On 3rd June 1628, Ferdinand III granted the Grand Privilege of the Elbe that entitled the city – despite all claims of the Danish king – full control over the lower Elbe. That was the best reason for the city, which depended on trade ships making use of that inexpensive tributary to the sea, to remain loyal to the empire. For Christian IV, in contrast, that privilege was a trench on his rights as Duke of Holstein. Naturally, he wasn’t willing to accept that in the long run. He wanted a customs established that would enable him to siphon off a part of Hamburg’s revenues. 1633 – Axel Oxenstierna had just powerfully united the Protestants in the Heilbronn League – the emperor granted the Dane customs on the Elbe for the period of four years. On 6th January 1636 – the Protestant imperial estates had taken sides again with the emperor after the Peace of Prague – Ferdinand II refused renewal of the customs regulation. Hence, Hamburg possessed the full Privilege of the Elbe and the access to the free sea.

The city of Hamburg thought that was the final end to all quarrels. To celebrate the victory, Sebastian Dadler was engaged to create a medal. Its reverse programmatically repeats the inscription that can still be viewed at the portal of the Hamburg town hall: LIBERTATEM QVAM PEPERERE MAIORES STUDEAT SERVARE POSTERITAS (= The liberty the elders have achieved posterity may preserve.).

Hamburg. Silver medal from 1636 by Sebastian Dadler. 79 mm; 127.11 g. Gaed. 1553. Maué 39. Very rare. Extremely fine to FDC. From auction sale Künker 242 (20th November 2013), nr. 3527. Estimate: 20,000 euros.

The obverse shows a motif that had been hitherto used in a similar form in emblems only: a colossus whose legs straddle the entrance to the Hamburg harbor. Until that day, that subject had been associated with the motto ‘only the great pleases’. Dadler, however, used the motif to illustrate the size of Hamburg which – and that was the comparison – matched up with ancient harbor city of Rhodes. While the Colossus of Rhodes was an image of the god Helios, Hamburg was given a Hanseatic variant: Mercury as embodiment of the trade, wearing a winged cap and winged shoes, a staff with entwined snakes and an olive branch as symbol of peace. To avoid any mistaken identity, the god carries a plate around his neck depicting the city’s coat of arms. Cornucopiae on both sides embody the affluence both of land and sea. Two women can be seen behind Mercury: one is standing on land, holding a spade, between bunches of goods and barrels; the other one is standing on a barge decorated with the globe of the earth, sailing the Elbe River. In the background a harbor is depicted, protected by a fortress, as well a ship under full sail.

The medal’s reverse.

The medal’s reverse is remarkable. For the subject Dadler drew on a map that was to be published a few years later, in 1644. Dadler most probably had seen early drafts of that marvel. He represents that map in such detail that Gerd Hatz was able to show in 1989 that an engraving by Arnt Pitersen, published in 1944, must have been the model.

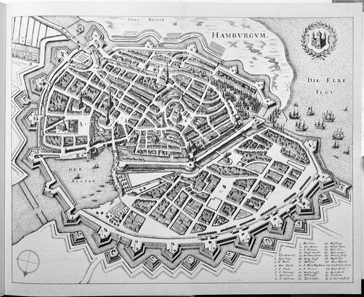

Matthäus Merian, city map of Hamburg, before 1653. Source: Wikipedia.

In 1636, Hamburg was sure on a rosy future. The Privilege of the Elbe had been granted and soon the revenues would flow. But more than a century was to pass until the struggle for Hamburg’s autonomy from Holstein was finally decided – a struggle that was rekindled again and again by the Elbe customs. Only with the Treaty of Gottorp from 1768, Denmark acknowledged the imperial immediacy of the Hanseatic city officially.

You can find this medal in this Künker auction.

And this is the auction preview of the upcoming Künker sale.