Have you read Umberto Eco’s picaresque novel “Baudolino”? From the perspective of modern skepticism, it tells the story of how the remains of the Three Magi ended up in Cologne: In 1158, in besieged Milan, Baudolino, young protégé of Holy Roman Emperor Frederick I (“Barbarossa”), finds some bones in the ruins of the Basilica of Sant’Eustorgio. He decks them out with splendid fabrics and shows them to Rainald of Dassel, Archbishop of Cologne and Archchancellor of Italy, who is accompanying Frederick I on his campaign against Milan and immediately recognizes the potential of these bones. As visible symbol of heavenly grace, he brings them to the Cologne Cathedral and thus makes Cologne an important place of pilgrimage.

Bracteate, Saalfeld. The Archbishop of Cologne, Rainald of Dassel, with crozier and miter, next to the abbot of Saalfeld. Extremely fine. Estimate: 2,000 euros. From Künker auction 313 (October 9, 2018), no. 3521.

Is that really how it happened? We do not know. But it is a fact that, on June 9, 1164, Frederick I issued a certificate conferring the ownership of the relics of the Three Magi to the Archbishop of Cologne. The latter had the remains ceremoniously transferred to the Cologne Cathedral on July 23, 1164.

The Shrine of the Three Kings in the Cologne Cathedral, made by the then highly famous goldsmith Nicholas of Verdun. Photo: Beckstet. CC-BY 3.0.

In medieval times, the possession of such a relic was a strong argument for the German king to be the only true emperor and thus of higher rank than all the other European rulers. After all, the Three Magi were the first rulers to pay devotion to the Christ Child. The fact that Frederick I owned their relics underlined heaven’s appreciation for him.

Rainald of Dassel. Photo: Elya, edited by MagentaGreen. CC-BY 4.0.

And of course, the possession of those relics brought loads of pilgrims to Cologne, too. The desire to provide the pilgrims with a possibility to walk around the Shrine of the Three Kings was probably one of the main reasons for building the new Gothic Cologne Cathedral.

Diocese of Cologne. 1688 Vacancy of the See. Reichstaler 1688. Very rare. Extremely fine. 4,000 euros. From Künker auction 313 (October 9, 2018), no. 3634.

The people of Cologne were proud to have the Three Magi in their city. Hence, it is no surprise that they repeatedly put their image on their coins.

City of Cologne. Ducat 1753. Nearly extremely fine. Estimate: 1,000 euros. From Künker auction 313 (October 9, 2018), no. 3766.

What’s more, they also added their three crowns to the city’s coat of arms.

But what is that in the lower half of the coat of arms? Some kind of flames. These, too, represent fellow holy citizens whose protection the people of Cologne put their trust in: Saint Ursula and her 11,000 companions.

Ursula and Aetherius on their pilgrimage reach Rome and Pope Cyriacus. This part of the legend only became established during the 12th century. Vittorio Carpaccio, The Legend of Saint Ursula. Galleria dell’Academia / Venice. CC-BY 4.0

According to the legend, Saint Ursula was the daughter of the king of Brittany, and the pagan Prince Aetherius wanted to marry her. Yet, Ursula had pledged maidenhood. In a dream, she received the instruction to ask for a hold time of three years, allowing her to stay true to her vow. The three years were granted, and after they were over she sailed to Cologne with 11,000 companions. But Cologne at that time was besieged by pagans, who martyred Ursula and her companions.

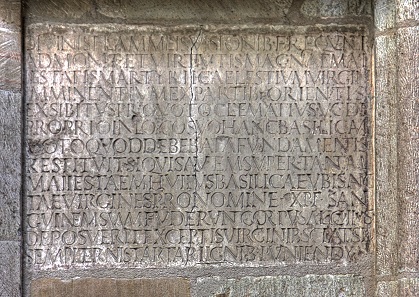

The Clematius Inscription. Photo: © Raimond Spekking / CC BY-SA 4.0 (via Wikimedia Commons).

This legend can be retraced all the way back to a Latin stone inscription from the 4th or 5th century, telling of a certain Clematius who built a church for the venerable martyr virgins.

The inscription became topical in 1106, when, during the extension of the city wall, a Roman cemetery was found, bearing loads of bones which naturally had to be relics (they were big sellers at the time). The cemetery was named Ager Ursulanus (=Ursula’s field). Somehow, a few of the bone fragments found there ended up with Saint Elisabeth of Schönau, a great mystic who had detailed visions about the martyrdom of Ursula and her 11,000 companions. Her brother Egbert put everything in writing in 1156/7, producing “The Book of Revelations about the Sacred Company of the Virgins of Cologne”. It contained names for many of Saint Ursula’s companions – and strongly fueled demand for the relics from Cologne.

Other mystics, too, felt the need to embellish the story. Hence, Saint Hermann Joseph of Steinfeld in his hymn on Saint Ursula was already able to cite 9,816 virgins, by name or anonymously.

City of Cologne. Gold strike at 4 gold florins from the dies of the Dreikönigstaler [Three Magi taler], no year (around 1620). Extremely rare. Very fine. Estimate: 50,000 euros. From Künker auction 313 (October 9, 2018), No. 3724.

Our gold strike from the Bankhaus Sal. Oppenheim Collection shows the key scene of Saint Ursula’s legend, as it has been established since the 13th century. In the center of a boat going up the river Rhine towards Cologne, we see Saint Ursula, wearing a crown. To her left, elaborately dressed, is Prince Aetherius. He had promised to get baptized after the three years’ waiting period. Together with his bride-to-be, he had gone on a pilgrimage to Rome, where the two of them were joined by Pope Cyriacus (not historically verified). We see him with a tiara and a processional cross to Saint Ursula’s right. The coin depicts the moment of the attack by the pagan besiegers of Cologne: While the prince protectively covers his body with his arms, the holy virgin is praying to God, supported by the brave pope who brings the Christian message to the land of the unbelievers.

A suitable message in the age of crusades. Bear in mind, in 1099, seven years before the Ager Ursulanus was “discovered”, Jerusalem had been captured during the First Crusade. But also a suitable message around 1620, at the beginning of the Thirty Years’ War, when the Cologne series of Dreikönigstaler was minted. At that time, the exponents of the Counter-Reformation took up arms in order to militarily fight the new Protestant way of thinking which supposedly did not need any saints. Of course, the reformists were also met with mental weapons, with the remains of 11,000 virgins that had bravely joined the battle against unbelief.

The “Golden Chamber” of Saint Ursula in Cologne. Photo: Davidh820 CC-BY 4.0.

Ursula and her support were considered essential in the battle against the Lutheran faith, which is shown by the fact that Emperor Ferdinand II, together with the Archbishop of Cologne, began the canonization of Saint Ursula’s great mystic, Hermann Joseph of Steinfeld. And in 1643, the imperial court counselor Johann Krane and his wife had the “Golden Chamber” for keeping the relics of the 11,000 virgins, which already existed at the time, erected in its present form.

Due to this wealth of relics, medieval Cologne had become a new Rome. And of course, both the people of Cologne and their bishop were ready to fight for their saints. And not only in the 17th century. During the French occupation, the relics of the Three Magi were evacuated to the free town of Deutz. Only after Napoleon’s Concordat with the Catholic Church, they returned to their usual place on January 6, 1804.

You can find more coins and medals from Cologne in the Bankhaus Sal. Oppenheim Collection entitled “Geprägte Kölner Geschichte” [Minted History of Cologne]. The full auction catalog is available online.

CoinsWeekly published an auction preview of all five Künker sales of October 2018, too.